Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCAMPAIGN FINANCE: How to Win an Oscar—or Go Broke Trying

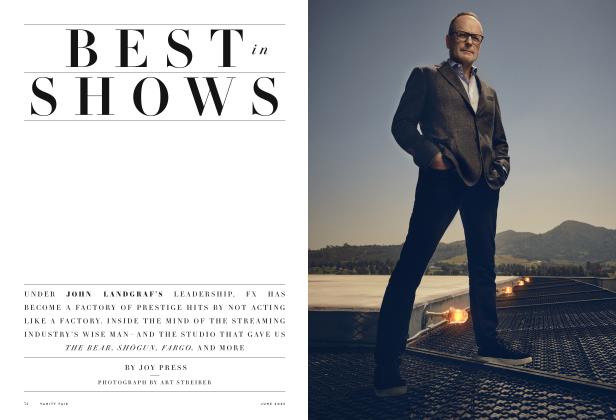

Awards season, an annual circus of consultants and events, is awash in money. Nearly everyone involved seems to tolerate this at best. So why does Hollywood keep doing it? JOY PRESS looks for answers

JOY PRESS

A crowd swarms outside the grand Hotel Excelsior, stretching all the way down to the Palazzo del Cinema, where Guillermo del Toro's Frankenstein is about to have its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival. Inside the hotel, del Toro sits on a low chair engulfed by well-wishers who place drinks in front of him like sacred offerings. Hours later— after the movie has screened, receiving a standing ovation that lasts more than 13 minutes—I spot the filmmaker once again. Leaning heavily on a cane, del Toro makes his way up the dock, where a water taxi will whisk him away as festival attendees cheer. Later that night I overhear someone say, "Frankenstein has officially entered the awards chat."

That's one of the very reasons studios send their movies to Venice, where a single ride on a private water taxi can cost as much as a meal at Le Bernardin. It's the quickest way to put your movie on the radar of Academy Awards voters. Frankenstein was just one of Netflix's Oscar hopes to premiere there in 2025, alongwithNoah Baumbach's Jay Kelly and Kathryn Bigelow's A House of Dynamite. But other streamers and studios were just as eager to join. New movies from auteurs Yorgos Lanthimos, Luca Guadagnino, and Park Chan-wook also launched there this year, and superstars like Juha Roberts, Jude Law, Colman Domingo, and Cate Blanchett all walked the red carpet.

Festivals like Venice are a highly effective way of reaching the Oscar electorate, given that just over 20 percent of Academy members are now located outside the United States. So studios seeking gold statuettes send their contenders on a grueling marathon of global film festivals: After the Floating City, there's Toronto, Sao Paulo, and Stockholm.

"You feel like a bit of a hustler," the director of an Oscar-winning film tells me. "You feel weirdly exposed doing constant interviews and events where you are trying to galvanize people behind the project." He speaks longingly of the early days of the Academy Awards, when "you just showed up on the night and had a few martinis. But it's evolved into this huge Oscar industrial complex. It's mind-boggling...and a little soul-destroying."

For an actor like Channing Tatum, it's also nightmare fodder. He describes the Cannes Film Festival as "entering the Colosseum with your art piece. It's like a gladiator going in, and you can die."

Awards strategists act as unofficial tour guides through this prestige circus, helping studios plan complex campaigns, covertly shape the media narrative about a movie, and usher talent through the awards season gauntlet. Harvey Weinsteinweaponized "for your consideration" campaigns back in the 1990s at Miramax, which became a training ground for many of today's awards gurus. In 2025, as the movie industry struggles, the quest for Oscars has only intensified. So has the price tag, inspiring one of Hollywood's favorite guessing games: Did one studio really spend $60 million on awards hype for a single film in a recent season, as some competitors have whispered? There's no transparency, because the first rule of awards campaigning is do not talk about awards campaigning.

Occasionally someone says it out loud, though, like Neon's Tom Quinn, who owned up to forking out $ 18 million on the marketing, distribution, and awards campaign for last year's Oscar winner, Anora—triple the budget of the actual movie. That was after the distributor spent what was said to be $20 million on Neon's first best picture winner, Parasite. I'm told $20 million is a pretty standard awards budget for major studios these days, though indies can make do with far less. Rarely does anyone want to admit to throwing wads of money at a prize, but campaign expenses might include buying an ad on the front cover of a trade magazine like Variety, as A Star Is Born did; throwing an elaborate Victorian-style fair complete with hot-air balloons, as Amazon did for The Aeronauts; sending select voters signed sheet music for Billie Eilish's theme song from MGM's James Bond movie No Time to Die; or flying in the cast to surprise guests at a New York screening, as Warner Bros, did for One Battle After Another. Last year, days before the final Academy Awards voting deadline, Oscar nominees Bradley Cooper and Carey Mulligan even appeared at a Lincoln Center program during which Cooper's conducting teacher for Maestro led members of the New York Philharmonic through music from the film.

Streamers helped push up budgets in recent years. "They need to differentiate themselves, and also they need to get high-caliber talent to come to the studio," says one awards space publicist who's worked for both streamers and traditional studios. But the idea that spending the most money will nab votes—well, that just results in the world's biggest eye roll.

