Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

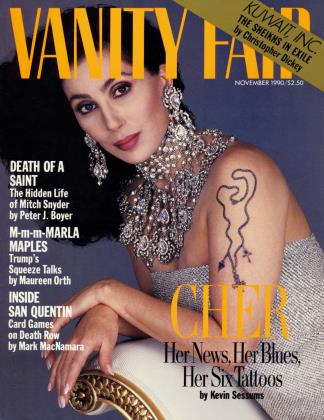

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMAN OF THE MOMA

MARK STEVENS

Curator Kirk Varnedoe, the Museum of Modern Art's star acquisition, is poised to take it into the next century with his "High and Low" show

Art

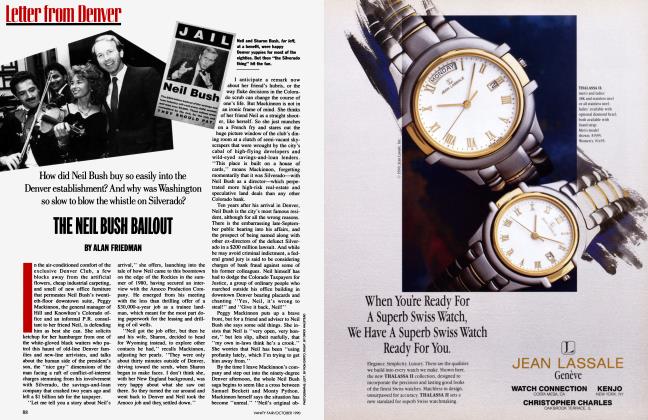

Soon after he was appointed the new director of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modem Art, still the most powerful job of its kind in the world, Kirk Varnedoe wheeled a trolley into a meeting of an acquisitions committee of the museum's board of trustees. On the trolley was a concealed object. Vamedoe let everyone enjoy the drama of the moment, then pulled off the cover—revealing Robert Rauschenberg's famous Bed of 1955. The work was a critical addition to the museum's collection, but that was not what created the feeling of presto! The miracle, at a time when the art world has become a symbol of shameless self-promotion and trashy excess, was that this was a gift.

Leo Castelli could have sold the work privately for about $9 or $10 million; it might have fetched far more at auction. Instead, he gave the Rauschenberg to the museum because it finally meant more to him than money. He made the gift in the memory of Alfred H. Barr Jr. (19021981), the legendary founding director of MOMA, who embodied the conviction that the art of one's own time deserves the same rigorous attention as the art of the past. Under Barr's stewardship MOMA became an institution that, without acting like a cultural nanny, symbolized the highest values of both art and philanthropy.

It will now be up to Kirk Vamedoe, who was appointed in 1988, to maintain that complicated spirit. The small moment with the Rauschenberg reflects the hopes placed in the new curator. He is supposed to collect and exhibit art with panache, while not sacrificing the standard set by the past. He must do so knowing that MOMA is no longer the small and aristocratic place full of missionary zeal that Barr created. Museums have become big-time bureaucracies, and modernism itself has aged, losing some momentum. For the Museum of Modem Art, which is to modernism what Rome is to Catholicism, the eternal temptation will be to retire into its history, honing its collection and refining its dogmas.

In his monumental shows celebrating the great artists, themes, and moments of modernism, William Rubin, Vamedoe's predecessor, brought a stately, commemorative spirit to the museum. By appointing Vamedoe, who likes recent art more than Rubin does, MOMA is trying to pull off a neat trick—to become younger while growing old. Vamedoe's beguiling way with words, together with his gift for approaching art in many different ways, has aroused the hope that he can transcend the paradoxes of an aging museum of the modem during a period of rampant vulgarity.

"In the standard dilemma of our day the choice is supposed to be between pleasing the public and doing serious shows," he says. "I don't think that's a problem. If you can do it right, you don't have to compromise either thing. ' ' One of his friends calls Vamedoe "a consumable character. As somebody whose job has public impact he'll be terrific. He can be popular without being vulgar."

Vamedoe has won a MacArthur Fellowship, he is an admired art historian, and he is forty-four, handsome, and more articulate than anyone has a right to be, speaking with a rich baritone voice that comes stirred with a little southern honey. He has been so successful, in short, that many people naturally' assume the worst.

