Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAvedon Goes West

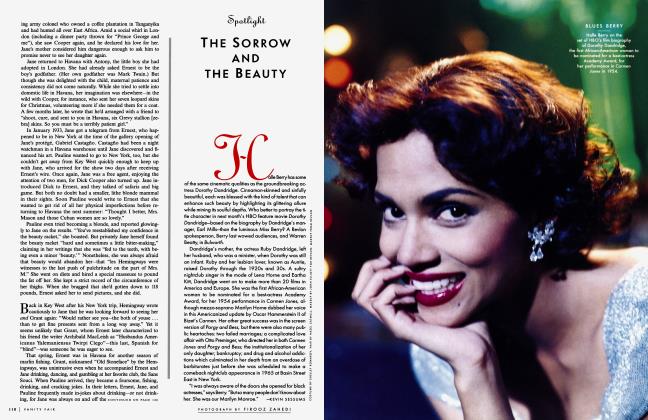

SPOTLIGHT

During the 1950s, Richard Avedon (restless, thoughtful, aspiring) lifted his eyes from the models and the fine clothes and went looking for America. Most recently, his search has yielded "In the American West," a traveling exhibition opening this month at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth. How far Avedon has journeyed. His first portraits were of performers, and he captured them this way: You are what you do so well. Before Avedon's camera, contralto Marian Anderson was all lips and lungs—one breathy song. Later, he got mean, or seemed to: noon-glint lighting revealed every wrinkle, pockmark, and sag. Dorothy Parker, Ezra Pound, Carson McCullers— Avedon inspected them, and found them terribly mortal. Time has softened Avedon's pictures. It now seems quite clear that he was never out to mythologize some and devastate others, but rather to assemble, like August Sander before him, a portrait of a nation.

In the last five years, Avedon has turned his gaze west, taking photographs in the Rockies and the Panhandle and on the plains, "going to truck stops, stockyards, walking through the crowds at a fair, looking for the faces I wanted to photograph." Among the 120 images that make up "In the American West"—a book will soon be available from Abrams—there are no portraits of Houston socialites, the Bass brothers, or the young chefs of Aspen, no faces of the New West. Nor of the old West or the wild West: Avedon now knows that his portraiture cannot create romance but can only reveal that which has been dashed. "In the American West" is not even about a place, really; the faces can be glimpsed throughout the country. Avedon has photographed those without place, hope, new frontier, or Manifest Destiny.

Drifters and camies, the unemployed and soon-to-be-phasedout, Avedon's subjects are on the fringes and in the shadows of a "postindustrial" America. And he refuses to condescend; there is no pity, no poetry, no second-rate sentiment. The white backdrops and mute-plain lighting banish all sense of time and place from the photographs—and why not? History, hurtling forward, fueled by progress, has sideswiped these Americans. And the slow, slow view-camera process has, as always, worn away that most resilient mask, the smile.

Avedon (wary, reflective, mild) calls these latest portraits an "opinion." He says, "None of them are truth." But g truth they are. The faces, placid in repose, have about them a freighted sadness that is not theirs alone. And in the best of the pictures—of nineyear-old B. J. Van Fleet of Ennis, Montana; of Wilbur Powell, the stolid, timeworn rancher—the eyes in these faces search beyond the camera's lens for contact with posterity: In this time, in this land, this is who we were.

GERALD MARZORATI

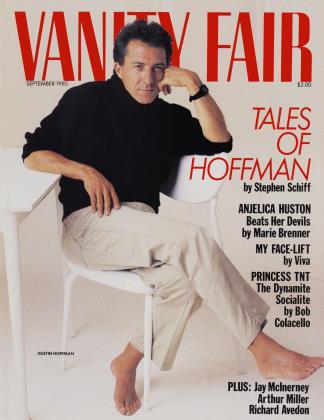

RICHARD AVEDON Avedon now knows that his portraiture cannot create romance but can only reveal that which has been dashed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now