Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRAISING COEN

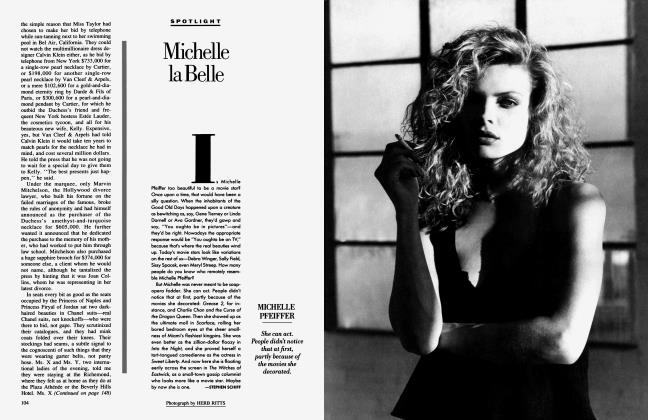

STEPHEN SCHIFF

Coen heads waiting for the brothers' follow-up to Blood Simple get a deliriously gabby comedy

Movies

Two years ago, when they were promoting their exhilarating thriller Blood Simple, the Coen brothers were like a droll heartland comedy team, bouncing wisecracks off each other with the deadpan aplomb that makes one a smash on the college circuit. Amid the ruck of studio movies, Blood Simple and its makers provided bracing refreshment. Here was a thriller so mischievous and funny and yet so gripping that it seemed to out-Hollywood Hollywood. And with it came this pair of movie-maniac wiseacres from suburban Minneapolis, a Penn & Teller who seemed to have swallowed the Zeitgeist whole; they were brainy without being cerebral, witty without being Saturday Night L/ve-spoofy; best of all, they knew how to tell a vigorous story and see right through it at the same time. All of which made them seem some supernal embodiment of Hipness Itself.

Now, as the ground swell builds beneath their second film, a rambunctiously charming comedy called Raising Arizona, one encounters a different pair of Coens. Terse, preoccupied, passing tense pauses back and forth as though they were gleaning secret messages from the ether, they've begun to resemble a pair of legendary autistic twins—like the eerie Poto and Cabengo, who shared a private language only they could understand, or like those bizarre brothers whom Oliver Sacks observed, the ones who conversed almost exclusively in prime numbers. Ask them about the origins of their new film. Or how they cooked up the plot about an ex-con, his barren police-officer wife, and their plan to kidnap one of the local millionaire's quintuplets and lovingly raise the child as their own. "Well, we didn't really. . .'' Joel will reply (he's thirty-two and does the directing), trailing off and then drawing on a Camel Light. His head will turn, ever so slightly, toward Ethan (who's twenty-nine and produces), and you'll wait a beat. Two beats. "Yeah," Ethan will say, sucking on his own Camel Light and staring out the window. "We really didn't..." And that will be that. Some obscure confirmation will have been exchanged between them, a question raised, contemplated, and silently dismissed.

You can't get the Coens to say much about their ostensible subjects—parenthood, lawlessness, life among the hicks—because they're not interested in themes, ideas, or trends. You can't get them to ponder their influences, because, although they love Preston Sturges, for instance, from whom much of Raising Arizona's abundant humor might have derived, they didn't once think of him as they made the film. So what do they want to talk about? Well, how great it was in Psycho II when Anthony Perkins hit someone over the head with a shovel in wide shot and the camera never cut away. Or how splendidly the voice-over works in the final scenes of Fellini's Roma. Or how hard it is to get a live lizard to sit still on a rock so that a nearby explosive charge can seem to blow him away. The Coens are like so many obsessive craftsmen, fluent and voluble on the minutiae of technique but inarticulate about the depths of their work. They seem to have left the real world behind, to have abandoned it for Movieland. "The truth is, the parenting theme didn't interest us much," says Joel. "We don't feel a special connection to it, any more than we did to murdering people when we made Blood Simple. I mean, I'm sort of fascinated with people killing each other, the way a lot of people are, and I'm sort of interested in babies, I guess, but nothing. . . " He trails off. A beat. Two beats.

"Yeah," says Ethan. "Nothing. . ."

s reticent as its makers have become, however, Raising Arizona is deliriously gabby. Its protagonist and narrator, a bom-to-lose thief named Hi (Nicolas Cage), has the cracker-barrel eloquence one finds in certain half-educated taxi drivers and TV preachers, and the Coens lovingly milk the contrast between the frantic goings-on we're watching and Hi's weirdly mellow narration. We see Hi scuttled off to jail and then paroled, only to rob and head for the hoosegow again; "I don't know how you come down on the incarceration question, whether it's for rehabilitation or revenge," his voice-over drones as we watch him scamper—gun and loot in hand—from yet another all-night store, "but I was beginning to think revenge is the only argument makes any sense." One grows to like poor Hi; the more he cowers behind his byzantine locutions— "I preminisced no return to the salad days," he moans—the more vulnerable and exposed he seems. The composer Carter Burwell has concocted a wonderful theme that yodels on the sound track like a woebegone dogie; its scooting banjos evoke a Wild West of sweetsouled outlaws who yearn to be good but just can't seem to stay out of trouble—must be an ornery streak in 'em somewheres. Or, as Hi's voice-over puts it when childlessness gets him down: "The pizzazz had gone out of our lives. . .1 even caught myself drivin' by convenience stores that weren't on the way home."

