Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPERFECT STRANGERS

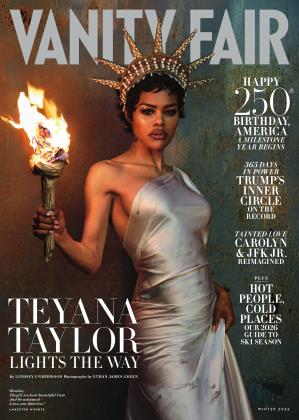

Her viral New York Times column "Was I Married to a Stranger?" devastated readers in 2023. Now, in her memoir, Strangers, BELLE BURDEN offers a deeper personal history, from a glimpse of her childhood at her grandmother Babe Paley's estate, Kiluna Farm, through the unraveling of a marriage that reshaped her understanding of family

BELLE BURDEN

I thought I had ended this legacy by marrying someone so steady so unassuming; someone who didn't have a public presence, someone who didn't flirt with other women, at least not in front of me. But I had repeated it in a spectacular fashion.

James landed on Martha's Vineyard just before 2 p.m. He drove down our driveway in a Jeep our caretaker had left for him at the airport, a model similar to the one he'd driven onto the ferry a month earlier. He walked up the brick path to our door. He wore a mask, so I couldn't see his whole face, but my first thought was that he seemed happy, his step brisk and optimistic. He was carrying an empty duffel bag over his shoulder.

He said he had only 90 minutes until he had to return to the airport. We gathered in the living room, on the side we rarely used, where two white couches flanked a large coffee table. I sat between the girls on one of the couches, my arms around both of their small shoulders. James paced back and forth in front of us, still masked, the glass doors of our living room and the expanse of the lake behind him. He said, "Mom and I are separated and we're going to divorce. I haven't been happy."

He continued to pace while he spoke, not looking at either of the girls, not looking at me. I watched him, thinking, The way he is moving and talking is so different. I don't recognize his body, his voice. Is he having a breakdown? Is he in love? Is he just delighted to be free of me, of us?

As soon as he said the word divorce, Carrie twisted her body to face the back of the couch. She was smiling; she thought hewasjoking. Then she looked at me, saw my grave expression, and shrieked. I tried to grab her, but she fled down the stairs, wailing in agony. Evie sat still and silent, with her arms crossed. James turned to me and said, "Em starving, can you make me a sandwich?" I stared back at him, shocked. I didn't know what to say in front of Evie. I tried to reason out an answer, Wouldn't a good mother make their child's father a sandwich? Wasn't this how the world said you were supposed to behave in a divorce? Be nice to each other in front of the kids? I said, "Okay, but please go find Carrie."

I went to the kitchen. With my hands shaking, I toasted slices of sourdough bread, spread mustard, layered turkey, sliced avocado and tomato, sprinkled sea salt. I thought, If I'm doing this, I'm going to do it well. I will not make a shitty sandwich. Maybe part of me thought that it would make him regret what he was doing. How could he leave a wife who made such good sandwiches? I thought this even though, in that moment, I didn't want him—this version of him—to stay.

I put the sandwich on a white plate with a bamboo rim and sliced it in half. I looked at our collection of cotton napkins and selected one in a blue flowered print. I roamed the house looking for him, carrying the plate and the napkin. He wasn't with either girl. Carrie was in the guest room, curled on the couch. Evie was in her bed, the covers pulled up, looking at her phone. Evie told me later that before she'd gone to her room, James had taken her out to the lawn with one of his slingshots, explaining that it was now her job to keep the geese away. He showed her how to insert the pellet, pull back the sling, aim, and shoot.

I finally found him in the basement. He had several cardboard boxes at his feet. He was squatting in front of them, rummaging through the contents—papers and folders and notebooks. I watched as he pulled down two more boxes. He was sweating with the effort. I asked him what he was doing. He turned to me with the same cold green eyes I'd seen the day he left.

He said, "I'm looking for our prenup. If you have it, you have to give it to me." The prenup was missing. My lawyer from 1999 had died, and his firm had no record of the document. James couldn't reach his lawyer, now retired. And neither of us had a signed copy in our email.

I stood there, at the top of the basement stairs, holding the plate, watching him. I told him to stop, to be with the girls during his remaining minutes in the house, but he continued, pulling box after box off the shelves. His duffel sat open on the floor beside the boxes, ready to receive what he found.

He finally gave up his search when it was time to go back to the airport. He ate the sandwich quickly as he stood by the front door. I told the girls to come say goodbye. They leaned against the banister, staring at him.

