Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOf Canned Music and Customs

The Harp of Yesterday Has Become the Phonograph of To-day

STEPHEN HAWEIS

THERE is an old story of a mediaeval inventor in Italy who discovered a method of making an unbreakable glass. Filled with the enthusiasm of all inventors, he looked forward to a time of regeneration when those who lived in glass houses need not fear thrown stones, and topers might sweep the glasses off the bar without extra charge. According to the custom of the time, he made a beautiful beaker of his new ware and sought the local leader of Rank and Fashion. After drinking his health and wishing him a long list of inexpensive wishes, he raised the cup above his head and dashed it upon the ground where, to the astonishment of all who were privileged to be present, it did not break or chip, but when it was picked up proved to be only a little bent.

The inventor expected a wad of money for that stunt.

The local leader of R. and F. was more than astonished,—he was genuinely terrified. And he ordered that the magician be taken out into the back yard and tapped smartly on the back of the neck with a crowbar,—twice, if necessary.

IT may be that this was not altogether a just and wise proceeding, but there are moments when the plan seems to me to have something to recommend it, and I regret that our modern wizards,—or some of them,—have such an easy time. I live in unwholesome intimacy with something more than six phonographs. Just how many are working now I do not know, for my ear is only trained to the combinations of four,—after that it becomes abstract, and not particular, noise.

Life is full of compensations, however. Sometimes they are all silent together and then there is nothing to disturb the exquisite peace but the typewriter immediately next door, which allows nothing to hinder it, night or day.

I used to think that I was musical, but I know now that I prefer the typewriter to the violin, and anything in the world to those unspeakable songs about Ireland. Song indeed should be under direct State control; singers should be licensed, and licenses granted only under the most exacting circumstances and the severest tests of necessity.

TS7HAT is the reason of the immense ™ popularity of the phonograph? It has touched the heart of man very deeply. It is a symbol, a terrible tinkling symbol, and a mirror in which ninetenths of the populace finds itself reflected. It is the coffin of good music end the means whereby the bad attains to a spurious immortality. It is but a little wooden casket, containing simple machinery designed to turn a disc. It has none of the sweet limitations of its delightful prototype, the musical box, which tinkled "The Last Rose of Summer" to our enraptured grandmothers. It will play whatever record you place upon its green baize lap, contributing of itself only a faint buzz,—not always faint, at that, and usually sufficiently audible to spoil the music, except the music be of the basest and most raucous type, when the lesser horror is swallowed up in the greater. There *is a slight difference attainable by using different needles; they are like our changing moods, expected, unvariable, infinitesimally different from one another. What record is offered to it is largely a matter of accident, and anybody can turn the handle. Alas, almost anybody can turn the handle: does not that describe most people?

As a social factor, the phonograph slowly effects a gradual attenuation of the intelligence, and possibly, at last, the complete destruction of the soul. In the guise of education and "uplift" it is certainly a destroying agent. For years we have deplored the decay of the art of conversation. If you hear a brilliant remark at a dinner party in these days you know just where it comes from— that is, if you read Vanity Fair. Can anyone be brilliant near a phonograph? Can anyone talk through it? You no longer fear to offend the musician, but you offend the owner,—he who prefers to turn the handle of his infernal machine rather than exert the remnant of his shrivelling brain to entertain you, after he has not only invited you to come, but made it impossible for you to refuse. To such a pitch has it got that he does not even wish to be engaged in conversation. He is so afraid that you may talk of something he does not know about. Under pretext of his love for music (implying a sensitive soul among provincial lowbrows) he stops all possible conversation which might disclose his abysmal lowbrowity by asking if you know that thing from "Carmen," and then he winds the handle and wanders aimlessly about the room murmuring, "Torry a door, Torry a door!"

What he loves in the phonograph is what he loves in literature. It plays music on the same terms that bestsellers express emotions and do his thinking for him. He feels that something is going on. It obviates the need for any personal mental process whatever, and administers the lead pipe to the intelligence in a way that nothing else can. At last "the tired business man" welcomes what he conceives to be art. "Do I not love art? Yes, sir, for that machine I paid two hundred bucks,—without any records."

TT may be that all is due to the hurry in which we are compelled to live, but the modern craze for speed is not without reason. Speed gives the maximum sensation with the minimum of trouble and is itself nearly as effective in arresting human intercourse as is the canned music of our homes.

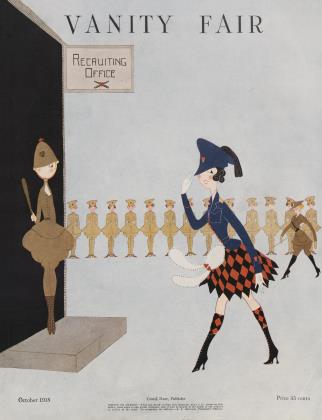

'T'HOSE who remember the delicious manners of sixty years ago know how great is the difference between the lovemaking then and now. In the quaint custom of those remote days, the man would seem to have taken quite an interest it it; there was so little to amuse us then. The procedures are rapidly becoming a matter of folk lore, known only to students. He carried the flowers and candy himself in those days, and racked his brains for jeux d'esprit with which to delight his lady. He sent her original verses resembling the Valentines of a still earlier period.

Who, to-day, would believe the customs in vogue when gentlemen nonchalantly combed their full-bottomed wigs, in the drawing-room? The harmless harp, designed as a setting for a lady's beauty, was the phonograph of that day. And lovers gave to their mistresses nosegays in which were concealed tricorne notes and perhaps a patch box with such mottoes as:

"If you my love accept of this Reward the giver with a kiss."

But now, He gives an order for flowers and candy to be sent till further notice. If he inherits anything of the sentimentality of his ancestors, he may include the phonograph record of "The Sunshine of Your Smile" among his purchases.

Imagine the effect of a hundred years' sunshine of your smile and the like, operating in the same ratio on youth and love!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now