"If you could buy a best picture Oscar, Netflixwould have won," the publicist continues. The streamer has come close, with a best picture nominee every year since 2018, but so far the big prize has eluded it despite substantial awards budgets. "The one thing that we've truly learned over the years is that you cannot tell people how to vote, no matter how much money you spend."

In fact, says veteran awards strategist Tony Angellotti, "I'm confident on a number of occasions regarding previous nominees and wins, the team I worked for spent less than the competition." But like other strategists I speak to, he describes a bespoke process that's different for every movie. "When you have a film on a roll, the budget necessarily expands because the campaign beast needs to be fed by event participations, more advertising, more screenings, etc. The range is all over the place, depending upon the pockets of the distributor. It can be like trying to pin a tail on a donkey blindfolded, figuring out what a budget might be early on."

A massive vibe shift occurred in recent years, as the Academy's post#OscarsSoWhite push for a more diverse membership led to a voting body spread across the globe. It's as A Parasite opened the floodgates and the whole world rushed in: Instead of American studios competing only with one another for recognition, they are now sparring with all of international cinema.

"The Academy once was around 6,000 people. Now we're close to 11,000," says publicist Lea Yardum, who's worked with best picture winners including Parasite and Anora. "They have different points of views. They speak different languages. So there are a lot of logistics that you have to conquer in the course of doing your day-to-day job." Rather than bringing the director and stars of a film to Los Angeles for two months, for instance, strategists now may send them off to far-flung locations to kiss babies and befriend local cinephiles.

"It's like Groundhog Day," says Maria Clemente, cofounder of awards strategy agency Take2. "You're doing the same thing over and over again, one day after another, but in different cities with different audiences." Her business partner, Antonio Gim6nez-Palazon, compares it to a political campaign. "You cannot just get away with just a big convention—you have to do grass roots and go where the voters are." By one estimate from Oscar pundit Steve Pond, it could take fewer than 1,000 top votes to guarantee a best picture nomination, and just over 200 for best actor, so it's worthwhile to leave no vote unturned. Gim6nez-Palazon says turnout is generally stronger and more fervent in international cities than Los Angeles, where jaded industry insiders get bombarded by invitations to events. And when an overseas film or actor is nominated, it becomes a matter of national pride: "The Oscars, it's like a gold medal in the Olympics," he says, remembering mass celebrations in the streets of Brazil when I'm Still Here won last year.

One high-profile strategist was pleasantly surprised by recent screenings in Europe. "I was like, 'Oh, this is different here—they don't go all out on the food and drinks like they do in the US. ' These people actually come to watch a movie. " It's a far cry from one American event, where an Academy member approached her. "He pointed his finger in my face and complained: 'You're not serving food at your screenings. ' I stood there for a moment and then I said, 'Why would I serve foodwhen everyone in that movie dies? You should really get in your car and think about what happened in that movie.' "

In the nonfiction scene, creative thinking was already essential. "We don't have the budgets, so we have to be frugal and nimble," says Suncatcher Productions founder Annalisa Shoemaker, who distributed the Oscar-nominated documentary feature To Kill a Tiger. Dev Patel and Mindy Kaling came on board as executive producers, using their platforms to promote the project. Having previously worked at Focus Features and Amazon Studios, Shoemaker says, "Iwas from the studio mindset of lots of money is what you need. This experience really made me rethink it. What really matters here? What are we doing?"

The Academy has attempted to reform the campaign process over the years to rein in the feeding frenzy. (The current rules forbid "sit-down meals" at screenings and the serving of any free food or beverage after nominations have been announced.) It also bans disparaging social media posts. Nearly everyone I spoke to believed that "dirty tricks"—negative narratives that suddenly materialize at a key point in the Oscars race, assumed to be planted by a competing strategist—have waned. Still, it's hard to know if smears or self-owns were at work last year, with the timely resurfacing of Emilia Pérez star Karla Sofia Gascon's offensive social media posts and the late-breaking revelation of an AI speech tool being used in The Brutalist.

Despite these potential land mines, awards season remains central to Hollywood—even more important than ever in this unstable moment. That's especially true for the talent. "Getting the cachet of winning an Oscar helps in negotiating new deals and just global recognition," says one longtime awards consultant.

Hence all those actors and directors trooping through an endless succession of festivals, screenings, talk shows, online interviews, and meet-and-greets. "I've been in situations where actors have really just committed to the campaign and appeared in everything, and it's had a definite effect," says the film director. If you don't go full bore into the awards circus and then you lose, you'll never know if you could have squeaked out a nominationwith a little charm offensive.

Just ask two-time Oscar winner Sean Penn, who is a potential contender again this year for his role in Paul Thomas Anderson's One Battle After Another. "Social discomfort" made him averse to participating in the awards race for many years. But when Mystic River was nominated in 2004, he felt he needed to support the film. "If you didn't go, you thought you'd be letting everyone down," he says. "You've saved some Percocet or something to get through a night. And then if you win, there's only one sensation you feel: It's relief. It's over."

—Additional reporting by

Rebecca Ford

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now