A man like that is often just an excellent apple-polisher who displays no troublesome originality and gets along by going along. What's intriguing about Vamedoe—what promises to make his years at the Modem significant—is that he does not seem interested in settling down now that he has "arrived." Varnedoe is a man in love with the unpredictable liveliness of modem art, with its variety and questing spirit. "One of the things I admired about my teacher at Williams, Lane Faison, was that he liked paintings that were huge and aggressive and boisterous and fleshy and romantic," Vamedoe says, piling up his adjectives with characteristic relish. "But he also had a wonderful feeling for Vermeer and things that were quiet. He helped me leam about flexibility and tolerance, about the qualities that reside in different things." Perhaps that is why, in his first major show, Varnedoe has taken such a remarkable risk.

Not many people in the art world know what a nose tackle is. Varnedoe actually was one.

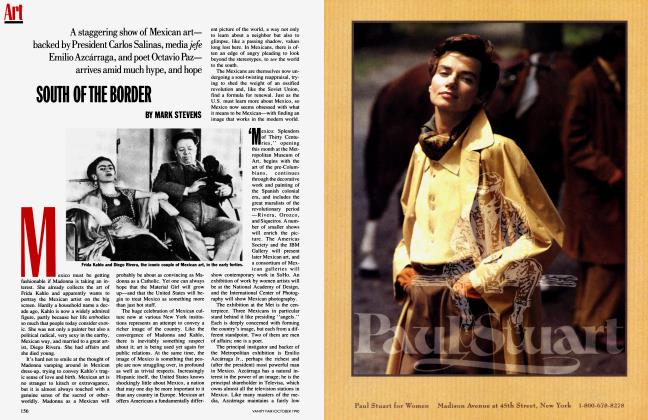

A smart apple-polisher would have begun with a big safe show on a big safe artist. In the exhibition opening this month, Vamedoe has instead chosen to address the single most controversial theme of his day. "High and Low: Modem Art and Popular Culture"—a collaboration between Vamedoe and his former student Adam Gopnik, now a staff writer and art critic at The New Yorker—examines the rich interplay between serious art and mass culture in modernism. The broad outlines, of course, are well known: Leger studied billboards, the Cubists clipped newspapers, Pop artists looked at cartoons, and so on. The MOMA exhibition intends a detailed look at the relations between high art and advertising, graffiti, and comics.

For ideological reasons, critics from both the left and right are obsessed with the high-low theme, as are many contemporary artists who make use of popular media. Some critics have attacked the show even before reading and evaluating the catalogue or studying how the work is presented. Conservatives worry that the aesthetic values of serious art, as evidenced by MOMA'S traditional connoisseurship, will be diminished if high art is not forcefully distinguished from pop stuff. They fear that MOMA will reduce art to just its ideas and iconography. Many on the left, in turn, regard separating high and low as elitist, the old formalist rhetoric in a trendy guise. Varnedoe insists without apology upon the distinguishing value of high art, but sees no reason to give mass culture the back of his hand. "The show is not about kitsch. It's not about debased high art or arty low art. It's about things that are truly different, but still have this incredible ping-pong back and forth. There may be people who wish that this weren't true, that art were produced in lofty towers out of high and purethoughts, but if you admire Miro, Dubuffet, Guston, Picasso, Twombly, you have to admit that one of the major sources of their energy, part of what makes them wonderful, is precisely an openness to these sources."

Vamedoe has the MOMA job partly because he himself embodies many of the paradoxes that nowadays bedevil an aristocratic institution. He is a person who knows high and low, personally.

While not wealthy, Vamedoe comes from a prominent Savannah family (his grandfather was mayor of the city). His father was a stockbroker, his mother a woman with an enlightened interest in education. The boys in his mother's family went to Yale, the girls to Smith. Vamedoe attended debutante balls. He has shot a quail. A person with that background knows about settled authority; Vamedoe will not be a radical or barnburner. MOMA knows that Vamedoe will respect its permanent collection, which is the heart of the place.

