Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOLD MEDIA: The Autopsy Report

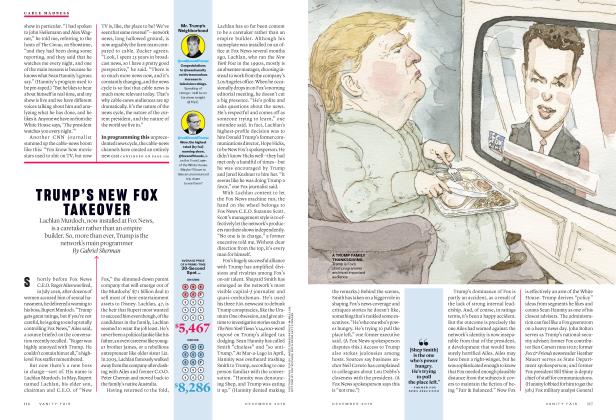

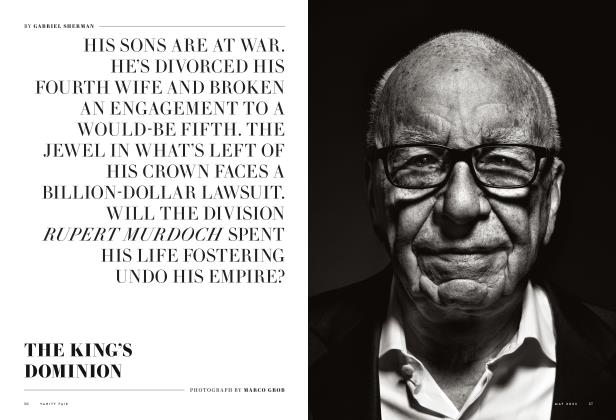

In an exclusive excerpt from his newbook, Bonfire of the Murdochs, GABRIEL SHERMAN dissects the collapse of a media dynasty

GABRIEL SHERMAN

For 70 years, Rupert Murdoch hid from confrontation. He fired his mentor by letter, divorced a wife by email, and used one child to fire another. But in a sterile Nevada courtroom in September 2024, the 93-year-old mogul's money and power couldn't protect him any longer. He would finally face his estranged children under oath.

In early December 2023, Rupert unilaterally altered the irrevocable family trust to install his son Lachlan as his successor. Murdoch's other adult children from his first two marriages—Prudence, Elisabeth, and James—sued to block the change. The lawsuit set up the final courtroom battle in a long-waged war to decide, once and for

all, who would control his empire following his death.

Discovery had been like an autopsy of a family's slow death. Depositions became an arena of psychological abuse. In one, Rupert's lawyer fired humiliating questions at James as Rupert looked on: Have you ever done anything successful on your own? Why were you too busy to say "Happy birthday" to your father when he turned 90? Does it strike you that, in your account, everything that goes wrong is always somebody else's fault? At one point, James noticed Rupert tapping on his phone and realized he was scripting the questions for the lawyer to ask. "How fucking twisted is that?" James later recalled.

For years, James had defended his father in public. At the Vanity Fair Oscar Party in 2018, he confronted a journalist who had written critically about the company. "You're just trying to make a buck off my old man!" he said as his wife, Kathryn, gently tapped his arm to calm him down. James could defend Rupert no longer.

Rupert crafted narratives in the shadows, but the courtroom would require him to do it in the open. He needed to prove that his decision to give his empire to Lachlan wasn't about politics, misogyny, or primogeniture. It was about money. Preserving Fox News's conservative voice was best for the business. The Nevada probate commissioner would allow Rupert to amend the trust if he acted in good faith to protect his children's financial interests. But James, Liz, and Prue—referred to in Rupert's court filings as the "Objecting Children"—had a crucial advantage: They simply needed to keep the status quo. Their lawyers prepared to argue that Rupert and Lachlan were disenfranchising them to further Rupert's dynastic and political project. If Rupert and Lachlan wanted them out of the trust, then they should pay a fair price for their shares. Anything else was stealing.

Facing the fight of his life, Rupert reached for his most reliable weapon: emotional manipulation.

Facing the fight of his life, Rupert reached for his most reliable weapon: emotional manipulation. When Prue's birthday arrived weeks before the trial, flowers appeared at her door. More brazenly, Rupert sent documents to James's lawyer with a handwritten note: "Dear James, Still time to talk? Love, Dad. PS.: Love to see my grandchildren one day." The message was vintage Rupert: personal appeal wrapped around a business proposition with a dash of guilt. None of the siblings took the bait. They had learned too much about their dad's methods to fall for his final charm offensive.

On the cold and gusty morning of September 17, Rupert arrived at the courthouse in a navy sweater under his dark suit, which he punctuated with a bright yellow tie. Photographs captured his wrinkled face, etched by deep grooves like a complex irrigation system. He climbed the courthouse steps with a pronounced stoop. It was the image of a man under siege.

