Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPlenty Good

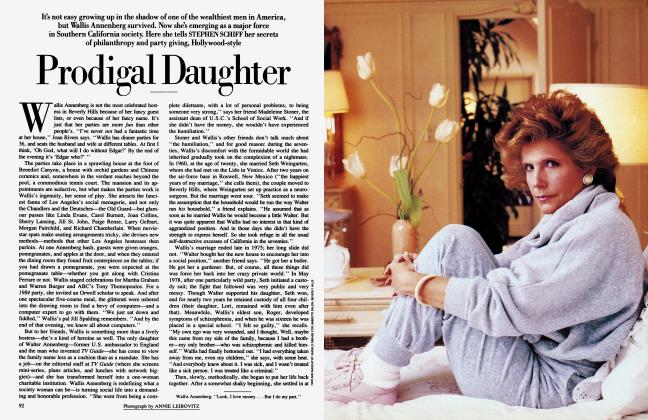

Stephen Schiff

MOVIES

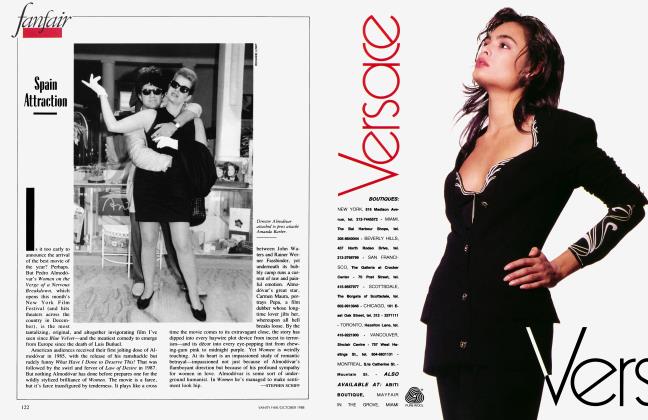

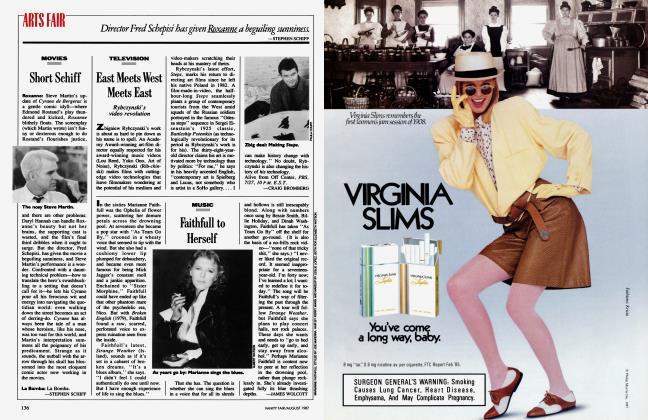

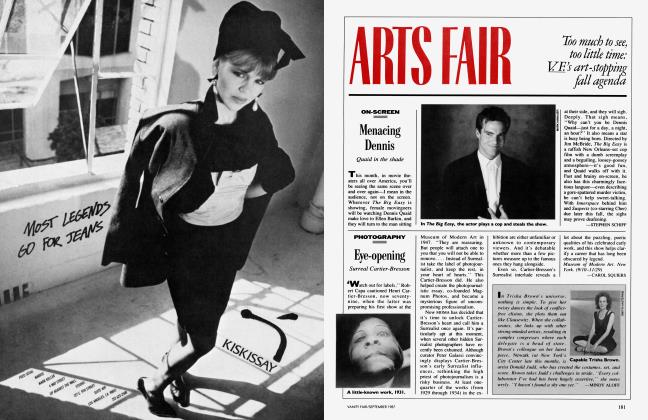

The great Australian director Fred Schepisi has done something wonderful with David Hare's hit play Plenty: he's made it bustle. Schepisi's movie version (from Hare's screenplay) is all charged entrances, huffy exits, forced marches down the corridors of power— it's a gabfest that feels as thrilling as an action picture. But Schepisi isn't just bulldozing a stodgy play to "open it up'' for the screen. His ripping and snorting echo the restlessness of Hare's ferocious protagonist, Susan Traherne (Meryl Streep), a sophisticated English scrapper who yearns to level the complacent walls enclosing her. For Susan, London during the prosperous fifties and early sixties seems fraudulent, unbearable. Where have the spunk and fervor of the war years gone? Susan can't stop daydreaming about the bravery, even the sensequickening terror, she experienced as a young Special Operations courier secreted in occupied France. And she can't stop mooning over Lazar (Sam Neill), the British agent who parachuted into her life for one incandescent night. "I know the signs,'' says Brock (Charles Dance), the foreign-service officer she eventually marries. "When you talk longingly about the war, some deception usually follows." Or some breakdown. Plenty is about how Susan wrecks her life and the lives of everyone around her in an attempt to recapture that evanescent sensation—the heady thrall of a cause.

"I intended to show the struggle of a heroine against a deceitful and emotionally stultified class," Hare has said of his play. And on Broadway that was the problem. Plenty the play was didactic and unpersuasive, mainly because you never saw much of the class Hare was railing against. Susan's noble anger was the whole show—especially since she was played by the fierce (and fiercely theatrical) Kate Nelligan. But in Schepisi's version, the world around Susan opens up; crowds swell; the screen feels fully inhabited. He and Hare have sliced away most of the play's rhetoric (though not, alas, the confusing transitions) and replaced it with detail. We don't have to be told that Susan's life as a foreign-service wifey is smothering her; here are the gloomy Persian carpets, the daunting mahogany, the gargoyle-like tchotchkes that hem her in. We're watching a biography, not a lecture on postwar ennui.

