Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

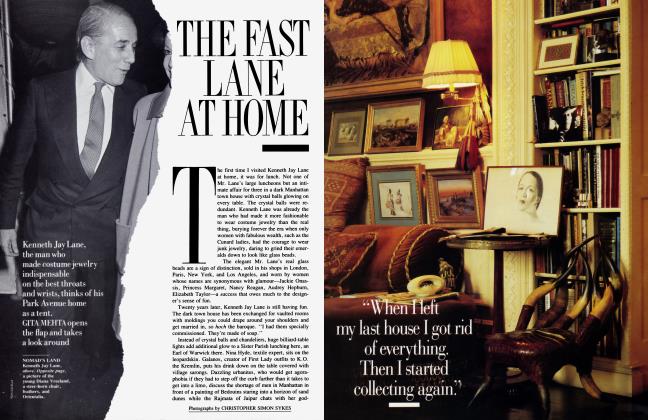

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRothschilds, royals, and the cream of literary London are expected next month for the centennial of Everyman's Library, and to celebrate David Campbell, whose beautifully bound, affordable classics turned the moribund imprint into a financial success. With the same bravura style, he has restored a 1790 Palladian ruin in the Scottish Highlands. DAVID JENKINS meets the dashing master of Barbreck

February 2006 David Jenkins Christopher Simon SykesRothschilds, royals, and the cream of literary London are expected next month for the centennial of Everyman's Library, and to celebrate David Campbell, whose beautifully bound, affordable classics turned the moribund imprint into a financial success. With the same bravura style, he has restored a 1790 Palladian ruin in the Scottish Highlands. DAVID JENKINS meets the dashing master of Barbreck

February 2006 David Jenkins Christopher Simon SykesPublisher David Campbell has a flair for restoring old institutions that's in defiance of all common sense. Only Campbell could have seen the potential in Everyman's Library and recruited such supporters as Mick Jagger and the Prince of Wales when he bought the ailing imprint in 1990. And only Campbell would locate the worthy Everyman above a sex shop in London's raffish Soho district.

At the 1991 relaunch party in Spencer House—Princess Diana's ancestral home in London—Jagger let it be known that he had bought three complete sets of Everyman's exquisitely bound collection. (Then consisting of 50 books, it included Pride and Prejudice, To the Lighthouse, and The Wealth of Nations.) As for Prince Charles, he has, as Campbell says in his emphatic, upperclass tones, "always been a keen supporter," and he is expected to be there on February 15 when Campbell, 57, throws another party, this time for about 350 people in the Fine Rooms of the Royal Academy in London, to celebrate his imprint's centennial. Mick, alas, can't come—it's "a drag," he has e-mailed, but he's tied up with the Stones that day. Still, there should be a slew of Rothschilds and probably a platoon of Amises and Rushdies.

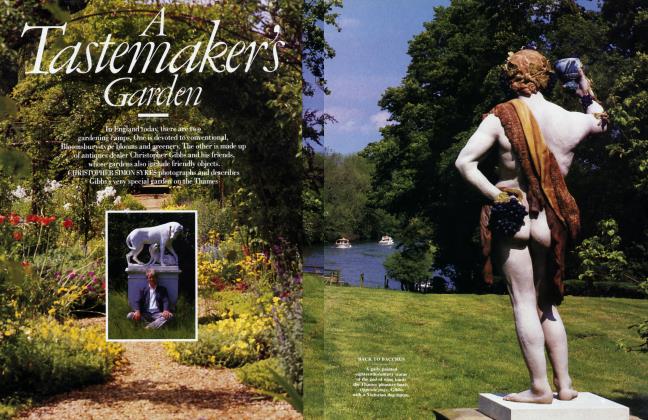

It's Campbell's bravura which makes him "attractive to women and yet a man's man," as one observer puts it, and which has enabled this once moribund publishing house to print more than 12 million copies of nearly 500 titles in the last 15 years. And it is the same daring vision that in 1985 inspired him to buy Barbreck, his ravishing Palladian house in the Scottish Highlands, when it was all but a crumbling ruin.

At the time, he owned another Georgian house, in London, that had just lost its roof, and he recalls there were those who felt "two roofless Georgian houses was one too many." The first summer Campbell spent there with his wife, Alexandra, his son, Charles, and his daughter, Iona, it rained and rained. They "ate like Pathan tribesmen crouching round a fire outside," he remembers. But Campbell saw that the house was as strong as "the Pyramid of Cheops"; it just needed "tweaking and a little T.L.C."

It got it. The house, which dates to 1790 and was built by a member of the Campbell clan in the traditional family territory of Argyll, has been as beautifully restored as Everyman. Most activity takes place on the first floor (what Americans would call the second), which is reached by a cantilevered stone staircase. That first floor, with its 14-foot-high Adam ceilings, includes a study, a dining room, and a drawing room. Above are six bedrooms, while the ground floor is largely given over to a hall full of Wellington boots, fishing rods, and the swords, lances, and shields that would have been used by Campbell's bellicose ancestors. Some of the furniture belonged to Campbell's grandfather: "There was no money but a lot of quite good and quite big furniture and paintings. So I was either going to have to find a place for them or sell them and buy small furniture for a small house."

In the distance is the island of Jura. Campbell enjoys taking guests there for picnics, driving his boat past "the most dangerous whirlpool in Europe. Completely calm most of the time, but occasionally can be very, very dangerous. And I have been known to run out of petrol."

In the house, there is music, "a certain amount of wine," and excellent food. Campbell grows his own oysters, so there are three to four thousand at hand. It's fun, he says, to pop down before lunch and pick "a few dozen."

Campbell saw that the house was as strong as "the Pyramid of Cheops ; it just needed "tweaking and a little T.L.C."

It's a very agreeable life, and one brought about by Campbell's two defining traits: optimism and acumen. Back in London, those characteristics allowed him not only to see that Everyman was "28-karat" but also to sell the product. "If you're very obscure or small, as we were, you've got to punch above your weight. Your books have got to look more beautiful and be more acutely priced." Paperbacks had become "foul" and expensive. So his books have sewn cloth bindings, and acid-free paper that doesn't discolor with age. Many cost only a few dollars more than a paperback. And they're timeless: one of this year's strongest sellers, Campbell says, is Dante's Divine Comedy. "It's got the Botticelli silverpoint drawings no other edition has."

Campbell brings a dash of romance to a mercantile age. He's like the hero of a thriller: an old Etonian, educated at Oxford, who's always had an eye for adventure. No wonder "the Oxford Appointments Board kept trying to make me a spy." It wasn't to be: post-Oxford, Campbell drove with the Maharajah of Jodhpur and another friend across Central Asia. Of Campbell, Jodhpur says, "David's enthusiasm and hyperbole know no bounds."

He has buckets of élan too. Campbell rides to work at his London office on an old-fashioned bicycle with a basket over the front wheel: "I'm probably the only head of a publishing company who occasionally delivers a book by hand." He can also display a regal disdain for the diurnal life of the deskbound. According to his longtime friend Sonny Mehta, chairman and editor in chief of Knopf (which publishes Everyman in the U.S.), "Everybody is charmed by David's exotic absences. You try to call him and he's off fishing in the Falklands."

Right now, though, Campbell is worrying about his party. It is indeed a "drag" about Jagger; a literary-minded pop star has more media pull than a prince. But there is in London one pop star with a children's book to her name. And ... well, here's Campbell speaking the words written on a postcard he once received:

"Surprise No. 1: Madonna has a library.

"Surprise No. 2: it's full of Everyman."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now