Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMemories of the Man and the Artist

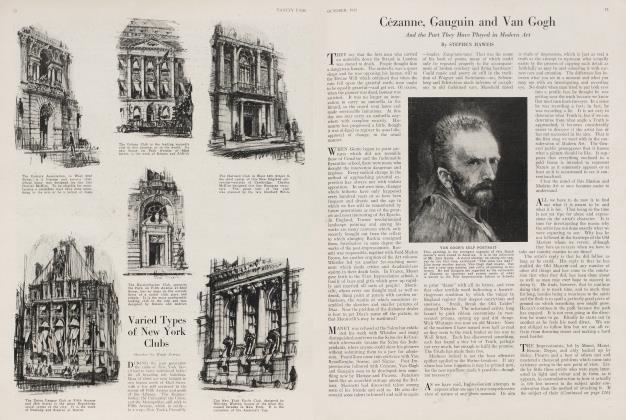

June 1918 Stephen HaweisIF I ever live long enough (which Allah avert!) for my reminiscences to be a subject of general curiosity, the thing that will count most in their favor is that I knew Auguste Rodin.

Many men may write of Rodin's Art; explaining, labelling, disputing, comparing; but he has said the last word about himself in deathless stone and bronze, the word that is polite to adulation, indulgent to abuse. He proclaims himself the culminator of one era of sculpture, the inspirer, and nearly the author of another. He was the father of the various schools which are lumped together under the title of Modern Art.

Few men ever did as much work as Rodin in any walk of life—judged by actual quantity. As a craftsman, few can pretend to rival him in the quality of his work. Since the Greeks no one has ever finished a marble as he could finish it, and his bronzes seem to be moulded with his own hands, so much are they of himself.

Sculptors will tell you that he was no sculptor, meaning that he lacked, to some extent, the monumental sense that the Egyptians possessed in so marvellous a degree. Sculptors will say, scornfully: "Compare him with Michelangelo!" tacitly admitting perhaps that to none other save the greatest since Phidias can he be compared.

But lovers of Rodin's art can compare him with Michelangelo without detriment to either master, for they say: "Michelangelo invented and created a race of Gods, a Dante in stone, while Rodin moved among men with the music and fluency of a Swinburne but with the thought of a Whitman. Their problems were not the same. Rodin never sought "behind the heavens" for a "motive. He . was a Nature worshipper; he loved the beauty of "La Pensee" and the ugliness of "The Man With a Broken Nose" with an equal love. He knew that the body and the soul were one; he knew that they were one with all that has life, and if that One were not God, he knew no other.

"Je ne suis pas un marchand," he once said to me, "je ne vends jamais rien!" Here in my studio is all my work, it is one thing. Nothing ever left his hands but that he had a copy, and this great life's work in its entirety is now the property of the French nation.

IT was in the days when Edouard Steichen showed the world what could be done with the gum-bichromate process in photography that I began to tinker with a cheap camera in an amateurish sort of way. I wasted much good material, but some of my best results were shown to Rodin, who, the friend of all photographers, at once invited me to work for him. I soon found that what he required was not technical photography—he could get all he wanted of that—what he required and loved were the wild experiments I delighted to make. Very often my worst failures met with his warmest praise. "C'est encore mieux que Steichen," he once said delightedly of a mixed bunch of prints, and "mieux que Steichen" became the slogan for any particularly unlooked for result.

Photographic interpretations of his work, good, bad and indifferent, stimulated his imagination and he never tired of them.

For his own portrait he could stand like a rock, any time, anywhere, in any garb. He would supply the conditions and one had to make the best of them. The exposure was never too long for him. The best portrait I made of him was from a peculiarly bad negative taken in his dressing gown against the rising sun, as he stood in the field behind the Villa des Brillants at Meudon. He wore, I remember, a huge pair of sabots to protect him from the dew.

RODIN'S home at Meudon was a strange household. The vast studio, moved entire from the Avenue d'Antin after the Exposition of 1900, was his real home. Beside it there stood apologetically, a small house which was never furnished. Dozens of pictures given him by distinguished artist friends all over the world stood round the walls, on the floor with their faces to the wall, among which were many indifferent works purchased by himself—often from the despised Salon des Indépendants.

One, I recollect, moved me to mirth by its frank incompetence, but Rodin saw something worthy in it. "There is force," he said, "there is a striving—il y a quelque chose." And he had bought it for the striving in it.

Every room in the house was alike—open, bare, austere. A few pieces of fine furniture, some Greek vases and Etruscan fragments, a half assembled four poster bed without a mattress, beneath which drawings by Puvis de Chavannes and lithographs by Whistler rubbed corners with Meryon's etchings and Conder's painted silks.

