Sign In to Your Account

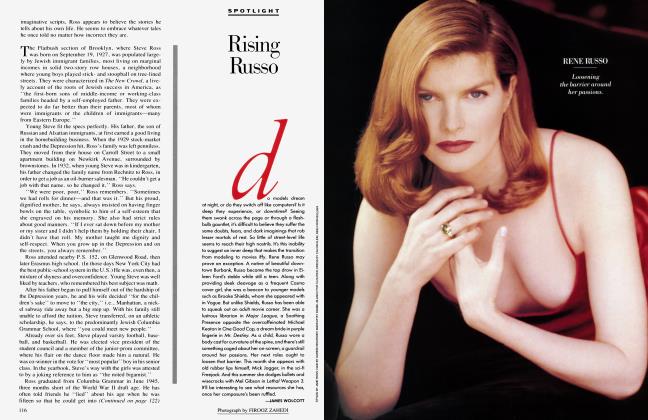

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEAST OF LONDON

The lower depths of Thatcher's England on EastEnders, PBS's Cockney cult show

Mixed Media

JAMES WOLCOTT

Charles and Sebastian boating on the lazy river in Brideshead Revisited, Lord and Lady Bellamy beaming across a banquet table in Upstairs, Downstairs—sink 'em, burn 'em. What's posh is past. For too long on publie television its English imports have been gala reports from the rear on the loss of empire. Wedding-cake couples with names like Clive and Cecily barely spill a drop of champagne as bad news drifts in from distant outposts. The forced gaiety on the actors' faces is a gallant stand against gloom. Acting itself becomes an aristocratic holdout to class erosion at home and rising nationalism abroad. The empire may have crumbled, we're supposed to marvel, but English actors, how they enunciate.

No one will ever salute the cast of EastEnders on their silky address. They speak with spiked tongues. An inspired Cockney version of a George Booth cartoon, EastEnders situates its characters in tenements suffering from thin walls and insufficient light. Like Booth's bathtub philosophers, these blabbers are physically worn down but eccentrically wound up. Peculiarities pop out of their heads like springs on a bum mattress. Shown nationally on public-television stations (check local listings), EastEnders is everything an English import series isn't supposed to be—newsy rather than nostalgic, weedy rather than flowery, lower-cruddy rather than upper-crusty, colloquial rather than epigrammatic. Because it doesn't blow a rich note of requiem, it hasn't become a cultural event like Brideshead Revisited. But it has hooked a hard-core faithful. We happy few!

Created by Julia Smith and Tony Holland, EastEnders first hit the airwaves in England in 1985. It was an instant monster. Audiences took to it as if it had been sitting in the hangar all their lives. And in a sense it had. Set on Albert Square in London's East End (Albert Square—a made-up locale that has become mythically real), EastEnders concentrates much of its noise in a pub called the Queen Victoria. On tap at the Queen Vic is a brand of brew called Churchill. Churchill's logo lines the bar. The names establish a historical bloodline. Queen Victoria: the essential unchangeable England, its ample, moral bottom enthroned upon the globe. Churchill: England under siege, bearing up under night raids and bomb rubble.

So even before the first pint was poured at the Queen Vic, EastEnders had dusted the air and woodwork with doughty tradition. But none of these aging touches would have counted for aught if the show didn't carry a contemporary kick. Did it ever. The opening shot of the series was of a door being kicked in by a size 10 boot. Behind the dented door is a stiff old sod named Reg Cox making his first and only appearance in the series as a frozen fish stick. The removal of his cold carcass clears room for one of the changes coming to Albert Square. Moving into Reg's vacant flat is Mary (Linda Davidson), an unwed punkette mother. She's a sight. With her snarling beak and ghoulish black eyeliner, Mary is an electrojab of future shock. Like brief glimpses of sun, sweetness peeps through her fright mask.

Mary is one of many on the passing scene. The traffic round Albert Square is thick—a human moat tough for some viewers to bridge. To Americans the characters' insular slang and serrated diction make their dialogue difficult to suss. (Public television offers its subscribers an EastEnders glossary, which explains such words as, well, "suss.") Virgin viewers have also been known to suffer brain cramp trying to figure out the family arrangements at Albert Square. (Cramps also buckled some critics' brows. When Emily Prager panned EastEnders in The Village Voice, she managed to garble nearly every damn detail.) But as long as one remembers that the Queen Vic is the mother ship of the show, one really doesn't need the mellow M.C. stylings of Alistair Cooke for orientation. Eavesdropping on the conversations there assists in cracking the show's code. Sopping up the atmosphere helps too. Not that EastEnders ever totally forfeits its foreignness—for us, Cockney remains another country. Describing a long stay in London, the critic Seymour Krim claimed that we Americans see the Brits through the slits of our robot skulls. "Efficiency is our Second Self. . .but the extent to which we are obsessed by machines who love other machines can never be known until we leave the States and walk smack into rust and bathroomfloor overflow.'' Rust never sleeps on EastEnders, where bathroom-floor overflow often plagues the Queen Vic.

