Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA GALSWORTHY TRAGEDY IN LONDON

Several Successful Comedies, and a Truly Parisian Triumph for Pavlova

F. S. THOMAS

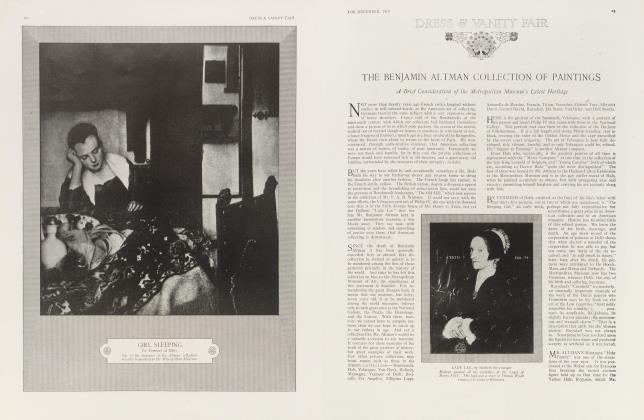

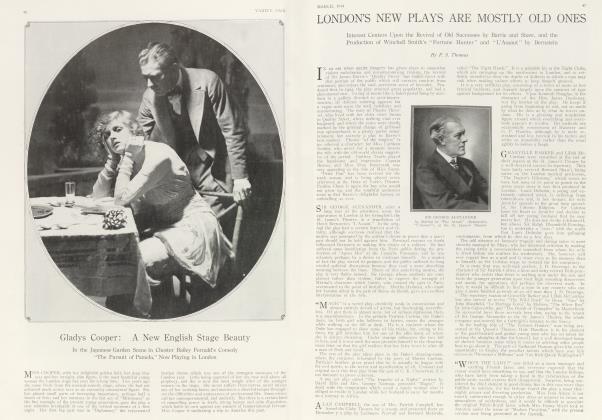

IN "THE FUGITIVE," John Galsworthy has written a remarkable play. It is a study of a type; a minute analysis of a woman, who rebelling against convention and monontony, bursts the bars of her cage only to be broken in a pitiful struggle against overwhelming odds. The play marches with relentless precision toward the inevitable — the woman's despair and death.

For those who go to the theatre to seek amusement, "The Fugitive" will afford but little satisfaction; but to the thinker, it will appeal as a well nigh perfect statement of a very real and absorbing problem. Clare Dedmond is the woman's name, and she is as complex as the average modern woman, — full of variable moods and vague ideals. "You are fine, but not fine enough," her friend said in summing up her character; and in that sentence lay the tragedy of her life. When the play opened Mrs. Dedmond had been married for five years to a wellmannered, exacting man, whose suburban soul soared to no flights beyond an occasional rubber o bridge. His wife was merely his chattel, and he regarded her in all matters of life much as a Turk regards the chosen lady of his harem. The two had drifted apart and had now reached the stage when daily quarrels were temporarily bridged by the affectionate reconciliations peculiar to a man of his type; and these reconciliations were the crowning horror of the situation to Clare. Into her life at this juncture comes Malise, a journalist encountered by accident during a trip abroad. He is an apostle of freedom, a teacher of fascinating truths and dangerous doctrines. Like a breath of air to a prisoner in a dungeon are these untramelled conversations to the unhappy wife; and blindly unquestioning she vibrates to the new and exciting influence.

MALISE is not a villain. He is merely absorbed in his theories and unable to understand how utterly these theories are unsuited to a woman who has always been sheltered and hemmed in by convention. He sees Clare being slowly crucified on the rack of matrimonial infelicity, and he suggests the only remedy which his training has taught him to suggest — emancipation.

That this woman, who is young and pretty, is absolutely unfitted to carve out a career, or even to keep her head above water does not enter into his calculations, for he is always more concerned with theories than facts.

IN THE first act, Clare fails to return home in time to receive her husband's father and mother whom he has invited to play bridge.

The situation ends in a violent quarrel, and it is easy to see that matters have come to a crisis. George Dedmond is angry, and not without cause. He points out that he has given his wife every comfort and that he expects obedience to his wishes. Clare retorts that she is stifling in the atmosphere of his home and his people, asserting that spiritually she and her husband are miles apart; but that

because she is his wife he is free to degrade her by a purely animal love.

