Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHot Type

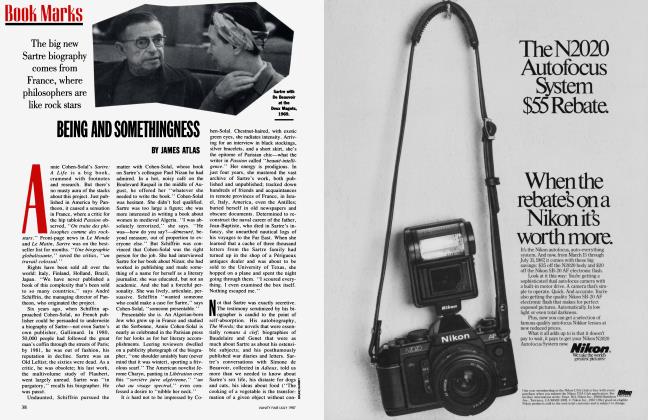

Eleanor and Stash are the sort of couple you might see at a party at Area. He's a successful young graffiti artist (who isn't?), and she's a rubber-and-plastic-jewelry designer. You've seen them. But Tama Janowitz knows them.

Slaves of New York (Crown) is a collection of stories—which passes rather nicely for a novel—written in a plain, dry, matter-of-fact prose. The voice is most often Eleanor's, and I don't remember when I've met such a depressingly dull individual before. But the interesting aspect of this uninteresting woman is that she is on the scene, part of New York's current, trendy downtown nightlife—the scene that is supposed to be excitement itself.

Only, no one in Slaves of New York seems to be having much fun. I was shocked. Until I realized that I don't have much fun either. The fashion models, artists, gallery owners—all disguised in the book—are just people who take showers, have parents, get upset stomachs, temporarily lose the will to live, and fall in and out of unfortunate relationships. "I'm madly in love," says one of Janowitz's characters. "It's so depressing." Even the pets here, mostly cats and dogs, are annoying, deranged, or crippled. But Slaves of New York grows on you, like a minutely detailed soap opera starring people you actually might know.

Stephen Saban

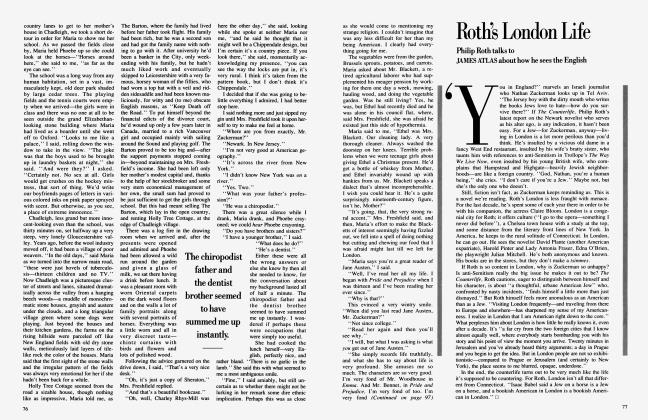

Elias Canetti is the Bulgarian-born playwright, novelist, and historian who in 1981 received the Nobel Prize in Literature. His life has found its most limpid expression in his memoirs, of which The Play of the Eyes (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) is the third and best volume. In it, Canetti describes his adventures as a young writer in Vienna on the eve of the Nazi invasion. He knew everyone: Alban Berg, Stefan Zweig, and Robert Musil all make brief (and often shockingly vivid) appearances.

Canetti is not only a charming memoirist but one whose very flaws become him. One of this volume's chief pleasures is its author's violent opinions: for instance, his scathing dismissal of psychoanalysis, and his ferocious caricatures of certain luminaries. (Of Alma Mahler's husband, the novelist Franz Werfel, he says, "His fat belly gurgled with love and feeling, one expected to find little puddles on the floor around him.")

Despite its occasional excesses of partisanship, this volume is a touching and often funny evocation of the period, enlivened by its author's gift for selfmockery and his grace as a miniaturist of both human frailty and human greatness.

Fernanda Eberstadt

Auberon Waugh, the waspish columnist for London's Spectator and son of Evelyn, deplores lesbians, old people, cripples, the poor. He finds toilet facilities for the disabled risible, and proposes that instead of issuing senior citizens discounts British Rail ought to charge the geezers more. A thoroughly disagreeable fellow, this Waugh.

Nothing is ever so simple. The voice that emerges from Brideshead Benighted (Little, Brown), a collection of Waugh's columns, is blunt, querulous, sarcastic, but somehow utterly engaging. A self-proclaimed "practitioner of the vituperative arts"—journalism— Waugh only masquerades as a curmudgeon. He may be a snob, but he spares no one his irony, not even himself. On a fact-finding mission to the slums of Liverpool, he reports: "My role has been to taunt the unemployed in pubs, lecture slum-dwellers in their pitiful homes . . . and generally make myself useful in an understanding of this delicate problem." So much for liberalism. On the important issues—religion, ethics, foreign policy—Waugh's true enemy is stupidity, of whatever ideological persuasion. "Genuine moral indignation is a rare and beautiful sight," he writes. Brideshead Benighted displays it in resplendent plumage.

James Atlas

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now