Up to his ankles in spill is the Queen Vic's manager, Den Watts. Played with roving stealth by Leslie Grantham, "Dirty'' Den (the English tabloid press bestowed the epithet) is the show's most roguish wolf of libido. He knifes into every scene as if there might be meat at the end of the scent. His roving has his -wife, Angie, raving. Red of hair and nail, Angie (Anita Dobson) is the Maggie the Cat of the show, pacing a cold tile floor rather than a hot tin roof. Their adopted daughter, Sharon (Letitia Dean), is a no-torso, no-neck blond howitzer shell—a Samantha Fox sexual projectile. Sharon is Den's precious snookums. But even Sharon drops him like a stinky sock when he tries to divorce Angie to marry his mistress, Jan (Jane How). Jan, who seems to have had a nostril implant from Betrayal's Patricia Hodge, exhales thin, worried, cultured streams of equivocation. She frets; she sighs; she clasps Den's hands. Exquisitely coiffed, Jan has a strategically placed scarf draped over every outfit as an emblem of savoir faire. She seems to have acquired her toniness from adulterous novels by Margaret Drabble or Fay Weldon. Against such aquiline airs, who wouldn't root for Angie the cat?

This is not like Dynasty, where the catfights are conducted with Lee Press-On claws.

Romantic rivalries such as the DenAngie-Jan triangle are rare on EastEnders. Most of the drama derives from the sheer effort to stay solvent. For East Enders, it's a short stroll from our house to the poorhouse, a stroll lined with shame. One of EastEnders' most uncompromising story lines concerns the self-administered skinning alive of Arthur Fowler (Bill Treacher) afterhe becomes unemployed. A discard of the system, Arthur can't cope with desperation. He feels bad enough being a lump at home. When he is caught stealing money from his mates' Christmas-club fund, his shame is compounded. Useless, unshaven, he wanders around the living room in a ratty bathrobe, looking unbathed. His watery eyes recede. Shaken by this sorry sight, his bedrock wife, Pauline (Wendy Richard), pleads with him to pull his socks up. "Pull yer socks up, Arfur." He plants a bare foot on the table. "Well, I'm not wearing inny socks, em I?" She buys him a pair of socks, him like a schoolboy: "Arfur, put on your socks, Arfur." Fast becoming fungus, Arthur hides in the garden shed to have his nervous breakdown in peace. He's soon forced to vegetate in hospital, doped to the gills. "Poor Arfur," laments Pauline. A less exacting story line had Pauline's sister-in-law, Kathy (Gillian Taylforth), sweating out a deadline for a shipment of homemade sweaters. The crook who commissioned the shipment finds himself whaled against the railing of Albert Square. Such strains are a far cry from the corporate-jet, earphone wheeling-dealing of Dallas and Dynasty—yet more involving, because this cry issues from the bare cupboard of human want and not from the deep closets of the wardrobe department.

It isn't all toil and trouble in the ragand-bone shop of the heart. There are humorous regulars on the razzle round Albert Square, none of them "cor, blimey!" Cockney stereotypes. There's Kathy's son, Ian (Adam Woodyatt), who has the eyebrows and auburn coloring of a younger Martin Amis. Always napping on some sofa, Ian answers his wake-up calls by wiping the clouds from his blurred cheeks and then, reunited with the world, staggering into the bathroom wrapped in a blanket. (In one scene the characters converse for minutes before his head emerges from its woolen cocoon. Until that moment we didn't even know he was in the room.) The mellifluous Mr. Slick of the show is James Willmott-Brown (William Boyde), who's a chilled white wine amid all these beery lads—smooth, with just an amusing hint of presumption. There's a gay couple, Colin (Michael Cashman) and Barry (Gary Hailes), whose aesthetic taste buds clash. Colin is austere and retentive, Barry gaudy and brash. The Christmas decorations Barry hangs in Colin's flat (holly and tinsel by the handfuls) have Colin whitening round the eyeballs.

Sitting in constant judgment at the Laundromat is a chorus of old crows with their own odd grace notes. Dot (June Brown) is usually the first one to put in her tuppence. Cigarette in hand, she puffs pieties under her protruding teeth. Her frail health has made her reflective: "I was always a sickly child; I think I heard the angels once." A hilarious blend of hypochondria and nosiness, Dot has many a cross to bear. Her son is a hoodlum, her husband a sponging cheat. Spotting Dot entering the Queen Vic, her husband blurts to the barmaid, "Oops, enemy gunboat in sight.'' (Dot's ideal husband would be Floyd the barber on The Andy Griffith Show—her unctuous equal.) Potty and potted Ethel (Gretchen Franklin) with her pug dog is also a hoot. The humor is not incidental. Sometimes even in Dickens and Shakespeare comic relief brings a break in the action when the foibles of their characters become fustian. Not here. The comedy comes along for the rat-a-tat ride like a baseball card flapping against a bike wheel. The fast, efficient writing and editing keep the spokes spinning toward a larger aim.