Schepisi may be the most underrated movie director now working: he captures the discourse between men and their landscapes more powerfully than any filmmaker since John Ford. Which is exactly what Plenty needed. Standing in the sunstruck meadows of France, Susan shoots out light beams; amid the comfy clutter of bohemian London, she's jivey and looselimbed; sitting on the committee for Queen Elizabeth's coronation, she wears drab suits and sensible shoes. She's a kind of actress, and Meryl Streep shows us how fervently this perfect chameleon longs to shed her skin and scamper away. It's an icily brilliant performance. Streep's Susan is no longer the fuming dragon of the stage production; she's softer and more vulnerable. There's a gorgeous moment near the beginning when, about to kiss Lazar, she hesitates, and then makes a swanlike swoop toward his mouth. She has considered caution and thrown it to the wind—and in one tiny stroke Streep has told us nearly everything about her. One quibble: as the character toughens and learns to hide, so does Streep. Her performance becomes crusty and grandiose—it begins to outwit itself. By then, however, it has accumulated enormous emotional power. When the film ends, we are no longer asking ourselves whether we approve of this woman. Streep has bonded us to her.

Meryl Streep shows us how fervently this perfect chameleon longs to shed her skin.

Susan is never very far from madness, and Hare views insanity as the British so often do—as a form of vivifying rebellion. Bemoaning their own infamous stuffiness, the English tend to admire bulls in china shops: destructive personalities may be impolite, but by God they have Life. Perhaps only an Australian director and an American actress could have weaned Plenty from such nonsense (which has never gone over big in nations where stuffiness is achieved only by the most rigorous application). Schepisi's Susan isn't a warrior against her class, she's a rebel without a cause, a woman who learned to time her life to the rhythms of war and now simply can't find the peacetime beat. Susan is a freak, a tweedy female Rambo, addicted to war the way men sometimes are —the way that no respectable English rose could afford to be. In Plenty, Schepisi has created something far more fascinating than any phony-profound folderol about repression amid bounty. He's created that rarity, an indelible character: a woman who can never stop beating the bushes for the enemy, can never stop expecting mystery lovers to drop from the skies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now