Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNew Year's Day and Mr. Hoover

JAY FRANKLIN

A review of a crucial term in the White House; a glance at the future, while the New Year's handshakers file past

® The howls and wheezes of the latest electoral orgy have retreated far into the background. But we still have eyes on Mr. Hoover, whose days of presidential grace are fast ebbing out. It will soon he New Year's in the White House: the end of the Republican year, and virtually the beginning of the Democratic one. It ought to be a moment for many good resolutions. It surely will be a moment for many apologies. It is also the time to look back over the failures and successes of an Administration, just before it is ushered ofT into history.

Herbert Hoover was defeated for precisely the same reason that he was elected because he was not a politician. Endowed with one of the greatest administrative and organizing brains in the country, with a great record for competence, humanitarianism and practical achievement, he was elected by an unprecedented majority in 1928 because the people wanted something better than mere political manipulation in the White House. He served the country to the best of his ability and was defeated by an equally unprecedented majority, partly because his lack of familiarity with the political means necessary to accomplish the ends of statesmanship made him unable to meet the inordinate demands of the American system. The weight of the economic depression and the growing boredom of the electorate with a Party—and any Party—which had been in power for twelve years loaded the dice against him. A less scrupulous man might have made concessions and slipped through by a narrow margin, or, if defeated, have lost by a sufficiently narrow margin to save his political skin. The overwhelming character of President Hoover's defeat is a tribute to his determination and his character. He preferred to go down fighting for the principles which he had endorsed.

This is no paradoxical effort to draw flattering credit out of what must be to any man in the President's position a hitter disappointment. Nevertheless, the fact remains that Hoover dared to state his issues and to take a stand, knowing that lie was on the unpopular side, and to hack his own concept of conservatism and order against the intense popular demand for a change of pace in the Presidential sweepstakes. The last three weeks of campaigning, the fighting speeches, and the whole-hearted determination to define the issue as between himself and Roosevelt, somewhat rehabilitated the President in the public eye. Crowds which had booed him at the outset. often cheered him loudly at the close of his campaign. Even as the electorate voted down his policies, they applauded his pugnacity, and thus eliminated from the final rounds the sullen resentment and the angry ill-will which had accumulated during three years of hard times. Probably there were more Americans who respected Hoover as a man. at the close of the campaign, than at any previous time in his career. They approved of him. not as President, but as a human being; he appealed to the popular love of a good dog-fight, as he showed the country that he was not going to take the inexorable result of the election lying down, or to behave as a quitter.

So it is that President Hoover can face the New Year with a serene spirit. He has done his best in the face of catastrophic events. He had given the industrialists and the farmers protection through the Srnoot-Hawley Tariff. He had given to agriculture the Federal Farm Board, with its ambitious effort to create for the farmers economic agencies comparable to those enjoyed by Big Business. He had held up wages, prices and spirits after the collapse of the stock-market in October, 1929. He had extended Federal credit to relieve the drought-stricken areas in 1930. He had organized charity and "staggering" of work and shortening of hours for the relief of unemployment. He had resisted demands for bonuses and greenbacks. He had postponed a world-wide financial collapse by the moratorium of June, 1931. When England went off the gold standard in September, 1931, and when France began to withdraw her gold from the United States, he had bolstered our banks with the National Credit Association and its half billion dollar pool. He had replaced that emergency mobilization of credit with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and its §2,500.000,000 resources to support savings banks and life insurance companies. He had fought for a balanced budget. He had, in June and July of 1932, put additional resources at the disposal of the R.F.C. to relieve unemployment, to finance home owning and home building, and, through the Federal Land Bank system, to lighten the dangerous burden of farm mortgages. His foreign policy had been pacific and his domestic policy had been conservative. He stood for law— even for the Prohibition law—and for order— the traditional American order—during three and a half hard years.

B Unfortunately for him, he had to deal with an electorate which did not consist exclusively of statisticians, financiers, scientists, manufacturers or engineers, but of millions of perfectly undistinguished and human beings who were impatient for change and resentful of standpattism. Even so, the bankers, many of the big industrialists and the farmers did not appreciate the benefit of President Hoover's tariff: they wanted foreign loans repaid, special facilities for their exports or lower prices for manufactured goods. The farmers were resentful of the disastrous price-stabilizing experiments of the Farm Board. Investors caught short in the stockmarket wanted to get their margins hack. The drought-stricken farmers wanted immediate relief and no questions asked. The gold standard and its perils didn't arouse great popular enthusiasm, and the veterans resented President Hoover's drastic eviction of the bonus marchers. The spokesmen for the forgotten man complained that the R.F.C. loans were not trickling through to the masses hut were being utilized to buttress shaky credits or to supplant unsound collateral. Home owning and home building seemed less important than security against the immediate threat of eviction. Foreign policy didn't interest the man who had lost his job or whose bank refused to extend his note. People wanted to change or repeal Prohibition, not to enforce or obey it. Law and order didn't loom very large in the eyes of the ten million unemployed and their thirty million dependents or relatives. They kept their tongues and their tempers, and, when the time came, gave to the Democratic candidates a blank cheque on the nation's future.