WHEN the curtain rises on the second act, three nights have elapsed. We see the untidy sitting room of the journalist Malise. To him comes Clare Dedmond, to announce that she has taken his advice and left her husband. Malise is in love with Clare, but she does not yet return this affection. To her he stands somewhat in the light of a father confessor; so she leaves him and goes on her way to "earn her own living."

The third act takes place in the same room three months later. During these months George Dedmond has made ineffectual attempts to induce Clare to return to him, but with stubborn pride she has resisted all his advances. At last, driven by loneliness and lack of sympathy — she has been selling gloves in a shop — she comes again to Malise for advice and this time of herownfree will offers to share his life. So she hangs up her coat and hat.

WHEN George Dedmond discovers, through information obtained by detectives that his wife is now living with Malise he begins proceedings for a divorce. An old char-woman who has attended to the humble wants of Malise for some years presently reveals to Clare the fact that her lover is about to lose his post on the Watchfire, in consequence of the impending divorce suit. A journal of its distinction and standing is averse to the members of its staff appearing as co-respondents in divorce proceedings. The poor hunted woman feeling that she is a burden to her lover creeps forth again into the world, proudly and obstinately refusing to accept an allowance from her husband. "I will accept nothing for which I can give nothing in return." Then in six months comes the final event in this fateful chain of misfortune.

THE last act is so fine and so convincing that the memory of it will haunt the spectator long after the theatre lights are lowered and the audience dispersed. It is the poetry of melodrama. The setting is perfect — the corner of a supper room in the "Gascony," a smart restaurant frequented by the underworld. Delicately shaded pink lights, flowers, hot house fruits and obsequious waiters lend a realistic atmosphere to the scene. At the right, hidden by a screen, is a table which is presently occupied by a Languid Lord and his companion. But the table at the left of the stage is empty. Then slowly into the room walks Clare, dressed in a black evening gown into the belt of which she has thrust two white orchids.

The obsequious waiter, realizing that she is a stranger, beautiful, and therefore desirable, bids her sit at the empty table. She sinks into the chair vaguely. From another room comes the sound of a hunting horn — it is Derby night, and the racing world is scattering its gold. But she seems unconscious of her surroundings—and sits buried in thought. A dark, good looking young man passes the table, regards her with interest—asks her permission, then sits down. He finds her frozen attitude puzzling, yet irresistibly attractive. Champagne is ordered and while the waiter is opening the bottle he exclaims "Why, you are a lady! Are you stony?" She confesses that the cab fare and the bunch of orchids represent her last shilling. He offers to lend her money, but she shakes her head. She is as proud as ever, although the world has beaten her. She will take nothing for nothing. So she raises her glass and says with a pitiful smile "Everything has a beginning" —"le vin est tire, il faut le boire."

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 47)

THIS man is not a brute, but just an average man who takes his attitude from the woman. She has chosen her path. He is not there to preach. So he goes out to order a cab. While he is absent another male creature who has been hovering about casting furtive glances of admiration, comes up to Clare and asks her to have supper with him the following night. Vaguely she gazes at him. He takes her silence for acquiescence, and rejoins his friends. Loud laughter—a woman's—comes from beyond the screen. Something snaps in Clare's brain, she sees the horror of the future revealed. She cannot face it. Taking a little bottle from her gown she empties it into her glass and drinks the contents to the dregs. Then quietly, unostentatiously, she dies, her head drooping pathetically on her shoulder as the horn sounds merrily, and happy voices join in the hunting chorus, "For to-day a stag must die!"

IT IS the story of a woman who was "neither a saint nor a martyr; but who couldn't be a soulless doll." The last act is a wonderful piece of work, written in masterly style. Each effect is carefully studied and every word tells. It is life itself, cruel, relentless and unashamed.

Irene Rooke played the part of Clare with extraordinary charm and sincerity. The other characters were also well acted. It is more than likely that this absorbing play will soon be seen in America.