Yet he is often impatient with the Savannahs of the world. "There's a sense in a town like that that no matter what you do you're always your father's son or your mother's son, and that's confining in a lot of ways." In the teaching of modem art at Williams College, Vamedoe found a model of excitement, a tradition of "being surprised," that continues to have for him the quality of a revelation. It was not the scholarship or the weight of tradition that initially attracted him; it was the heating up of the moment, the talking and looking and thinking, as he engaged a work of art. In a way, that is still his drug of choice. "I could have the flu and a temperature of 103 and two hours later, after giving a lecture, I'd feel like a hundred bucks."

Vamedoe's students remember him pacing back and forth, losing track of time, talking a mile a minute—and suddenly looking up, aware that the world was staring at him. Vamedoe has always lectured best without notes, as he searches for the right response, idea, phrase. "I remember once he was lecturing on Manet's Olympia," says Patricia Berman, now an assistant professor of art at Wellesley, "and he began to get really worked up about how Manet, who was a dandy and very interested in fine gradations of tone, uses the color black. Kirk has this rhetorical device—restating something over and over again, transforming it along the way—and I remember that he finally ended up by describing the color as 'smoking-jacket black.' We all walked out of the lecture blinking, sort of transported, and looked at each other and said smoking-jacket black."

According to his brother Sam, a photographer, Vamedoe watched an impressive amount of TV as a child. "Obviously it didn't min an extraordinary mind. Maybe he is like those whales who, if they eat enough stuff of low value, get enough nourishment." For Vamedoe it has obviously been second nature to keep one finger on the popular pulse, while coming to admire smoking-jacket black. He is under fifty, an early baby-boomer, and pop to Americans under fifty is usually a given, not an acquired, language. He likes old rock 'n' roll; he still rides a motorcycle.

But it was contact sports that, together with art, seems to have affected him most. Not many people in the art world know what a nose tackle is. Vamedoe actually was one.

"I was a really overweight kid," he says, "and that doesn't make for a very happy childhood. I wasn't a great social success, and you feel it at that age. Then when I went away to boarding school, when I was about thirteen, they kicked my butt very hard. I was put into athletics in a way I hadn't before. I latched onto football as a way of improving myself."

Vamedoe continued to play football at Williams, although he was not a gifted athlete. "As the old saying goes, I may be small but I'm slow," he says. Because he wasn't good enough for the flashy roles, he played the big-guy positions (like tackle), despite his small size. After college, Vamedoe took up Rugby, playing on amateur clubs such as "Old Blue," which is associated with Columbia University. The gentlemanly quality of the rough stuff appealed to Vamedoe, according to a friend and teammate, Jeff Jones. ''It's a self-policing sport in a lot of ways. You compete, but you don't play dirty. I think Kirk is that way."

Jones says Vamedoe enjoyed the freeflowing character of the sport; it was quicker, more improvisational than football, without the regimentation. Vamedoe named his recent book of essays on the nature of modem art A Fine Disregard—the title recalling a famous phrase that describes the invention of Rugby, when, with "a fine disregard for the rules," a schoolboy suddenly picked up the ball and transformed English football into a vital new game.

Almost everyone who knows Vamedoe mentions his intense focus, his devotion to reaching goals. In college, once he had decided to become an art historian, he did so with relentless concentration. Interested in Rodin, he received his doctorate from Stanford, where the Rodin scholar Albert Elsen taught. Vamedoe played the part of apprentice to Elsen, quickly completed his dissertation, and subsequently led a charmed professional life, rich in fellowships, good jobs, and exhibitions. Among other publications, he wrote an important book on the neglected Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte. Eventually he became a tenured professor at the Institute of Fine Arts in New York.

The same intensity that brought him so much success also dismayed many people, including some, like Linda Shearer, formerly at MOMA and now director of the Williams College Museum of Art, who are his friends today. ''I was a curatorial assistant at the Guggenheim in the mid1970s," she says, ''and the museum took a show called 'Rodin Drawings: True and False.' Kirk was working on it. I think he's a year older than I am, and I just found him really offputting. I thought, Who's this guy my age acting like he's telling me what to do and he knows so much more than I do? And I wasn't the only one. It was an attitude of superiority that came across."