He said, "The ospreys are back."

I nodded. "Yes, we've seen them."

When he walked to the borrowed Jeep, the girls and I got in our Toyota, a big family car, to pick up Chinese takeout from one of the only restaurants open on the island. I wanted to leave first, before James. I didn't want my daughters to see their father drive away, his car disappearing over the hill. I feared the image would stay in their minds forever. I should have known it was the image of him pacing in his mask, not looking at them as he delivered the awful news, that would stick.

The girls and I ate together at the kitchen table, watching Gilmore Girls, as we did each night. We'd seen every episode multiple times, and the familiarity was soothing. My phone pinged. It was a text from James: "That was a great visit!" I stared at the sentence, stunned. He had rewritten the wrenching scenes we'd just lived, making them something different, something happy. I didn't write back.

A few weeks later, he sent an email with no message, only an attachment. It was a scan of the prenup. His lawyer had located it in a storage facility. When I opened the document and scrolled to the last page, I stopped at the sight of my own name. My signature looked innocent and hopeful, in blue ink and careful script, dated five days before our wedding.

In the evenings, after the sun set, once I cleaned up dinner and the girls disappeared to thenrooms, I had another expanse of time to fill. If I got inbed before 10 p.m., the night was unbearably long. I continued to rely on jigsaw puzzles, returning to the card table in the living room with a cup of tea, always in the same seat, methodically putting the pieces into place until the clock showed me some mercy, turning to the hour when I could end the day. As I sat working, I often felt the presence of several of my "deads," as my stepmother, Susan, called them—my grandmother, my father, and (childhood friend) Lynn, all sitting at the table with me. My grandmother, Babe, was to my left, my father across from me, and Lynn to my right. The feeling was strange; I have never believed in ghosts. But thenpresence was comforting. It felt like they were standing guard, protecting me.

I saw that my grandmother and mother had forgiven these men, that they d quietly cleaned up the mess, never saying a word about it.

Next to me, my grandmother's presence was warm, caretaking. Despite (or maybe because of) her failings as a mother, she had been a wonderful grandmother. She loved having me, my brother, and my older cousins at Kiluna Farm. She let us run wild, delighting in our presence, giving us her rapt attention. She insisted we join the adults at cocktails in the library, lunches in her garden, dinners in the dining room. To entertain us, she would arrange a large piece of lettuce or spinach in her teeth, smiling, pretending it wasn't there. We would dissolve into laughter, squealing, "Baba!," the name we called her, the name my children call my mother now. She cheered when my older cousin directed us in elaborate skits, performed for her guests after dinner.

She was tactile and affectionate. She always pulled me onto her lap, kissed the nape of my neck, and told me what flavor she tasted—honey, marmalade, lavender. We played patty-cake and backgammon. At bedtime she used her long red manicured nails to compose imaginary paintings on my face. She let me try on her jewelry, the two of us in front of her mirror, her graceful hands clasping necklaces around my neck, bracelets on my small wrists. She had fake versions of my favorite pieces made for me for Christmas, all perfectly arranged in a red lacquer box.

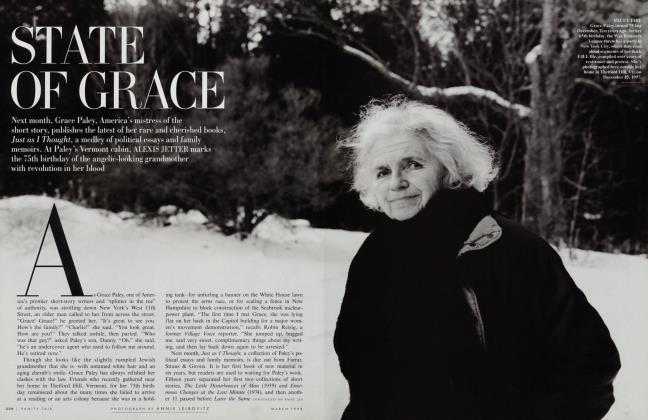

My grandmother was, and is, famous for her beauty and style. She was widely photographed, first as a model, then as a young woman in New York, then as a wife, first to my grandfather, Stanley Mortimer, then to Bill Paley. Images of her have become iconic—her face in profile by Richard Avedon; a Horst portrait of her wearing a colorblock dress, her wrists wrapped in pearls; a series by Slim Aarons at her house in Jamaica, casual in pants and a straw hat. She was meticulous in crafting her image, in how she presented herself to the world—her clothing, her hair and makeup, her jewelry, her homes, how she entertained. She cared about every detail. But her style was also natural, instinctual. It came easily. She set trends by the simplest action, like, famously, tying her scarf to the handle of her pocketbook. She was first named to the International Best Dressed List in 1941, and photographs of her are still printed, posted, and exchanged 80 years later, as new generations adopt her as a fashion icon.