Rupert's lawyer Adam Streisand had a difficult task ahead. The trial's opening day had not gone well for Rupert and Lachlan. Putting Rupert on the stand was a risk; he had a habit of stepping in it, especially when questioned. Years ago, Rupert's PR adviser blanched when Rupert blurted out during an interview that Muslims have an inbreeding problem because they marry their cousins. Streisand was one of the country's preeminent trust lawyers and well-positioned to shepherd Rupert through the most important testimony of his life. He previously litigated a lawsuit over the estate of William Randolph Hearst.

At first, Rupert stuck to the script. "I just felt sure, very certain that if these things weren't settled, there would be trouble," Rupert said, his voice faint but lucid. "If there's uncertainty about the management, the public will feel it, inside the company would feel it."

There was logic to his argument. But James had recruited a legal heavy hitter of his own to dismantle it: Gary Bornstein, the cohead of litigation at Cravath, Swaine & Moore. Under Bornstein's deft cross-examination, Rupert admitted that he changed the trust to protect his conservative legacy as much as the business. It would be a "disaster" for America if James convinced his sisters to depose Lachlan, Rupert said. Bornstein had Rupert cornered. "The solution to that problem of having [Liz and Prue] having to make a decision was for you to make the decision for them, correct?" he asked.

"Yes," Rupert replied.

In that single word, he put his self-serving misogyny on full view. When the session ended, Rupert left the courthouse and didn't return for the remainder of the trial. He told the judge he was sick, but James thought otherwise. "Itwas cowardice," he later said.

After each day in court, James, Prue, and Liz retired with their spouses to a friend's house in Lake Tahoe, about an hour away. They drank wine and reenacted memorable exchanges from the trial, but it was more than just debriefing—it was reconciliation. James and Liz were finally burying years of estrangement engineered by their father's manipulation during the phone hacking scandal. Even Liz and Prue, half sisters whose relationship had been punctuated by epic screaming fights, found common ground. The mood was cautiously optimistic, though the stakes were too high to truly relax.

The trial's third day belonged to the Objecting Children. This was the moment they had waited for their entire lives: the chance to tell their truth under oath and to have a judge rule their father had wronged them. They told a story of hurt and betrayal. Liz testified how "unbelievably close" she had been with her father, but now the relationship was "absent." James broke down crying when he talked about his mistreatment by his father and brother. "There have been a lot of hurtful things over the years," he said. "We worked together very closely for a long time. It's hard." As Lachlan stared back, James thought to himself: How had it come to this?

The siblings' emotions calcified during Streisand's pointed cross-examination. Streisand's questions were designed to reinforce the narrative Rupert's legal team had been pushing since depositions: James, Liz, and Prue were "white, privileged, multibillionaire trust-fund babies" scheming to advance their left-wing agenda at the cost of destroying their father's companies. Streisand sought to prove this by focusing on a secret meeting the three siblings held in a private room at Claridge's hotel on September 20,2023. In Streisand's telling, they had gathered in London to plan how they wouldfire LachlanuponRupert's death. "Is it customary for you when you have drinks with your siblings and dinner to book a hotel conference room?" Streisand asked Liz.

Liz admitted it wasn't, but the choice of venue wasn't evidence of a plot: They simply wanted privacy to discuss funeral planning for their father. According to depositions, the meeting had been encouraged by Liz's lawyer Mark Devereux, who conceived Project Bridge to prepare for Rupert's death. Devereux, a self-described Succession addict, was deeply troubledwhen he watched the episode that depicted the fictional mogul Logan Roy's sudden death and the kids' scramble to issue a public statement.

Streisand didn't buy it. He challenged James about the Claridge's summit. "Do you deny saying anything about suggesting that once you do have your agency, that you do something about getting your brother out?" Streisand asked.

"I do deny that," James said.

For much of the afternoon, James contained his trademark aggression. But late in the day, his patience with Streisand's questions expired. "It's garbage," he said. "They're making stuff up or believing things that they are being told to create some sort of boogeyman that is a justification for stealing stuff that they didn't want to buy."

Lachlan was the last to testify. The trial had unfolded like a microcosm of his life: He sat silently while others questioned his right to lead. He never asked to be his father's chosen son—it was his birthright, though at low moments it felt like a curse. No matter how much he achieved, critics questioned whether he was fit to stand in his father's shoes.

Lachlan got the kingdom; James, Liz, and Prue got their freedom.