When MOMA'S department of painting and sculpture learned that Rubin wanted Vamedoe to succeed him, the curatorial staff objected to the imperial manner of succession. Vamedoe was known principally as an outsider brought in by Rubin to work on the famous "Primitivism" and Vienna exhibitions. "There wasn't any kind of staff uprising, but what happened to poor Kirk is that when you're under scrutiny like that every little thing comes out," Shearer says. "You know, on the level of 'I remember once he was really rude to me in the hall.' Actually it was the best thing that could have happened. Kirk heard things about himself that really made him try to come to terms with what in fact taking this job meant."

The Modern remains a remarkably idealistic institution, if not always a gentle place. Bright people earning peanuts work there because they hope it matters; a certain irritability, typical of those haunted by great expectations and too little space, colors their mood.

Despite the high standards, or perhaps because of them, the museum is famous for its fierce and sometimes petty internal politics. It is not enough to succeed, a wit once said. Others must fail.

Vamedoe's friends think two things could get him in trouble. He can be naive, "curiously without guile." One close friend says Vamedoe is too quick to tell the world his plans, and he has made mistakes people more politically adept might have avoided. For example, on the same day that the "Arts & Leisure" section of the Sunday New York Times published a huge spread on him, the newspaper's magazine ran an ad for Barneys, the New York men's clothing store, which featured Vamedoe identified simply as "Art Historian." He looked like a moody poseur from downtown. The timing was a coincidence, Vamedoe received no money for the ad (instead, the store made a donation to the Coalition for the Homeless), and he says he posed because the photographer Annie Leibovitz asked him to. But the affair was still tacky and gave Vamedoe's detractors the opportunity to whisper about trendiness and stardust.

He can also come on too strong. "Kirk grew up broadcasting himself, because that's what his family was like," says a friend. "He's used to a quick pace. It's not arrogance, but enthusiasm. He wants to finish what you're saying. He's having to learn about what offends people." He has inherited a department that, according to one insider, is often disgruntled and cynical. "To a certain degree Kirk's style has exacerbated this problem in the short term, because he has a very close relationship with a lot of people outside the museum, especially graduate students. He brings them in, which only highlights the noninvolvement of the large and embittered staff."

'He's used to a quick pace; he wants to finish what you're saying. He's having to learn about what offends people."

The art world has watched Vamedoe's search for a successor to Linda Shearer, who was a curator specializing in contemporary art, with a particularly wary eye. A recent rumor that he was considering Jeffrey Dietch, a dealer and consultant, aroused talk that Vamedoe would identify the museum too closely with the commercial art world. In the end, however, Vamedoe did nothing of the kind. He hired Robert Storr, forty, a former painter and now a critic. Vamedoe calls Storr "a pluralist, but not an ideological or textbook person." Vamedoe believes the new curator has the right combination of talents, calling him open to the diversity of today's art world and discriminating about its achievements.

The choice is important in part because Vamedoe works best in a collegial or team atmosphere among people he knows well. "He always wants everybody, including himself, to be giving 100 percent,'' one former student says, "and has no patience with you if you don't." In that context, he attracts genuine loyalty. For example, "High and Low" evolved out of conversations over the years between Vamedoe and Adam Gopnik, who first used the term "High and Low" in a paper he wrote about the influence of Picasso's caricatures on his portraits. "Kirk could have just asked me to write an essay in the catalogue," Gopnik says. "Instead, he asked me to collaborate. Not many people would have done that."

Vamedoe likes artists, not just art. As a child he often drew, and in his lectures he leads students to identify with the process of creating—"of Rodin digging into clay or creating seismographic lines with his pencil," as Patricia Berman put it. In the end, he went all the way and actually married an artist, Elyn Zimmerman.

They met in 1975, after he mentioned one of her works in an article. "I thought he must be old and German," she says, "because that's what most arthistory professors I knew were. Anyway, we met at a delicatessen and I said, 'How will I recognize you?' and he said, 'I'll carry a copy of an art magazine.' So I walked up to the delicatessen and there's Kirk dangling a copy of Artforum in front of his face.... He was funny."

