Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSoliloquy

There Is Fine Sleighing on Main Street, but Where Are the Sleighs and the Horses?

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

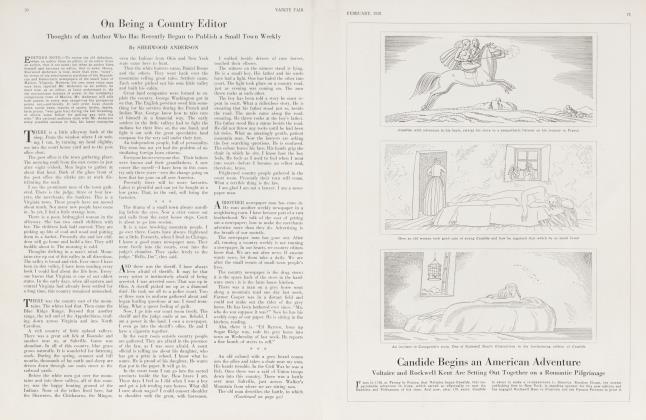

A FINE thick coat of snow over all of the roads—just the right sort—soft and clinging—not too soft.

The weather not too cold either. I have been keeping my eye on the road. Hasn't someone got somewhere a fine team of bays or blacks and a good cutter?

They used to make them with swans' heads sticking out in front. The runners stuck out behind so the boys could catch on.

It was a nice trick flipping a sled when it was hitched to a good fast team. Some young fellow in there with his girl—a buffalo robe tucked around her feet. A fine scheme was to heat a brick on the kitchen stove then put it in there, under her feet.

A grand racing time when sleighing came— up in Ohio. Now was the time to own a fast horse. They used to clear all the traffic off Main Street in our town. There wasn't much.

A man named Fred Harvey, with a big rangy sorrel, Frank Crosby, John Tichenor, Ben Heffner. Then there was Tom Whitehead. He owned a horse named Solarian, a big, fast black stallion. And Beverly Wall Stevenson with his horse, Bucephalus.

Doc Robinson had an insane mare. She was as fast as a streak—only she was crazy. You had to blindfold her or she would go right through the front of a store building. I wonder what makes females get like that sometimes?

ANYWAY, there they come. In my town they used to go up to the head of Main Street, a long, flat street. There weren't any hills to slide down. They went to the head of the street and turned. I can hear Frank Crosby whooping now. Frank had a cock eye. He had some nice profanity too. As a small boy I was always in love with fast horses. I can remember standing in front of the hardware store on a winter day and seeing those horses come. Solarian was in front with Doc Robinson's crazy mare just behind. Maybe Tom wasn't letting Solarian out for all he was worth. You got to be polite to a lady, even though she is crazy. Frank Crosby was laying in just behind with his fast little bay—a pretty little trick she was.

Will you look at Solarian come!

My own boy's heart beating fast. Tears used to come into my eyes sometimes—from just the joy of seeing them.

My God, why didn't I become a race horse driver? What's all this monkey business about being an author?

Nights, after seeing a horse like Solarian step, I would go home and to bed. Then I began to dream.

In my dreams I would be sitting up there with my hands on the reins. We were racing down Main Street over the snow or on the race track at the county fair in the fall.

There I was, sitting up there behind that horse, watching and watching. There was a big, free-gaited horse in front. A dozen other horses coming and coming, just at my back. All of us drivers were a little pale and tense.

Some of the drivers would be shouting and swearing too. Such a contest was not only between horses. It was between drivers too. It was something to be able to swear now. A good vocabulary was of some account. "Lay

over there, you -. I am coming right

over you if you don't lay over there and give me room."

"I'll give you room. I'll slash you across the face with this whip. You lay back there

where you belong, - you."

There I was in bed dreaming. We were getting near the end of the course. A little prayer going up now from between my clenched teeth.

IT was all a question of which horse had the most stuff, which driver had the most stuff. A weak-kneed driver always transmitted his own weakness to his horse. That was the reason the drivers had been swearing and cursing each other. It was a question of how much nerve a man had.

Bluff 'em out, if you can. That's the ticket. You make the hands of the driver tremble a little and bang—his horse goes off his stride.

Oh, I curse the day when all the fine trotters and pacers got swept out of everyday life. I tell you what, the pace of such a horse, when he is in full stride, is a delicate lovely thing to see—if you know anything about horses. It is as delicately adjusted as the flight of a bird.

But I was telling you about the dream of my boyhood. We were a poor family not able to own fine horses ourselves, not even enough beds to go around, so I was very likely sleeping with one of my brothers.