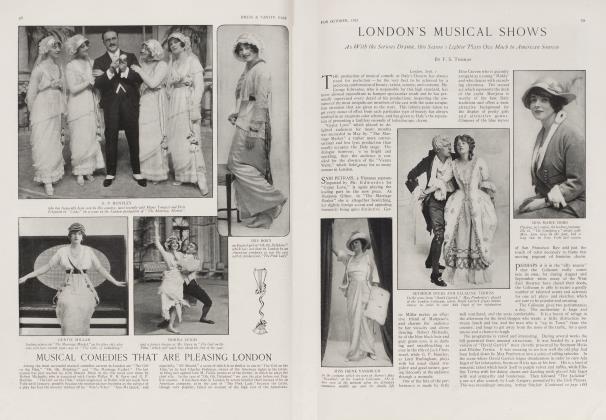

"INSTANTANEOUS success" is a greatly overworked phrase where the drama is concerned, but it seems the only adequate combination of words with which to describe the triumph Charles Hawtrey is enjoying in "Never Say Die." and his friends are congratulating him on having found so worthy a successor to "General John Regan."

The action of this American play in which William Collier created the leading role in New York last year, is changed to London; but Dionysius Woodbury remains an American as does Buster (who in New York was played by William Collier, Jr). The rest of the characters are English. The adaptation is cleverly made and Mr. Hawtrey wisely refrains from any attempt at an "American accent." The character of Dionysius Woodbury suits him to perfection, and although he appears somewhat robust and sweet tempered for a man suffering from "liver," and relegated to a spartan diet, he nevertheless manages to arouse everybody's interest and sympathy in the first act. In no city in the world, probably, do doctors take themselves more seriously than in London; and the dicomfiture of the two medical men in "Never Say Die" appeals immensely to the British public.

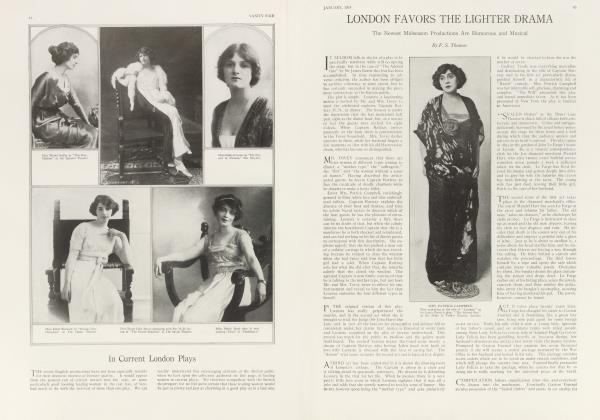

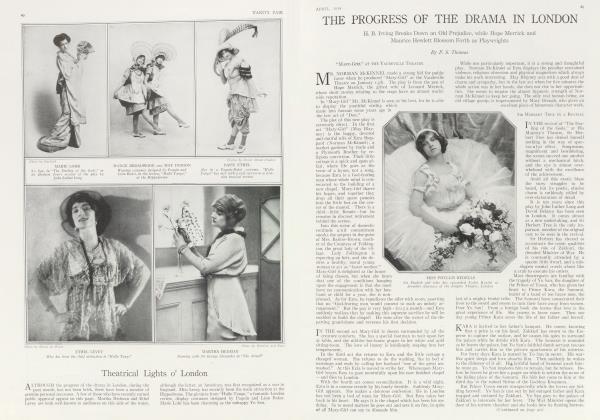

MARIE TEMPEST produced Henry Arthur Jones's play "Mary Goes First" at the Playhouse on Sept. 18th. It is a characteristic Jones play full of satirical sallies and hits at political jobbery. Marie Tempest in the title role has plenty to do; in fact, without her, the play would appear a very tame affair, for in these days of melodrama and highly colored farce, hair splitting discussion has become rather out of date.

The scene is laid in a provincial town in England, where Mrs. Wichello ("Mary") has held undisputed social sway. Her position is seriously threatened, however, by Lady Dodsworth whose husband has just bought himself a Knighthood. When the play opens "Felix Galpin" (Graham Browne) is giving a dinner to Sir Thomas and Lady Dodsworth as a sort of celebration of their new and important position in the town. The young man is placed in a most awkward position, for he is engaged to be married to Mrs. Wichello's young sister, and is therefore anxious to conciliate the exacting "Mary." The dinner ends disastrously, for Mrs. Wichello in a thoroughly "catty" spirit worsts the new Lady Dodsworth in every conversational encounter, and finally brings matters to a crisis by declaring that Lady Dodsworth's hair is dyed, and her face ridiculously made up, and that she looks like nothing so much as an "impropriety."

THE rest of the play revolves around this slanderous outburst, and the threat of Lady Dodsworth to bring an action of libel against Mrs. Wichello unless she apologizes in writing. The exact meaning of the word "impropriety" is liberally discussed.

