Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

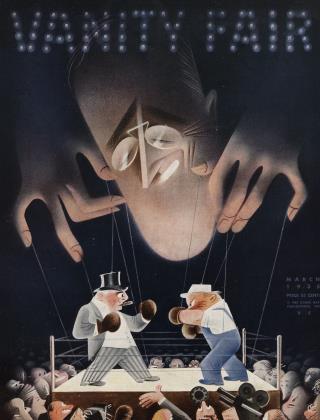

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBill Tilden and pro. tennis

JOHN R. TUNIS

Ten years ago, when Tilden defeated Johnston for the tennis title, Sam Hardy, a former Davis Cup captain, said in print: "To lovers of the amateur game, the thought of professional tennis is distinctly repugnant, but it may be that the public will in time demand its professional contests. Such a development is, however, a remote possibility."

That remote possibility has certainly come to pass. It is part of the times and if professional hockey, professional football, professional track and professional basketball are popular, why shouldn't tennis succeed professionally? Twice last season and once—so far—this season the Garden in New York has been a sell-out for tennis. When 15,500 persons pay $24,682 to see a match of tennis, when they stay until 12:30 in the morning to watch the finish of a doubles contest on which nothing whatsoever depends, there is no question of its catching on. Professional tennis is no longer on the defensive, it is here to stay. And, there is a place for it. On the whole, the quality of the tennis is higher than among the amateurs, certainly it will improve rapidly every year. Moreover, more people see the professionals, because the amateurs play almost entirely in tournaments along the Atlantic seaboard. O'Brien has taken the game into centers where they never saw good tennis before, he is popularizing it throughout the South and the Middle West, doing quite as much to stimulate interest in the sport there as the U. S. L. T. A.

Last season O'Brien's tour grossed $242,000. They played before nearly 200,000 spectators. Vines banked $62,500; Tilden and O'Brien, who share the profits with a 7525 split, divided the remainder of the net. They played 72 cities, this year 84 were booked. Stoefen and Lott will make about $10,000 to $12,000 this winter, while Tilden, O'Brien and Vines will share the proceeds after that. You can easily see where the money is coming from to meet the demands of the exigeant Mr. Fred Perry of London. The indefatigable efforts of O'Brien are another reason which makes me feel professional tennis is here for good. The Irishman with the streamlined jaw, who was working for $25 a week as a masseur in 1925, is now an established promoter with money in the bank, and with all the tennis players worth seeing except Perry and Von Cramm, the German, under his direction.

True, today Tilden is the chief armament of professional tennis. Where Tilden is, there is action, there is drama. He expounds the might, majesty and dominion of the art.

What is the secret of Tilden's hold on the game of tennis. There are many! But one of them is his energy.

As an example! We were sitting in the smoking room of the liner Champlain one sunny day last June over a bottle of Lanson, 1929. No one in his senses would drink champagne before lunch, but I'd drink anything to be able to listen to Martin Plaa, the French tennis professional. We were going to France and Plaa had just finished a three months' tour across America with Bill Tilden, and he was giving his impressions.

"Now, this type, Tilden," he began. "We travel all night on a train. Phew, your trains, your sleepings. We arrive, we descend in a hotel, we eat breakfast, and then, Vines, Cochet and myself, we go to bed. Tilden? Ah, no! He mounts in a car, visits three schools where he makes a discourse to the students, then he returns to the hotel for a luncheon of the Chamber of Commerce where he speaks before the business men. Afterward he goes to a bookstore and autographs his books for an hour, then he runs over to the armory where we play that night, arranges for the laying of the canvas, sees the lighting is perfect, settles a hundred details, submits to six or seven newspaper interviews, rushes back to the hotel, eats a quick dinner, and then jumps onto court with the three of us who have been resting in bed all day. And . . ." Martin Plaa leans forward and taps me on the knee, "and my old one, before his share of the proceeds, we are paid, we others, in full. Ah, c'est un phénoméne."

Ten years ago Tilden won the amateur tennis championship of the United States, defeating Johnston in five sets before the largest crowd that had seen a match in this country. Ellsworth Vines was then a boy of fourteen, Lester Stoefen had never touched a tennis racket, George Lott was shortstop on the Chicago University baseball team. Last month at Madison Square Garden, Tilden, giving away almost twenty years to the others, played a total of 109 games of singles and doubles between 8.30 and 12.30! After beating Lott 6-4, 7-5, he went onto the court with Vines to come from behind and conquer Lott and Stoefen 3-6, 14-16, 13-11, 8-6, 6-3. He found his best game toward the end of the doubles, and was in complete command, serving aces, smashing lobs and driving the ball with such speed that the former national doubles champions often failed to see it. When it was over he was the freshest of the four.

When he was champion back in 1925, Johnston was the next best tennis player in the world. Paul Berlenbach was light heavyweight champion, Cobb and Speaker were starring for Detroit and Cleveland, Bobby Jones had just won the Open, and Red Grange was running wild in the new double-decked stadium in Urbana. Johnston, Grange, Speaker, Cobb, where are they now? All his contemporaries have disappeared from the scene, Tilden remains, gaunt, alone. The others have vanished but his legs still carry him on and his brain still functions faster than any human brain in sport. Today at 43, in a young man's sport, he is still the prodigious artist who juggles with the years as well as with tennis balls. Give him two months rest and I believe that in a single match he would beat anyone, amateur or professional.

How is he able to outlast those who were champions a decade ago? He was pulling on his shirt in the dressing room in Madison Square Garden when I asked him that question. His face peered through the collar, eyes narrowed, then came the smile that has made history for 20 years. "Oh, you get used to it," he said.

The answer came directly and with emphasis. It didn't however convince me that it was true, "getting used to it" doesn't seem to answer the question at all. Vines, a younger man, for instance, couldn't do Tilden's work daily and play tennis. Bill O'Brien, their promoter, couldn't play as much tennis and do his work. They would crack under it. How can Tilden, who is nearly twenty years older than Vines, survive?

He carries on, I think, because playing tennis is fun for him. He is an exhibitionist, an actor, he loves crowds and loves to appear before them, but more than that he loves the game, the thrill of conflict, the fight for important points, the final surge, the victory. The best tennis I saw in 1934 was the finals of the outdoor professional championships in New York, when, at the end of a tour of 47 cities lasting 54 days, he was beaten by Vines 6-4 in the fifth set. It was more than a game of tennis, it was the eternal drama of youth and age.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now