They are remarkably different. Zimmerman makes contemplative environments, usually in cities, that serve as a counterpoint to the frenetic urban style. She is soft-spoken, he is loquacious. She does not come from a social background ("I didn't own a cocktail dress when I came to New York"), he wore tuxedos from an early age. "I told him I'd go to his Rugby matches," she says, "if he'd come to my yoga class."

They seem to enjoy their differences—and they sometimes disagree about art. "Even if we don't persuade each other," he says, "in the long run we learn something about the alternative takes you can have." It was Zimmerman who introduced Vamedoe to many living artists. Knowing them piqued his interest and has made him increasingly sympathetic to contemporary work. "Artists realize how important things come out of everyday activities," he says. "The way Elyn pays attention to things, what she notices, what she refuses to take for granted, is a constant education."

The introduction to "High and Low" begins with an imaginary artist at the turn of the century returning from the Louvre to his studio. He is surrounded by the new visual elements of his day, such as "brightly colored commercial posters,'' "newspapers and cartoon journals," "mean scrawlings on the walls of the darkened side streets." He "dreams of an art that will revive [the old masters'] ideals and rival their grasp of human experience," while finding "languages of form appropriate to the world of machines, science, and social revolution that is emerging all around him."

At the museum, Vamedoe has begun a series called "Artist's Choice," in which a living artist is invited to put together a show of works drawn from the permanent collection. Implicit in the series is the notion that a great tradition comes to life when an artist responds to it in his own idiosyncratic way.

Despite his error with Barneys, Vamedoe could become socially prominent and a broker in the New York power game. The job makes it possible, and the social side of the world "is something like breathing to him," his wife says. "He grew up with it. He knows how to give toasts. I remember at our wedding all his friends from prep school and college got up and gave these fancy toasts. Then all my friends got up—these poor tongue-tied artists."

But Vamedoe has displayed little interest in the social swirl. Those who follow such things say he's not trying. He enjoys company and talking to collectors, but that's about it. "We'll have an invitation to conduct some social studies," his wife says, "and he'll ask, 'Are you interested?' But he's happiest wearing cutoffs on his motorcycle."

Eventually, it may become a more important part of the job. To be successful over the next decade, MOMA will require money and patronage. There must be Leo Castellis who donate art. Others will have to support exhibitions, which are growing more and more expensive as the cost of insuring paintings increases. Many now say MOMA, which once had the field to itself, has grown sluggish with success: countless other museums are competing for the same dollars, pictures, and trustees.

This is partly LAZINESS-MOMA has never really had to hustle—and partly good taste. The Modem is a rather choosy beggar. It has invited fewer of the socially ambitious rich onto its board of trustees than most other institutions. It will not rent itself out for parties that have no connection to the museum, it will not accept a great collection that a vainglorious donor wants named after himself, and it will not hawk catalogues and doodads at the entrance and exit to an exhibition. (Many at MOMA feel guilty about the occasional use of Acoustiguides.)

The funny money flying around the auction houses has made gentlemanly gifts like Castelli's increasingly hard to come by. Unless Congress changes the tax law to make works of art fully deductible, as they were until recently, museums are going to receive fewer and fewer gifts. "When you're sitting on the sofa and you look across the living room at your Matisse and you say, 'That's the Porsche I didn't buy,' well, O.K.," says Vamedoe. "But when you look across the living room and see the apartment on Fifth Avenue, the grandchildren's education, the trip to Saint-Tropez, and security for the next four generations, then I'm sympathetic."

At the same time, with pictures now being traded as commodities, fewer will be settling into other museums. That gives the Modem a chance to improve its collection in areas where it remains weak. Soon the museum will need to expand yet again, to push the permanent collection into the 1960s, '70s, and '80s; finding the necessary space in midtown Manhattan will be nightmarish. The museum may rent a space apart from the main building as an interim solution, but for the long term Vamedoe is determined to keep the entire collection together, in order to maintain the stately beauty of an ongoing story richly told.