The sound track's scooting banjos evoke a Wild West of sweet-souled outlaws who just can't stay out of trouble.

Raising Arizona's, plot isn't as keenly honed as Blood Simple's', it clatters down the lonesome Arizona highways, belching fire and leaving shards of fender in its wake. There's no shapeliness or suspense to speak of, there are far too many feverish chases, and there's an awful lot of what Joel Coen calls "the sounds of male bonding"—bellowing, to you. But the movie feels warm-spirited and generous; every frame bulges with props, in-jokes, and asides, in the manner of those teeming movie parodies the cartoonist Mort Drucker used to draw for Mad magazine (a Coen favorite). The brothers seem to be having a ball, and inviting crashers. If the characters are jailbirds and lowlifes, they nevertheless have the winsomeness of

the featherweight romantics in a Renoir or Jonathan Demme film. When a pair of ugly galoots named Gale (John Goodman) and Evelle (William Forsythe) escape from prison and hide out in Hi's mobile home, the Coens play their bust-out as a birth scene. The big lugs come twisting and howling through a hole in the muddy earth on the dankest night of the year, and from the moment they emerge they seem at once fearsome and oddly cuddly. Like almost everybody else in the movie, they're just big babies.

To the Coens, in fact, the rural Southwest of Raising Arizona is a landscape of incorruptible innocence. Their movie joins Blue Velvet, Something Wild, True Stories, and others in the It's a Wonderful Life sweepstakes. It's part of the movies' burgeoning interest in a new sort of exoticism: the foreignness of American life between the coasts, away from the cities, in the cast-in-amber never-never land of small town and countryside. The yuppies who make movies and the yuppies (and their children) who see them have become so removed from the poky, traditional universe that used to be called the backbone of America that life there suddenly seems a mesmerizing novelty, at once incomprehensible and strangely familiar, us and not us. The questions behind even the most boisterous of these movies are the questions earlier, immigrant generations asked themselves about the European motherland: What have we given up? What have we escaped? And what of that forgotten world resides in us still?

I oel and Ethan call this "The Hayseed I Renaissance." ("We don't much 3 care about that, though," Joel insists. "In fact, I'm pretty tired of it." A beat. Two beats. "Yeah," says Ethan.) Raising Arizona is like a True Stories that doesn't protest so much. Whereas David Byrne's movie pokes fun at its Texas hicks and then bends over backward to tell us it really admires them, Raising Arizona blasts off from the premise that hicks are a sure goof, that middle-American gewgaws and mores and speech patterns are the sophisticated American's version of a Polack joke. The movie is a riot of Barcaloungers and polyester and supermarket colors; every pimply clerk in every store carries an enormous gun. But this isn't a parody; the humor comes from the characters, not from the redneck kitsch. Once we're laughing, the Coens let their affection seep in, and soon the movie is saturated with it. In the garrulous Hi and his fierce little wife, Ed (Holly Hunter), in Gale and Evelle and even Nathan Arizona, the unpainted-furniture tycoon whose fifth quintuplet Hi steals—in these broadly sketched figures the Coens find a wistful and redeeming childishness; they've created a universe of ageless dreamers. Only the wanton biker, Lenny (Randall "Tex" Cobb), who's stalking Hi because he wants to steal the kidnapped baby for the reward money, seems truly grownup and truly villainous. And I think his inclusion is a mistake. He reminds me of the fire-breathing behemoths that movies like Howard the Duck and The Golden Child order up from the George Lucas factory when they need a spectacular climax.

Raising Arizona is a riot of Barcaloungers and polyester; every pimply clerk in every store carries an enormous gun.

Still, Lenny and his Harley from hell create the occasion for some amazing shots, and when the Coens are at their best, their camerawork dazzles. It hurtles exuberantly through streets and alleys, leaps over fountains, cranes back in amazement. Self-conscious without being precious, Raising Arizona is always pointing at itself, at its own "movieness," and there's scarcely a shot in it that doesn't look tricky. Often the tricks provide an invigorating lucidity; the details the camera shoves at us seem fresh, illuminating. But during the long chase scenes, when everything is pitched at the same industrial roar, the movie can be annoying. The Coens seem to be grabbing your head between their hands and pointing it at the things they want you to see—and you may feel like shaking loose from time to time.

Especially when you find your face thrust into Nicolas Cage's. The Coens aren't yet expert directors of acting, and Cage is a hound dog who could use a trainer. He's fine, even touching in the quiet scenes, but he gnashes his way through the action stuff, squinting, shuddering, and popping his eyes.

And here is where one feels the Coens may need to pull their heads out of the Movieland loam and take a gander at the real world again. For there is enough subtlety of feeling, enough real poignancy, in Raising Arizona to make one believe that the Coens could easily have gone further—could have made not just a buoyant amusement but a great movie. Without sacrificing the jubilant comic spirit and the licketysplit pace, without sacrificing even the technical pranks, they could have explored the themes they so deftly graze: parenthood, yes, and also the lure of criminality, and the peculiar quality of rural innocence. To do so, of course, they might have had to expose a little of themselves, to put not just their best gags on film but the whole of their personalities. And that, they're clearly in no mood to try. If you tell them they have what it takes to move from the realm of extraordinary craftsmanship into the realm of art, they'll just smirk at you. "I feel like things either work or don't work," Ethan will say. "You take two big guys like Gale and Evelle squeezed into a little car, blubbering— and what's not to like?" A beat. Two beats. And Joel will say, "Yeah." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now