And now I was sitting up in bed, my whole body tense. My words rang through the silent house. "Easy boy. Easy boy. Now. Now. Now." I used to call like that in a high, falsetto voice. My brother slugged me in the ribs. "Ah, go to sleep, you nut."

Nothing there but the bare walls of the room, maybe the moonlight on the walls. I sank back and tried to sleep. What was the use of trying to sleep? Why didn't my brother leave me alone? When a fellow is in Paradise, why kick him out?

Well, there is something in a good automobile. I've had nights of driving. A clear, moonlit night and the road clear. No squealers on the back seat. If the road is a little risky, some bad sharp turns, it's all the better. You want a car that has a world of speed, a good pick-up. You want a car that has graceful lines. If I could have the car I want I would have a red racing car. They make them now— graceful and lovely enough. I've never been able to own such a car as I'd like. The millionaires own all the really fine ones.

Maybe I made a mistake not being a chauffeur. But I don't want any one giving me orders.

I could fit into the modern age if they would give me a chance. If I had a car like that and plenty of money in my pocket.

Wouldn't I go whisking about, seeking out strange corners in life?

You see in the days of the horse you could get a job taking care of a good one. Anyone can drive an automobile, even kids do it well enough, young high school girls. They go right into the stall where the car is and run it out. Well, there you are.

I'd have liked to see one of them go into Solarian s stall—or a horse I worked with once. His name was You-Be-Still. Let a stranger come into one of those fellows' stalls. I can see You-Be-Still rearing back, his teeth bared.

Or he'd whirl and kick you right through the barn door. I saw such a horse kill a man once.

Such a boy as I was could get a job with such a horse. Of course he didn't get paid much. Sometimes, when they were at the races, he and the horse had to sleep in the same stall. Well, it was all right. I'd rather sleep with a fine horse than with most people I know.

There was a chance to live a little poetry then.

What the hell—all this business of being an author. A lot of cheap little penny-a-liners carping at you. If you get your prose a little bare, like a horse's legs, a lot of old maids calling you "nasty", and other names like that. I never minded a race-horse driver swearing at me.

People talking about what motivates you, analyzing you. How the devil are they to know you are after the same thing you were after as a boy when you went to the races?

You want that feeling of life held up a little high, a little proud. What the hell, boys, let her ride.

Easy now. Sock it to her. There's your chance. You missed it, eh? Well, there goes your horse race.

AND there is something else about this mechanical age. I like to see a fine machine run as well as any man but there is too much loss of animal life tucked up close to human life. I suppose that is why tired out New Yorkers have the hunch about the negroes. They feel something in the smokes, animal life a little more alive, the rhythm and swing of animal life.

I remember nights when I was a boy and later as a young man when I had the blues. I have them yet of course; all decent people have them a lot nowadays. Safety first, eh? I had the blues and there was a horse somewhere about. I never got very far away. Many a night I've crept down into the horses' stalls, put my arms about their necks. Solarian, who would kill a stranger trying to come into his stall at night, would come and lay his head on my shoulder. He would let me hold his big head tight against my own until the blues passed.

And nights later, working on some farm. The big farm horses the same way. I remember one place where the man and woman of the house were always quarreling and jangling. I used to stand it as long as I could, sleeping in the house, and then get up and creep out to the barn.

Continued on page 102

Continued from page 58

How nice and quiet it was in there. I would go and touch the horses on the nose, rub the cows between the eyes. They liked that.

From the house the jangling voices. God help humanity when the animals are all gone.

What are we going to do, be authors, editors, millionaires?

All of this because snow lies thick on a village street. There is a long flat place where a horse could step. Nothing in sight but an old Ford, groaning and making a noise and a smell, the wheels whirling about.

No sound of sleigh bells in the air, no kids flipping bobs and sleighs.

No string of fast ones going up to tile head of the street, turning there, crowds gathered on the street. A shout. "Here they come!"

Hell, there isn't a good horse owned in this town and this is in Virginia too. Solarian rotting under the turf somewhere, no sons or daughters to carry on his speed at the trot and his good blood likely as not.

There are a few good hunting dogs about here, but in a few years the game will all be gone. Then you can't even see a good dog work.

I wouldn't care so much if I could really afford to own a fast, fine car. I'd like a sport model, painted red, but I don't want to be anybody's chauffeur. I wouldn't mind being a jockey again.

That would beat authoring or editing forty ways to the deuce.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now