Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

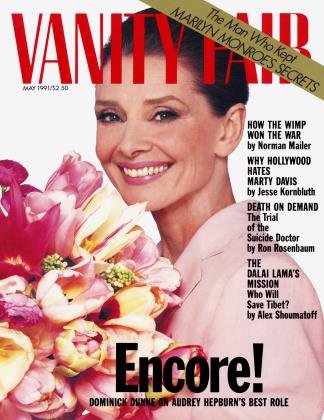

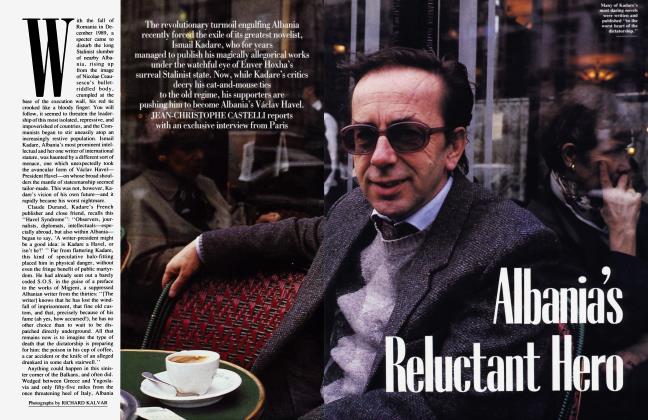

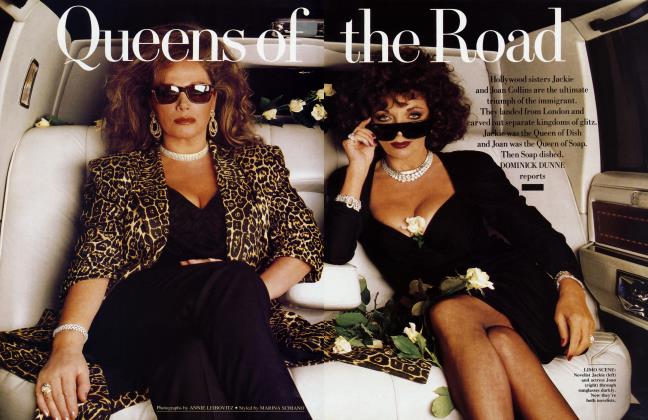

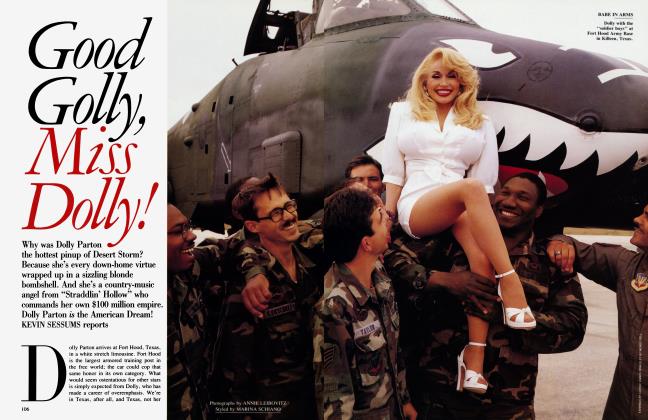

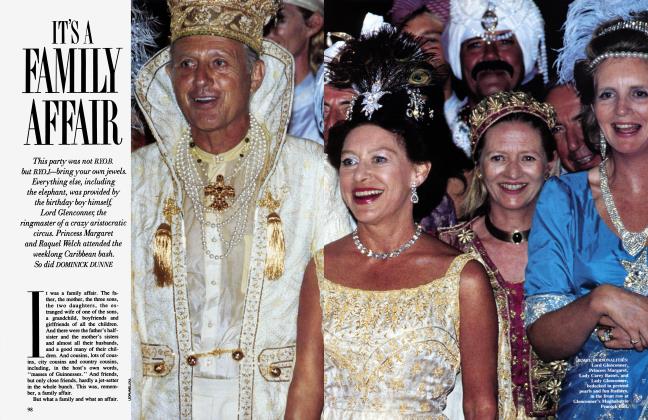

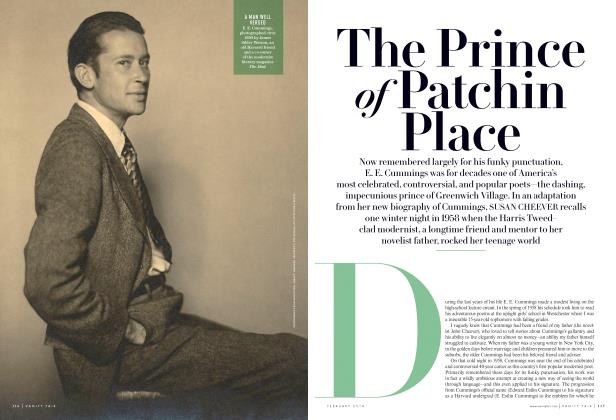

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe war-devastated children of the Persian Gulf have their most dynamically eloquent champion in Audrey Hepburn, who has exorcised haunting memories of her own wartime childhood with the most demanding role of her career, as an ambassador for UNICEF. DOMINICK DUNNE reports why Hollywood's most stylish gamine shunned the superficialities of show biz and found the cause that redefined her life