MOMA'S many qualms help sustain morale, because no decent curator wants to think he's in public relations, whether for a corporation or an individual. But such qualms are also expensive. For most of its history, the Modem has been insulated from temptation by serious money, especially Rockefeller money. The connection between that family and the museum is a good example of the partnership that, in the earlier years of modernism, would sometimes form between old money and new taste. Old money was secure enough, and proud enough, to join in the challenge that modem art flung at middlebrow conventions. But the Rockefeller family will play a reduced role in the future. There remain young Rockefellers interested in the museum (David junior is an active trustee with a special interest in education), but, as David senior says, "with the spreading out of our family and the division of our resources to a much larger number of people, it would be unrealistic for the museum to expect the family to play as dominant a role as it has in the financial support of the museum."

Curators occasionally take important people through a MOMA show. It once fell to Vamedoe to guide Mayor Ed Koch, who is not known for his knowledge of art, through the museum's Vienna exhibition. Vamedoe has an instinctive feel for the audience at hand and (like many postmodernists) enjoys the quick zip of the unexpected connection. While strolling along, this particular odd couple came upon one of Egon Schiele's pictures of an angst-contorted adolescent. The populist mayor did not have much to say. Vamedoe quipped, "This is what Mick Jagger wishes he looked like."

Many pious people in the art world would not find that funny. But that (funny) remark is characteristic of an outlook that has played a critical part in the evolution of modernism. The comment is irreverent—but in the service of an important freedom. Good artists often treat the past as conversation rather than writ. They themselves usually fail to make anything that lasts much longer than a quip, but the effort to bring the settled past into the transitional present keeps an artist fresh. The same can be said of curators. Vamedoe's quip acknowledges Schiele's primacy while recognizing that Mick Jagger is working on related material. "High and Low" will have that kind of spiky, ambivalent modem personality.

Vamedoe is part of a younger generation of art historians who have emphasized the cultural context of art-making; his first passion is the blooming of ideas in and around a work of art. But he is not an ideologue. He worries about various art-world tyrannies, "on the one side the international culture machine, on the other agitprop." Over the years, he has also become increasingly sensitive to purely visual values. It is not yet clear if he has a good eye for art, but he recognizes that a great work is more than the sum of its ideas or issues. "I started with the notion that if the high-low theme didn't involve elucidating something important about what I regard as truly significant major art of the twentieth century, then it wasn't a theme worth pursuing, ' he says. "So it starts from a premise of hierarchy; it is just that those hierarchies are not dependent upon the fixed rules of the nineteenth century or upon certain academic pigeonholes."

He hopes to maintain the canonical aura of the permanent collection while also diminishing its air of carrying out a forced academic march. He is framing pictures in a variety of ways, arguing that some were "screaming in pain" in the uniform MOMA frame, and he wants visitors to be able to move in and out of the galleries more easily, more serendipitously, without having always to acknowledge that this came before that.

As the year 2000 approaches, Vamedoe plans three shows that will "attempt to give intellectual shape to the postwar era." His essential brief is to collect and examine the art after the generally admired and well-represented Abstract Expressionists, from about 1955 to 2000. He has been invited to give the Slade lectures at Oxford, in which he will focus on this later period. "What happens to the modernist juggernaut after the war and up to the last decade, the issues that this art raises—that's what I want to explore."

As a curator, Vamedoe will probably err on the side of including rather than excluding. He may want to regard as important certain work that is just the last gasp of a great tradition; the section in "High and Low" on contemporary art, for example, will likely be the weakest (too much Mick, not enough Egon). But MOMA should maintain a passion for the contemporary as long as possible. It should aim to give the present its best shot, in the light of the past. History will eventually take care of what counts.

Vamedoe's brother Sam worries that the press of business at MOMA may prevent Vamedoe from "deeper research, from developing the conceptual side of what he does." Yet the lively tension between being a free-flowing breaker of rules and the custodian of a great collection could also prove fruitful. Many people continue to treat MOMA as a secular temple, hating it and loving it, depending in part on how they feel about temples. Vamedoe is an interesting, unsettling choice for the biggest job there, because he does not easily fit into any particular camp. He likes being an intellectual pilgrim. He asks questions to which he doesn't know all the answers. He resembles the seductive young preacher who comes to a somewhat sleepy and orthodox church, stimulating the young and making the graybeards nervous.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now