But my grandmother was more than her famous image. She was brilliant, able to lead a conversation on any topic. She was funny. She read constantly. She was rarely at rest. She was an artist, drawing in pencil and sculpting in clay, skills she kept hidden from most of the world. Her father, Harvey Cushing, was a brain surgeon, and I think she inherited her intellect from him, along with her long, elegant hands. Her style was born from the same things—intelligence and artistry.

In a more modern era, she might have claimed her talents publicly, as an editor, a designer, an artist. But she was raised to be a wife, to support her husband, to be the perfect hostess, not to forge an identity apart from those tasks. Within these restrictions, she expressed herself in surfaces.

She died of lung cancer in 1978, the day after her 63rd birthday, when I was nine. I had not thought of her often in my adult life, usually only if I saw a photograph of her on Instagram, or when my brother and I reminisced about our time at Kiluna Farm. But she was very present in the days, weeks, and months after James left. I often woke up thinking about her, as though she'd been whispering in my ear as I slept.

There were, and are, persistent rumors that Bill Paley was a philanderer, rumors fictionalized and retold, in print and on television, like a game of telephone, the facts becoming murkier in each retelling. The rumors are now tied closely with the writer Truman Capote, who was, for a time, my grandmother's close friend and confidant. In 1975 he published a chapter of his unfinished novel in Esquire in which a man closely resembling Bill has an affair with a governor's wife. My grandmother was devastated by the publication of the story, presumably because Capote had betrayed her trust and her privacy, which she guarded fiercely, and co-opted her life for his own purposes. She never spoke to Capote again.

While my mother knew nothing of her stepfather's affairs, she grew to accept that he was unfaithful. It was a common phenomenon among rich and powerful men of the era, part of the package. My mother loved him anyway, as did I. We saw him often in the years after my grandmother's death, at his house at Lyford Cay in the Bahamas or in his apartment on Fifth Avenue. He often expressed deep grief over losing my grandmother and regret for not appreciating her enough.

My mother also had a pattern of loving unfaithful men, including both of her husbands and her beau of three decades, a journalist. She broke up with the journalist several times because of his infidelity, for the final time in 2018.

Without being conscious of it, as a child and a young adult, I absorbed this legacy of infidelity. I heard my grandfather described as "naughty," my mother's boyfriend as a "flirt," the betrayals chalked up to unavoidable temptation, a natural accessory to success. I saw that my grandmother and mother had forgiven these men, that they'd quietly cleaned up the mess, never saying a word about it. I felt, in my bones, an acceptance of men behaving badly, a value in not calling them out, in protecting a man's belief in his own importance, and a premium placed on keeping such things private.

I thought I had ended this legacy by marrying someone so steady, so unassuming, someone who didn't have a public presence, someone who didn't flirt with other women, at least not in front of me. But I had repeated it in a spectacular fashion. Unlike my grandfather and my mother's boyfriend, James seemed to have no regret, and he didn't want me back, The similarity was that he felt entitled to do it, and he expected me to stay quiet about it.

From the book Strangers: A Memoir of Marriage by Belle Burden. Copyright © 2026 by Belle Burden. Published by The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 118

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 95

In the living room each night, as I worked on my puzzle, with my grandmother's ghost sitting calmly beside me, I'd wonder, What is it about the women in my family that attracts this kind of betrayal? Will the same thing happen to my girls?

Did James have his own legacy of men behaving badly, walking out without explanation, of women stoically enduring it?

Did we both have another legacy—of adults remaining silent, never explaining what had happened, pushing it underground, into the subconscious lives of the next generations, creating a destiny where the bad thing could be, and would be, repeated?

Lynn, sitting to my right at the card table, looked as she did before she became sickbeautiful with dark curly hair, a spark in her blue eyes. She could be very blunt and told me once, early in my marriage, that she didn't understand James, she couldn't connect with him, which I took to mean that she didn't like him. Iwas defensive. But I asked myself now, Had she identified something I didn'twant to see—a coldness, an unknowability?

Now, in my distress, she wasn't gloating. She seemed to be reminding me of what we'd discussed many times: Everyone has something. This is yours. Each life has a defining crisis. This was, of course, an easy one, relative to many, relative to hers.