"Mary" is not only a cat but a schemer and refusing to comply with Lady Dodsworth's demand, takes advantage of her gift for intrigue to straighten matters out. She persuades her husband to change his political views, and by pulling every wire at her command gets him elevated to a Baronetcy and a seat in Parliament. So she is again leader in Warkinstall.

In the last act, the chastened Lady Dodsworth in "her own hair" and natures's pallor was further humiliated at a second dinner by "Mary" who settles matters of precedence by taking the afflicted woman into dinner herself. It is a tempest in a teacup, where the water is kept in perpetual motion by the art of Henry Arthur Jones, and the vivacity and charm of Marie Tempest. Without these the play would be a dull recital of the doings of very mid-Victorian provincial types.

"LOVE and Laughter" is a real comic opera — not a hodge podge of six or seven people's ideas strung together by a clever manager. It has a charming and simple plot which is carried directly through three acts, assisted and not retarded by the songs and the dances. The scenery is artistic and the cast excellent. Oscar Strauss has written a most attractive score, and Arthur Wimperis has done good work with the lyrics. The plot is not novel, but it serves.

The Princess Yolande of Magoria is sought in marriage by Prince Carol of Phantaznia; but as the Prince is a rather careless and indifferent suitor, preferring war and sport to the gentler passion, he sends his cousin the Grand Duke Boris to inspect his prospective bride and bring back a report of her appearance. The Grand Duke Boris falls in love himself with the beautiful Princess and hatches a plot assisted by Hunyadi, the Lord Chamberlain, which will enable him to marry the Princess himself. In a tuneful song he informs Prince Carol that the Princess Yolande isa horror, lacking both in beauty and wit.

During the absence of Boris the Prince has met a fascinating gypsy maiden with whom he has fallen desperately in love at first sight. So he tells his cousin that rather than wed the ugly Princess Yolande he will abdicate. This exactly suits the schemer Boris. Of course the gypsy maiden is none other than the Princess Yolande in disguise, and things are eventually disentangled to everybody's satisfaction, and a war between Phantaznia and Magoria happily avoided.

THE wedding scene in the last act is a most gorgeous spectacle, the Court gowns of the guests being chosen in exquisite taste. Evelyn d'Alroy is charming as the Princess Yolande; and Yvonne Arnaud, as her lively gypsy maid with a taste for intrigue, has added laurels to her already heavy wreath. The funny man is an inventor of a small flying apparatus by the aid of which he carries love letters between Magoria and Phantaznia. There are terrible moments in his career, when sparking plugs and carburetors get hopelessly mixed, and the only thing that works is the horn, but he succeeds in capturing the affections of Zara, the gypsy maid, who finds his prowess nothing short of unique.

Sir James Barrie has mastered the art of "tragedy in a capsule" in "Half an Hour," the three-act play which is now being produced at the Hippodrome following its initial presentation in New York at the Lyceum Theatre. There is no art more popular at the present moment apparently than the art of compression. Miss Irene Vanbrugh scores another success as Lady Lilian Garson, the part created in New York by Miss Grace George.

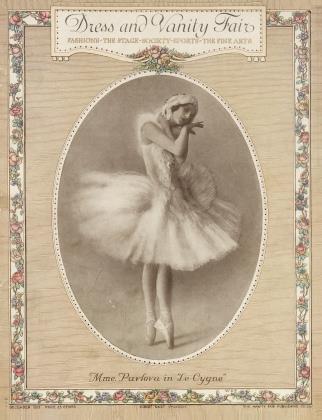

MME PAVLOVA'S two farewell matinees at the London Opera House were both occasions of veritable ovations. The enormous house was packed from stall to gallery, and the fascinating Russian dancer was literally bombarded with flowers of every description.

It would be difficult to say in which part of the programme she won the greatest applause, because the whole performance was greeted with an enthusiasm more characteristic of Paris than of London. Women tore the flowers from their belts and cast them at her feet: and in their midst Pavlova stood, smiling the mysterious dryad smile for which she is famous.

GISELLE" a Russian tragedy, opened the last afternoon's performance. This beautiful dance-opera has been given by the Russian Ballet, but with quite a different setting. Pavlova casts aside all mechanical devices in her interpretation of it, and achieves her effects rather by the supreme perfection of her art than by spectacular contrivance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now