Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Spread of Bad Art

Alarming Statistics to Prove That There is More of it in the World Year by Year

ALDOUS HUXLEY

I KNEW a young man once who committed suicide, not for any of the ordinary, classical reasons—love, debt, impending disgrace or mortal disease—but simply because he found the world too intolerably second-rate to be put up with any longer. I regretted his death; for though he was never exactly a friend of mine—indeed, I doubt whether he was ever anyone's friend—I found him a delightful companion. He was intelligent, he was erudite, he was variously talented, he had faultless taste—such good taste, indeed, that there was practically nothing that did not strike him as vulgar; just enough talent to enable him to do many things charmingly, as an amateur, and none really well; learning in sufficient quantity to make him realize his own and all other men's bottomless ignorance, and so much intelligence, coupled with so little enthusiasm that nothing whatever seemed to him worth doing. There was nothing left but to commit suicide. He was logical; and he had the courage of his convictions.

WHAT distressed him most was the fearful mediocrity of contemporary art. He complained that there were more bad artists in modern times than there had ever been in the past. Bad art, in the shape of silly novels, drivelling plays, sentimental music and vulgar, or dully pretentious pictures, haunted him like a guilty conscience. Another man would simply have been at pains to avoid these manifestations of bad art. But just as, when one suffers physically, one cannot resist fingering the half-cicatrized wound, or touching the aching tooth which is the source of the pain, so he, who suffered so acutely from bad art, could not ignore it, but was perpetually lacerating his spirit by the contemplation of what he so much detested. He read all the popular favourites, never missed a first night, spent whole days in the Royal Academy and all the various Salons, from the official to that of the independents, assisted at every performance of a work by Saint-Saens or Rachmaninoff. What he suffered—he who was distressed by the stupidity of Swift, the vulgarity of Shakespeare, the platitude of Goya and the coarseness of Mozart —what he suffered, reading those books, seeing those plays and pictures, listening to that music, cannot be imagined. Only one thing is certain; he killed himself.

I used to listen to his jeremiads with amusement—for he could denounce wittily. But I never took what he said very seriously; for at that time I had not yet taken to literary journalism. I had no knowledge of what bad contemporary art really was. Since then I have reviewed several thousand books, attended professionally some hundreds of first nights, private views and concerts. What my poor friend did out of a morbid love of self-laceration, I have since done in order to earn money. Le borborygme d'un estomac qui soujfre was my excuse; but he was an amateur of independent means. I swam in the muddy tide of bad art in order that I might live; he, in order that he might die. But, for whatever reason, I too swam where he had swum. If he were alive to-day I should listen to his complaints and denunciations with a great deal more sympathy and understanding than I listened in my days of innocence. And I should have, moreover, certain reflections to offer him—reflections which, while they might not have consoled him for the badness of contemporary art, might at least have explained why that badness took precisely the form it did; and by turning his mind from the contemplation of the thing itself to the contemplation of its causes, might have changed his passion for self-laceration into a passion for scientific enquiry.

But these reflections were not made, alas, till after he was dead—for the good reason that it was not till after his death that review copies and free tickets had forced the problem of bad art on my attention. So far as he is concerned, these reflections are a piece of esprit d'escalier that has come to me some five or six years too late. Still, such as it is, the esprit has come. And it seems a pity to waste it, the more so as the subject is not uninteresting. "Why is bad art—or at any rate, why does bad art seem to be—more copious now and of worse quality than it was in the past?" Without being a matter of life and death, as it was to my poor friend, that question is one that must have presented itself in one form or another to all who occupy themselves at all consciously with the arts.

Let us begin with the obvious. There is more bad art in 1925 than there was in 1625 for the simple reason that there are many more people in the world than there were then, that these people can almost all read and write and that they dispose of a, comparatively speaking, ample leisure. That leisure has got to be made tolerable. The traditional arts of selfamusement have been mostly lost; education and a snobbish desire to imitate the rich and cultured have killed the morris,, the maypole, the folk song, the mummers. Nor is it possible, as a matter of fact, to practise most of these entertainments in the crowded cities in which the great mass of human beings now live.

THE supplying of diversions ready made has become a profitable industry. To own a merry-go-round is profitable; to have written a successful novel is still more profitable. Playwrights can earn more than company promoters, composers can afford large motor cars, a skilful draughtsman can make enough to support three wives in luxury. Not all of them do, of course; but all have a chance. Millions and millions of human beings, terrified of boredom and enjoying a leisure which they are powerless to fill themselves, are hungrily craving for distraction, are begging to be relieved from their own intolerable company and to be given substitutes for thought. The man who can give what the greatest number of his fellow beings require is made for life. All the worst works of art are created to supply the hunger of the greatest number. -Incidentally, a few of the best do the same.