My father's presence, across from me, was intense. He was upset. It felt like he was saying, I trusted him too. I trusted him with you.

As James moved deeper into the investment world, I handed more of our financial life over to him. He understood the stock market, balance sheets, taxes. He could have the conversations with bankers and lawyers that I hated. Bankers and lawyers had always been tied up, in my mind, with the turmoil of my father's death. He told me how much money to wire into our checking account every month, the amount to pay in taxes. He dealt with the gas company, the landscaper, the accountants, the bookkeeper—anything and everything to do with money.

James was protective of me financially, always speaking up for my interests with my family. He also kept a sharp eye on our spending. Our transfers into our checking account, always equal, were small numbers; we were often in overdraft after I paid our regular bills, requiring another transfer. James preferred this scenario because he thought it made us more aware of our spending, what he called our "burn rate." He became agitated if our joint Visa bill was too high, a vacation too expensive. At hotels, he made me smuggle food to him from the breakfast buffet—hard-boiled eggs in paper coffee cups, a muffin in my pocket—so that we didn't have to pay one more cover. He asked me to annotate our joint credit card bills, explaining each charge in tiny print. Because of his anxiety, his watchfulness, I hid some things—the kids' clothes, their birthday and Christmas presents, my clothes—paying for them on my own credit card, the AmEx I paid myself, the one we didn't split, the one I didn't have to show him. My family paid other expenses for us, including school tuition and college savings plans for each child. It felt like another offering to James, taking these weighty costs off his shoulders.

He had excessive moments too, usually when it related to his passions. With his salary he could finally afford to buy the things he loved, and he didn't hold back: a dozen rare Ro lex watches, several motorcycles, rare coins, custom suits from Zegna, a small vintage boat that had been used inLive and Let Die, and expensive red wine, hundreds of bottles that we added to the ones I had inherited from my father, storing all of them in a climate-controlled facility in New Jersey. We acquired other things together—Berenice Abbott photographs of downtown Manhattan I gave James on his birthday, pets (a gecko, multiple fish, a goldendoodle), piles of our children's artwork, books, AmEx points—the stuff you accumulate when you are married, have kids, and have money. Our apartment, though still modern and minimalist, was filled with all of it. Layer upon layer of life, of comfort and security.

I paid our bills online and signed our tax returns, but slowly I lost touchwith both the big picture and the details of our financial life, depending on James to tell me what to do. I felt some shame about it, about not being involved, about not asking questions. But I was afraid I wouldn't understand it, that it was too complicated for me, even though I was a former corporate lawyer. I settled into the vagueness, the luxury and privilege of not knowing.

And part of me liked it, the handing over. James's care for our money felt like his contribution to our family, the way he showed his love and commitment to me and the kids. There was something romantic about it too—the smart and honorable man, the devoted husband and father, shouldering this part of our life. I had my own bucket of responsibility—the kids, their school, the meals, the homework, the bedtimes—so it made sense that he would take on our finances. We were dividing and conquering.

In the first weeks after James left, I parked my worry about what would happen to me financially in a corner of my mind. He said we would continue the "status quo," meaning our regular system of funding our accounts, paying bills. He had contributed his standard amount to our checking account on April 1.1 thought, At least I don't have to worry about this. He will not abandon me financially.

But the signed prenup glowed like a burning ember in my inbox. Before James's lawyer found it in document storage, I had started to believe it was lost. I thought, Maybe we never signed it? Or maybe we signed it but failed to deliver it back to our lawyers and lost it in the move to Broadway? Or, in my new mystical moments, Maybe my father had somehow, from beyond the grave, gotten rid of it?

The prenup would entitle James to an equal share of everything we had put in a joint name, including the house and the apartment. It would allow him to keep everything he earned during the marriage and kept in his own name, a number I did not yet know. This was the change we had made to the prenup in the days before we got married, the change James had requested.

When I found James searching the basement, I knew he wouldn't find the prenup. I had already opened every box, both the ones on the shelves and a bigger set in the crawl space—boxes marked with James's initials, sealed shut with packing tape. I used a box cutter to open each one and pulled out piles of papers, going through every page as I sat cross-legged on the cold concrete floor, the space lit by a single hanging light bulb. I placed the papers back in their folders, back in the boxes, carefully, neatly, and resealed them with tape so he wouldn't know I'd opened them. After six hours, I came out of the basement covered in dirt, dust, and sweat.

I didn't find it. If I had, I would have burnedit.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now