Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Mind's Eye

TRISTAN VOX

Carl and Nora and Jack and Meryl

The secret is in a period of decline. It has been corrupted by its currency. One of the consequences of the media's marauding of American society is that the pleasures of gossip have become fewer than the indignities. It is beneath dignity, after all, to know the secrets of strangers. To be sure, the possession of a secret is a legitimate thrill of human association. And secrets are always premised on the existence of strangers. There must be a social division; it is the fact's forbiddenness to others that imparts its special delicacy. What all can know, none would want to.

But now all can know. American society used to consist of a collection of communities, each with its standards of excellence and its structure of rewards, within which information about those unknown to you had a specific meaning. The strangers whose secrets you learned still stood in some natural relation to you; they were of the same profession or the same church or the same sport or even only of the same place, people you might see and meet. No more. Now the grapevine is the size of the whole society. The work of the media has been to erase the social divisions that give gossip its edge. Now there are only two communities—the community of celebrity and the community of obscurity.

Celebrities begin their fame by being something, an actor or a businessman or a journalist—which is how fame in a society without an aristocracy of birth begins—but quickly they become famous for being themselves. They cannot long maintain the distinction between privacy and publicity. This culture makes the choice easy; it rewards the celebrity handsomely for his or her exhibitionism. The marketers of indiscretions are ready and resourceful, and the consumers of indiscretions are insatiable. Anybody's dirt can make it to anybody's kitchen. The media have tricked millions of people into thinking they are insiders. But of course there cannot be millions of insiders. In fact, if I know it, it cannot be a secret: this is the honest conclusion to draw about one's relation to privileged information in a frantically outer-directed society.

Which brings me to the person who has broken creative new ground in the cold and coarse use of the contemporary opportunities for gossip. A few years ago Nora Ephron (hereinafter referred to as The Wife) published Heartburn, a novel apparently designed to exact vengeance for the infidelity of Carl Bernstein (hereinafter referred to as The Husband). The book, which read as if it had been written by a wounded Joan Rivers, sold brilliantly on the strength of such drolleries as "the man is capable of having sex with a Venetian blind." In the course of her literaiy vengeance, The Wife reproduced for the reading masses all the moldy comers of her failure in love, all the dark little details of her marriage. It was a supreme example of the shamelessness of contemporary American self-promotion. The Wife correctly understood that if she was prepared to destroy her own dignity she could destroy The Husband's dignity, too. The price must have seemed worth paying while the mistress's sheets were still warm. Anyway, The Wife could count on a swift reduction in the price. What she would lose in dignity she would make up in celebrity.

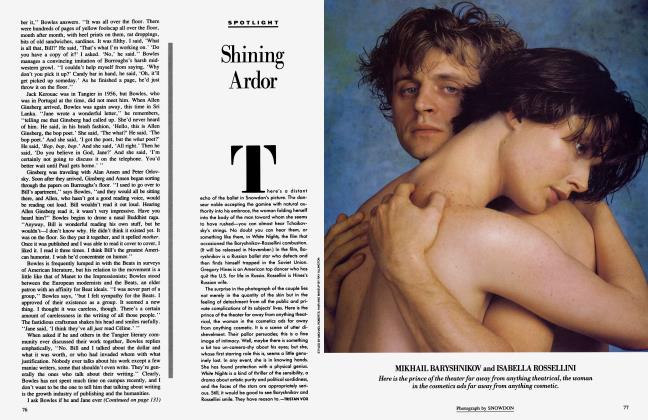

But hell hath no fury like a woman with an agent scorned. There is now to be a movie. It is well into production. Meryl Streep plays The Wife, Jack Nicholson plays The Husband. The director is Mike Nichols, the ultimate arbiter of urbanity. The screenwriter is Nora Ephron. A good time is guaranteed for all. And why not? Success with a movie often follows success with a book. Of course, it is worth noting that rarely has adultery been so kind to the cuckolded wife. The Husband's miscreancy turns out to have been a good career move for her. Still, she is arguably in the right. He betrayed her, and turning one's life into profits is the admired American way.

Except that The Husband and The Wife have children. And nobody is too young to be affected by a movie. What this means, concretely, is that one afternoon during their wonder years the children and all their friends will sit before a screen and watch their father be disgraced by their mother, and since the moral cognition of children is generally sound, they will watch their mother disgracing herself as well. They are the victims, the innocent victims, of her transactions. Is that a price too high to pay for the perquisites of further fame? The Husband protested that it is. The position of The Wife was a mystery until last May, when a protracted legal negotiation issued in a mutually acceptable agreement for settlement and divorce.

The agreement includes a rider called Attachment A. It is a document of intense anthropological importance; historians of American manners in the late twentieth century will make good use of it. Attachment A is about the delicate question of the children and the movie. In it The Wife graciously concedes to The Husband that he "will be portrayed at all times as a caring, loving and conscientious father," that he may provide her and Nichols with "written comments" after a careful reading of the screenplay, and that "any children of the major characters depicted in the movie will be female.'' (Presumably she thinks her own little boys will be fooled.)

Then there appears a sentence so incredible that it is difficult to believe that a mother could put her signature to it. (Or a father, for that matter; had she strayed and he written a book and a movie, the moral situation would be exactly the same.) "I am aware,'' The Wife admits, "that a movie based upon the Book raises the possibility of causing our children harm, however slight.'' Nothing less. It is followed by this: "It is my intention, as I am sure it is Carl's, that every reasonable effort will be made by both of us to avoid any detrimental effects or harm to our children from the Book and/or the Movie.'' Veiy clever, that affecting mention of "Carl.'' Unfortunately, Carl is not making the movie. Nora is.

In its friendly way, the Washington Post made The Husband look more hapless in its report of the settlement by suggesting that he had become a collaborator in his own vilification. The truth is that all the provisions for The Husband's power over the movie are meaningless. The power was, and is, The Wife's. It was her book and it is her movie. If her notarized concern for her children is genuine, there is still something that can be done. She can stop the movie, on the grounds that enough is enough. Otherwise, she will have authored not merely a novel and a script but one of the most indecent exploitations of celebrity in recent memory.

Of course, like all the new American gossip, the turpitude of The Husband was none of my business, or yours. The Wife, however, changed that. She created the book and the movie for the judgment of strangers. And so they will judge. About the book a moral ambiguity may linger; the woman was wronged. But not about the movie. The infidelity of a husband toward a wife is banal compared with the infidelity of a mother toward her children. Here is Carl Bernstein and adultery; there is Nora Ephron and child abuse. It is no contest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now