This is an age of change, of vital experimentation and of necessary reconstruction. It was President Hoover's function to conduct the rear-guard action of conservatism against the forces of indiscriminate upheaval, and by his choice of ground for battle to determine the character and direction of the changes which he, and every intelligent member of his Party, knew were both necessary and inevitable.

B Furthermore, President Hoover has himself contributed powerfully to the actual and impending changes in this country. He has started more things than any President since Wilson. His Boulder Dam and St. Lawrence waterway projects have brought to the front, decisively, the issue of public ownership of hydroelectric utilities. The work goes forward and the issue ripens at one and the same time. His Moratorium of June. 1931, started a general diplomatic free-for-all. which promises to end debts and reparations, to revise the Treaty of Versailles and to unify Europe. His policy of refusing to recognize changes brought about by means contrary to the Kellogg-Briand Pact—applied initially to Japan's high-handed creation of a Manchuria independent of Chinese sovereignty—has brought within a single juridical conception the whole flock of Kilkenny cats of international law and order in a world based on war and disorder. Even his ill-fated farm measures have broken the ground for basic reform of the agricultural system of the United States. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation alone may well become the most powerful agency for effecting economic change in our national history. And finally, by the complete obliteration of traditional sectional and party lines, both in his election in 1928 and in his recent defeat, Hoover has made possible the complete reorganization and reorientation of both of our major political parties. His Cabinet, which, as is the custom on New Year's Day, will greet him in the Wrhite House, has included men of ability, character and distinction, in addition to the routine supply of party hacks and undistinguished competence.

Continued on page 62

(Continued from page 16)

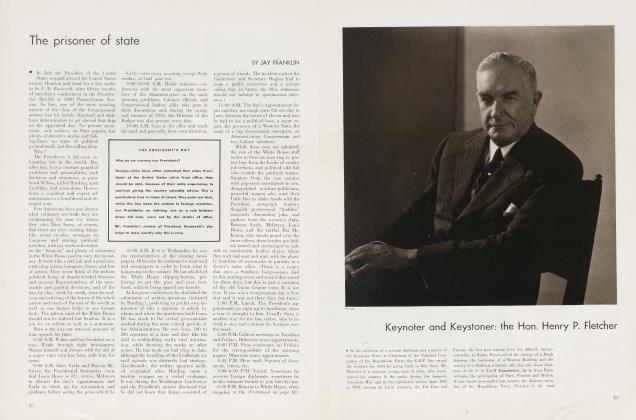

The Secretary of State, Henry I,. Stimson, is a man who has given the best of an excellent brain and of a world-wide experience to a thankless and difficult job. He has served without thought of personal advantage, selflessly and disinterestedly, for what he considered the public welfare. His views of Asia may have dated from Rudyard Kipling and his bearing towards his subordinates from the U. S. Army, but he has spent his energies and his fortune like water in wrestling with Latin American revolutions, war and rumors of war in the Far East, and change in Europe. lie did not try to use his office as a springhoard or a billboard. He has played the game.

The Secretary of the Treasury, Mr. Ogden Mills, has emerged as a brilliant, hard-hitting, shrewd and daring financier, administrator and politician. His management of the national finances during the depression has not prevented astronomic deficits hut has preserved the national credit unimpaired. His slashing oratory in the campaign has made him eligible for the next Republican nomination and has habituated the American electorate to the idea that a man of birth, culture and wealth can be as resourceful in politics as any machine boss.

Now it is time for a change of scene, a change of actors and a change of script. The country moves forward into a trying winter, the unemployed still file past the soup kitchens, and the national budget must still be balanced. No period in President Hoover's four years will demand so much courage, selflessness and patriotism as this Constitutional interregnum which defers the consequences of the election of November to the Inauguration four months later.

The President will be faced with the impatience of the victors for the control of policy and with the desertion of those of his own Party who prefer to face the rising, rather than the setting, sun. Grave problems of policy, affecting war debts, taxation, unemployment and Prohibition, to mention only a few of the obvious currents of contemporary politics, will demand urgent action by the President. He will he faced with the clamor of the huge flock of "lame ducks"—defeated Party leaders—demanding some form of appointive and permanent office. He will find some of the Democrats unwilling to promote remedial legislation lest the Republicans should thereby receive credit from the voters. And he will find some of the Republicans unwilling to join him in a policy of nonpartisan cooperation, for fear lest they will lose some trilling job or emolument. He will have a swarm of petty industrialists begging him for quickchange tariII protection and bankers urging upon him a policy of government borrowing. He will be forced to suffer in silence the swelling chorus of political obituary which began as the first returns rolled in on election night. And he will sense the great popular impatience for a new man and a new deal in the Executive Mansion.

It will require courage, character and patriotism to carry on wisely under these conditions. The country, however, which came to know him in the closing days of his campaign against impossible odds, feels confident that he is big enough to do it, to sink personal considerations and to put the nation before his Party. And he will have the comfort of knowing that the hatred and distrust which have dogged him for three years of national suffering have yielded to respect and sympathy for a President who had the strength to stick to his principles, when he knew that they were unpopular but felt that they were right.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now