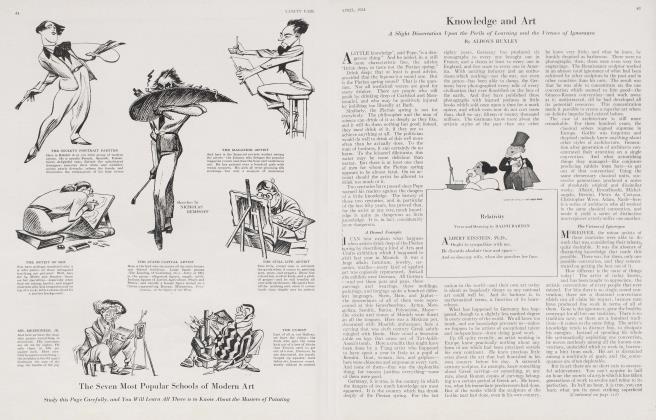

Education and leisure have enlarged the public which patronizes the arts; and the greater public's increased demand for art has correspondingly enlarged the circle of those who, by purveying what it requires, live professionally on its patronage. But education has had a further effect; it has caused an enormous number of people who, in the past, would either have done nothing at all, or done some useful work, to profess themselves 'artists' and produce 'works of art'. The decay of formal religion has had many deplorable effects, of' which perhaps the worst is the exaltation of the idea of patriotism and the most harmlessly absurd cult of High Art. Earnest young people who would in the past have been regular church goers, now devote themselves to Art and imagine that they themselves are artists.

Many, it is true, abandon their artistic aspirations once they are fairly grown up and launched into the world; but many, very many, (particularly of those who have a small independent income) go on imagining themselves to be artists to the day of their death. To them is due that vast mass of dull, respectable, flabby art which goes trickling, like a semi-liquid mass of unleavened dough, over the face of our modern world. All the flat novels, all the baring, competent poems, all the blank verse tragedies, all the insipid performances of Bach, all the dim water colours and the dreary still lives are their work. It is they who, with heavy footed enthusiasm, follow in the track of the pioneers, strewing the world with lifeless imitations of living art.

IT is better that they should do these things than that they should spend their lives between the race course and the night club (though I am not perfectly sure even of this). But it would be much better still if they blew off steam as their ancestors did, by going to church, praying and doing good works.

The artists who are artists because it pays them to be, and the artists who are artists because they no longer believe in an organized religion and must have something to satisfy their higher feelings—these arc responsible for all that is peculiarly vulgar and peculiarly dull in contemporary art. Neither class was anything like so numerous in the past.

It might be remarked in passing that the spread of education has had yet another result, which is a great raising of the level of technical accomplishment in most classes of art. The average popular novel is far better written and put together than it was in the past. All that can be taught about art has now been learnt by its practitioners. But bad work is no better for being technically well done. Indeed,

I am inclined to think it is rather worse. There is a certain charm about ingenuous and untutored badness. But when bad artists arc like the average French novelist of the present day —accomplished, knowing all the tricks of the trade, working according to the best recipes in the literary cookery books—then they are utterly insupportable. The untutored bad sometimes achieve a kind of excellence by mistake. The tutored never make mistakes; they are consistently and efficiently bad all the time.

Continued on page 86

Continued from page 37

It would be easy to enumerate other factors in modern life which have made contemporary bad art; bad in a peculiar, unique, twentieth century way. Thus, our habit-of hurrying has killed the long book, our bourgeois way of life has killed the large and grandiose picture, our widely diffused knowledge has led to eclecticism and catholicity of taste, w'ith consequent pastiching of every kind of ancient or far-fetched style. Particularly striking is the influence of the camera on the visual arts. Daguerre's invention has reacted on painting in a number of curious and unexpected wrays.

In the first place, photography has tended to make the modern painter much less interested in the exact imitation of nature than he was in the past. The camera can do the job so much more quickly and easily that it seems hardly worth his while to strain after exact likeness. Cubism, expressionism, post-impressionism and all the other brands of non-realistic art, together with the whole modern theory of aesthetics have been made possible by the camera.

The making of exact (and beautiful) imitations of nature was one of the principle functions of the secondrate artists of other days. The camera has now robbed these worthy second-rate artists of their occupation. Modern theory tells them that they ought to produce something purely aesthetic and formally significant. They do their best—and the result is that unspeakably dismal second-rate 'advanced' art wrhich fills the galleries of the contemporary w'orld.

In pre-photographic, pre-'process' days, the work of engraving occupied the energies of a very large number of. conscientious, technically competent and entirely unoriginal artists of the second rank. The public wanted reproductions, both of pictorial documents, and of the original works of the great masters. The engravers supplied them. They did useful work, w'hich was often, incidentally, beautiful in itself.

Then came 'process'—the photographic reproduction first of line drawings, then of half-tones. The engravers were doomed. For a few years the American wood block makers smuggled heroically against ^he machines. But it was no good. "For all practical purposes there are now noi engravers. In a certain sense we have gained by their extermination. Pictorial documents of perfect accuracy can be made and multiplied with ease; the works of genuine, original artists can be reproduced by mechanical means, without having to pass through the refracting medium of the engraver's personality.

The labour which, in a happier age, they would have expended in the reproduction of Rubenses and Raphaels, in making steel engravings of Turner, in neatly scratching architecture, landscape, animals, figures on copper plates is now devoted to the playing of 'original' five finger exercises on canvas. No wonder, then, that the great' mass of modern painting is in general so appallingly dull.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now