The legal battle had crystallized Lachlan's anger at his siblings for never recognizing his business record. His several-million-dollar investment in the real estate listing service REA Group was now worth billions. He prudently stayed out of the streaming wars and instead invested modestly in the advertising-supported streamer Tubi. Despite this, his siblings never supported him publicly. In early 2023, Lachlan pleaded with Liz to issue a statement refuting a Financial Times article that said James would force him out upon Rupert's death. "This is terrible, and you have to say something," he told her. Liz declined. The betrayal stung. During James's testimony, when Streisand asked if he had ever supported Lachlan, James's answerwas brutal: "I don't believe so."

Even Rupert's absence from the courtroom felt like painful déja vu—just like the times Rupert had left Lachlan to fend for himself against the courtiers who wanted him gone. Itwas the Rupert way: His mother, Dame Elisabeth, had thrown Rupert into the water to teach him to swim. "I had to dog-paddle to the side, and I was screaming," Rupert once said. Now Lachlan was drowning alone.

But it was too late to get out of the pool. On the stand, Lachlan struggled. While his siblings gave hours of testimony about Rupert's psychological abuse, Lachlan was the lonely voice describing an attentive father who took him camping and generously made him and his siblings fantastically rich. "He gave the companies to us," he said. The real betrayal, Lachlan said, was his siblings' refusal to knock down the articles that said a coup was coming. "If Liz and Prue and James had come out at any point in this time, publicly, on the record, and said, 'This is false, Lachlan does not get fired the day Rupert dies, we are not a gang of three against him,' that would have stopped the stories," he testified. "It would have been a very simple, straight thing to do, and it would have been a decent thing too."

It was an emotionally resonant appeal but a legally ineffective one. Under cross-examination, Lachlan became flustered and evasive, like he was back in the boardroom struggling to debate James. He defended his father's warped philosophy that journalists should feed audienceswhat they want, even if what they want are lies. The nadir came when Lachlan admitted he had no evidence for his claim that James or his surrogates leaked stories about a coup. The trial had reduced Lachlan to a Fox News host. He was spreading conspiracies just like the network he controlled.

On Saturday, December 7, 2024one year to the day since Rupert launched the legal battle to amend the trust—commissioner Edmund Gorman issued his decision: Rupert lost. In a stinging rebuke, Gorman called Rupert's plan a "carefully crafted charade" to "permanently cement Lachlan Murdoch's executive roles...regardless of the impacts such control would have over the companies or the beneficiaries." This wasn't about business, Gorman said, itwas about a political legacy. Gorman ruled that Rupert wanted his companies to "continue to be alternative, conservative voices in [the] media after he dies. " To achieve this goal, Gorman said Rupert had violated the trust rules by trying to strip James, Liz, and Prue of their voting power to remove Lachlan after Rupert's death. Lachlan fared even worse. Gorman criticized his "lack of candor. ..on the witness stand." It was a humiliating coda.

Gorman's decision was a resounding victory for James, Liz, and Prue. They prevented Rupert from stripping them of their rights to determine the empire's future upon Rupert's death. In 2030 the trust expires, and the siblings are free to sell their shares to the highest bidder. "The effort was an attempt to stack the deck in Lachlan Murdoch's favor after Rupert Murdoch's passing so that his succession would be immutable," Gorman wrote. "The play might have worked; but an evidentiary hearing, like a showdown in a game of poker, is where gamesmanship collideswith the facts and at its conclusion, all the bluffs are called and the cards lie face up."

Even Rupert's effort to keep the most intimate details of his family's implosion secret failed: Someone leaked 3,000 pages of court records to The New York Times. In February 2025, the paper published a detailed account of the Nevada trust case.

About a month after the trial—before Gorman's decision was filed—James and his sisters sent Rupert a letter hoping to reconcile. "Thanksgiving and Christmas are upon us and the three of us wanted to reach out to you personally to say that we miss you and love you," they wrote. "We are asking you with love to find a way to put an end to this destructive judicial path so that we can have a chance to heal as a collaborative and loving family."

Rupert wrote back a couple of days later. He had read the children's trial testimony two times, "only to conclude that I was right": They were unfit to inherit the business. He said he only wanted to speak through lawyers going forward. "Much love, Dad."

Within a few weeks of the decision, Rupert and Lachlan had filed an appeal.

In the end, they settled. On September 8, 2025—one year after the Nevada court showdown—the Murdochs reached an accord that fulfilled Rupert's wish that Lachlan would inherit the empire. Under the terms of the deal, James, Liz, and Prue forfeited their voting rights to choose a successor, and each received $ 1.1 billion. A new trust was created that would benefit Lachlan and Rupert's youngest children, Grace and Chloe. The deal proved Rupert's philosophy that money always wins.