Only in his bedroom was there a mite less confusion. Two paintings by his lifelong friends, Carriere and Monet, hung on the wall; a simple bed, beside which, upon a little table, stood a volume of Richer's "Human Anatomy," and a candle, light reading,—if he happened to waken in the night! I believe it was almost the only book he ever read.

FEW ever came into contact with Madame Rosa, his wife. In her youth she was the original of the "Bellona" and many another lovely head. She presided over the kitchen, where she prepared the bowl of bread and milk he took for his petit déjeuner as regularly as the sun rose. It is said that many a great lady coveted the title of Madame Rodin, but, three weeks before her death, Rodin married Rosa, the devoted companion of his life, one instance at least of a "union libre" which was no failure.

Once, over the dinner table in the garden, when we.were discussing the poverty of art students Rodin remarked that when artists had no money they had to live on their wives—"Hein? n'est-ce pas, Rosa? We've all done it. In the old days she used to do sewing-." "Tais toi, done, Auguste!" said the old lady hurriedly, pink with embarrassment and—perhaps—joy, as she hurried away from the table to fetch the potatoes, done, as she explained, just in the way the maître liked them best.

He had then lately returned from England where he had been feted by Duchesses and where the Academy students had taken the horse from his carriage and dragged the carriage themselves. "Ah, e'etait la folle fête!" And he had tasted the Lord Mayor of London's famous turtle soup. He didn't know what it was made of, exactly, but when I told him he suggested that Madame Rosa should buy some tortoises which he had seen on sale in the streets of Paris. I think he was a little sorry to hear they wouldn't quite do.

ONE day Rodin showed me the entire set of drawings that he made for Octave Mirbeau's "Jardin des Supplices," and, pleased I think by my ignorant enthusiasm for certain of them, took me up into the attic to search for some of the originals that he meant to give me. He couldn't find them; alas, but I came upon a heap of old canvases there of which he feebly professed to be ashamed, though I think he loved them dearly.

He tried his hand at painting landscapes a little, in Belgium, in the long ago days when he worked as "ghost" for Constantin Meunier. I believe I am one of the very few people who ever heard him talk of these attempts. I wonder where they are now; they would not establish him as a master of oil paint exactly, but every work from his hand is of interest and value.

There were always half a dozen sculptors working upon his marbles, under his eyes, and it was amazing how completely he always knew what they were doing, even on Saturdays when he permitted the distraction of an almost continual flow of visitors.

He loved flattery, as all human beings do, and would listen attentively to rhapsodies from almost anybody, though they do say a pretty lady got more attention from him than a half starved journalist. Often, visitors would supply a name for a statue or group which appealed to him and then he would reach out for a pencil and write it on the plaster at once. He didn't think much about his titles. The title came last and was often very impermanent, as for example the "Ugolino," which he often called "Nebuchadnezzar." Externals, however, never took his mind from his work for an instant; without a shadow of warning Rodin would dash through his admirers to rebuke, warn or advise one of his "ghosts." His eyes were everywhere. Nothing ever disturbed him save errors in his work.

The mass of the studies which he left behind him .was appalling. To me, those innumerable studies—tiny hands, tiny faces, tiny feet—are even more wonderful than his larger statues. He never tired of recommending them as a method of study to young sculptors. "When you can model a hand as large as the top of your thumb you can model anything," he would say, and he himself must have made thousands upon thousands of them in every conceivable position.

The best no doubt were handed over to the "moulders," of whom he kept four or five continually employed in making plaster casts, but those that still remain are only a small percentage of the quantities which one squeeze of his noble thumb obliterated.

NOT many "bon mots" are recorded of him. He had not the conversational brilliance of Degas or Whistler, but one may be recalled here. It was his custom to go round the Salon each year with Degas and Besnard, and, while they were all silently appreciative before each other's works they became very candid and critical before the rest of the exhibits. It was the year that Vibert—a master chemist of painting but a very poor painter—had published his great work upon Colors and Varnishes. In it he had explained the enduring qualities of pigments. Rodin had heard much of the permanence of pigment. The Trio stood speechless before Vibert's salon picture of a group of cardinals quaffing beakers of wine. Degas and Besnard were dumb, their attitude one long silent exclamationmark of contempt, but Rodin sidled up to the little picture, with its brilliant reds and faultless surfaces, and regarded it closely. Then he heaved a deep sigh: "Penser," he murmured sadly, "penser que ça ne changera jamais!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now