If EastEnders has a charter, it is, according to its creators, "to be fast-moving, tough, and firmly rooted in the 'eighties, set uncompromisingly in Thatcher's Britain.'' On stage and screen, "Thatcher's Britain'' usually translates into a soulless slide into chauvinism and materialism overseen by Supemanny. Smug nannykins appear in such movies as High Hopes, by Mike Leigh, and David Hare's Paris by Night. (Hare's play The Secret Rapture also features a Thatcherite.) Sammy and Rosie Get Laid depicted Thatcher's Britain as a blazing theme park. EastEnders resists the temptation to turn Maggie Thatcher into Mommie Dearest. It also resists the impulse to let her detractors hog all the finer feelings. (Unlike, say, High Hopes, where only the socialist couple is allowed expressive shadings— everyone else is a shrill cartoon.) EastEnders doesn't resort to visual or verbal editorializing to ensure a correct response. The show is character-driven. To one, Thatcherism is a spur to success; to another, a stress test. Crawling with energy, EastEnders is what the critic Manny Farber called termite art: its characters cheerfully, subversively chew away at the boundaries of their condition. It's only when one watches the series for a stretch that the larger contours of its sexual and racial convictions become clear.

Sexually, EastEnders is implicitly feminist. Its women are made of hardier material than its men. (Excluding Den.) The women are a snappish lot. A walking apology like Lofty (Tom Watt) wanders around without a clue as his wife, Michelle (Susan Tully), refers to him as "birdbrain." The cafe owner, Ali (Nejdet Salih), is no match for his spitfire spouse, Sue (Sandy Ratcliff). Sometimes the implicit feminism becomes explicit. When an attacker roughs up women in the area (and it's to the show's credit that, unlike daytime soaps over here, it didn't shoot the assaults from the stalker's point of view, enlisting the viewers as voyeuristic accomplices), Sue explodes over the restrictions men levy on women's lives. "Why should we be under curfew, afraid to go out at night? Men should be under curfew. It's them that does this to us." Not that sisterhood is always powerful on Albert Square. The women take it to the men and take it to each other. One night at the cafe Sue has a knock-down-dragout with Mary. Git out, ya cow! And when Mary unshrewdly tries to turn street pro, hardened hookers rake her face, the scratch marks warning her not to poach on their turf. Again, this is not like Dynasty, where the catfights are conducted with Lee Press-On claws. Serious survival is at stake.

The racial minorities tangle too. The West Indian cabbie Tony (Oscar James) has no use for the Bengali shopkeeper Naima (Shreela Ghosh). The merit of the show's melting-pot approach is that it doesn't equate racial and sexual politics. It recognizes separate spheres. In the radical-chic Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, for example, interracial relations were locked at the loins—sex was the great desegregator. On EastEnders, ethnicity isn't an orgone box for the body politic. Tensions and attractions between the races are thrashed out instance by instance rather than emulsified in some mutual meltdown. White and black alike link arms to bash the barrel staves out of the bastard who ripped off Kathy's sweaters. The hubbub of the street and not the bounce of the bed is where it all happens.

As if to demonstrate how a racially mixed show shouldn't be done, NBC has launched a new daytime soap called Generations. It's about two families—one white, one black—straining to read the TelePrompTer on studio sets that look like sets. The star of Generations is Taurean Blacque, so strong and understated on Hill Street Blues as the cop keeping tabs on Kiel Martin's J.D. On Generations he's reduced to chuckling wisely to himself to camouflage the dead spaces in his characterization. He plays an ice-cream magnate, which is apt, since race relations on Generations consists of alternating scoops of chocolate and vanilla. Unlike EastEnders, the show has no grit or push. It's all glassy, gutless emoting. Its women luxuriate in their skin tone and what it means to be an Actress. Its men luxuriate in their skin tone and what it means to be a Hunk. But they speak the same language, or at least the same dip-head dialogue. "Don't cut your nose off, if you can catch my drift; every cloud has a silver lining, and if anyone's gonna find it, you will," says a gooey vanilla Actress to a moody chocolate Hunk. He leaves the room. Who can blame him? He had to wipe egg off his face. I suppose a case can be made for Generations' being camp: so-bad-it's-good, etc. But EastEnders uncultivates one's taste for camp. It makes you want more of its bitter charge. EastEnders cauterizes— bums away the blah. What's left is hard, tempered, resistant, funny, and real.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now