Everyone had reasons to settle. For James, Liz, and Prue, Gorman's ruling looked less certain once Rupert and Lachlan appealed in January. That uncertainty was made especially clear in May when Nevada appeals court judge Lynne Jones indicated she was sympathetic to Rupert's argument that he amended the trust to protect the business. "Who knows better than Rupert Murdoch the strengths and weaknesses of his family and his children?" she said in court. Donald Trump's election, too, had shifted the culture in Rupert and Lachlan's favor, according to one of their advisers. And Rupert's age also functioned as a ticking clock. At 94, he might not survive the appeals process. Despite all the emotional blood spilled, Liz and Prue wanted closure with their father before he died.

By the time it was over, the common front around the rebellious children had cracked. Liz resented being portrayed in the media as a plotter in James's coup-in-waiting. She never wanted to dethrone Lachlan—she simply objected to Rupert rewriting the rules. This was about principle, not power. But principle had limits. As her adviser explained of her decision to settle: "No one wants to be king of the graveyard. She could fight this, but by the time it ends, so much blood will have been spilled that everyone's dead."

Of all the siblings, James had positioned himself as the moral conscience of the family. He resigned from the News Corp board because of "disagreements over certain editorial content." He told The Atlantic that a good company wouldn't lie to "juice ratings." He funded progressive causes and spoke of reforming media. But when the moment came to fight for actual reform of Fox News—when he could have used his position to push for change from within—he took $1.1 billion and walked away. "Prudence, Elisabeth, and James are pleased that the matter is now behind them," James's spokesperson said. His moral awakening, it turned out, had a price tag.

For Lachlan, the battle left him victorious but vulnerable. To buy out his siblings, Lachlan sold Fox and News Corp shares that reduced his control over the companies' boards to 36 percent and 33 percent. That smaller stake means his perch is vulnerable to an activist investor in the future. Fox News remains as dominant as ever. In September, the cable network averaged 2.54 million viewers, more than CNN and MSNBC combined. But Fox's core 25-to 54-year-old demographic shrank 14 percent as news consumers increasingly got their news online from social media, TikTok, and podcasts. Tabloids, once the engine of the empire's growth, are now, on occasion, a liability. In January 2025, The Sun's parent company issued an "unequivocal apology" to Prince Harry for phone hacking and paid "substantial damages."

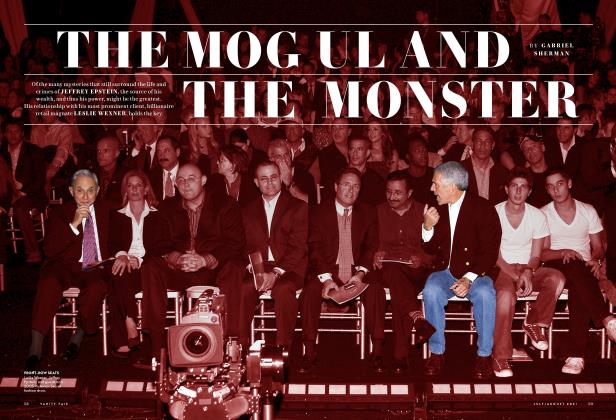

Lachlan is also navigating Rupert's fraught relationship with Trump. In July, Trump sued Rupert for $20 billion after The Wall Street Journal reported Trump had contributed a signed drawing of a naked woman as part of a 50th-birthday gift for Jeffrey Epstein, who was later convicted as a sex offender. "Happy Birthday—and may every day be another wonderful secret," Trump wrote to Epstein in 2003, according to the Journal. He denied making the drawing. Trump told people that Rupert deceived him. "Rupert assured Trump it wouldn't run," said a person who spoke with Trump at the time. The Journal stood by its story, with a representative telling reporters: "We have full confidence in the rigor and accuracy of our reporting and will vigorously defend against any lawsuit."

In September, despite his $20 billion lawsuit, Trump offered Rupert a minority stake in the consortium to acquire the US operations of TikTok. Rupert accepted— the man who once dictated terms was now taking what Trump offered. After decades building his empire through conquest and control, Rupert was now agreeing to be a minority stakeholder in a Chinese app. The Murdoch empire still mattered. Fox News still moved Republican politics; the newspapers still influenced elites. But power was shifting to platforms Rupert couldn't own and personalities he couldn't control.

Lachlan, Grace, and Chloe inherited an empire that, while still powerful, no longer set the terms of the game. Lachlan got the kingdom; James, Liz, and Prue got their freedom. In early August, a rumor swirled thro ugh New York media circles that Rup ert was very sick and possibly dying. But later that month, news outlets reported he had dinner with the Greek prime minister at a seaside taverna on the island of Tinos. During a month when billionaires gathered their families on their yachts, Rupert was with his fifth wife while his children were scattered across the globe. Hewas still in the game, even if he played alone.

Copyright © 2026 by Gabriel Sherman. From the forthcoming book Bonfire of the Murdochs: How the Epic Fight to Control the Last Great Media Dynasty Broke a Family—and the World by Gabriel Sherman, to be published by Simon & Schuster, LLC. Printed by permission.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now