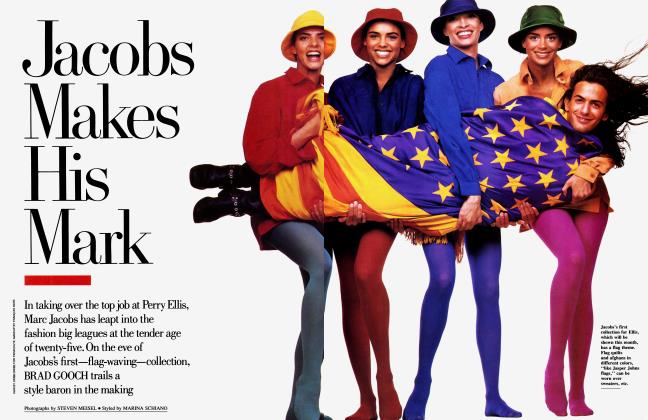

May 1991 Dominick Dunne Steven Meisel Marina SchianoThe war-devastated children of the Persian Gulf have their most dynamically eloquent champion in Audrey Hepburn, who has exorcised haunting memories of her own wartime childhood with the most demanding role of her career, as an ambassador for UNICEF. DOMINICK DUNNE reports why Hollywood's most stylish gamine shunned the superficialities of show biz and found the cause that redefined her life

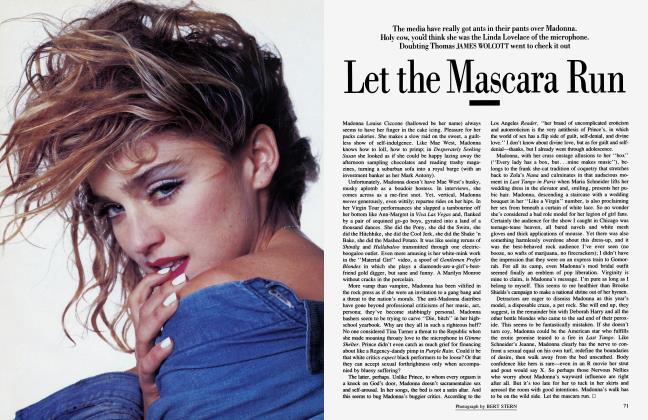

May 1991 Dominick Dunne Steven Meisel Marina SchianoLet's start with a given. The lady, as the lyric goes, simply reeks of class. In Roman Holiday, her first starring role, Audrey Hepburn burst onto the screen as the princess of an unnamed country, and, through the nearly four decades since, she has never quite lost the royal mystique she played so convincingly that she won Academy Award for it. People stare at her differently from the way stare at other movie stars. They are more respectful. Several princesses of the blood on the world scene today could take lessons from her in convivial deportment. She long ago removed herself from the world that made her famous, but she has retained her ability to remain a star. In this early twilight period of her life, when she is receiving homage for past achievements and for her new role as goodwill ambassador for UNICEF, she is curiously available, exuding a radiance that no other star even approaches. "I've never spoken in public, in my life, until UNICEF," she says. ''It scares the wits out of me." But you would never know it. Watch her glide across a ballroom floor with ballerina-like strides, dressed by Givenchy, acknowledging a standing ovation. The word "elegant" was invented for her. Watch her listen shyly to words of praise being heaped on her by toastmasters, former co-stars, and directors. And then listen to her speak in the lilting voice we know so well, in the not quite definable accent of a person proficient in several languages, casting the same spell in her new role as ambassador that she cast so consistently in her twenty-six films.

At a benefit in Dallas recently for the U.S.A. Film Festival and the United States Committee for UNICEF, Audrey Hepburn was honored for having made enduring contributions to American motion pictures. This month, the Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York will hold a gala in her honor. After the Dallas benefit, she said about the praise, "It's all so—how shall I say it?—it's wonderful, but at the same time you don't know where to put yourself. You just die in a way. I mean, all those compliments. You wish you could spread it over the year. It's like eating too much chocolate cake all at once. And you sort of don't believe any of it, and yet you're terribly grateful."

She has the same reticence about the public praise she receives for her UNICEF work. "It makes me self-conscious," she said. "It's because I'm known, in the limelight, that I'm getting all the gravy, but if you knew, if you saw some of the people who make it possible for UNICEF to help these children to survive. These are the people who do the jobs—the unknowns, whose names you will never know. They give so much of their time. I at least get a dollar a year, but they don't, UNICEF went into Baghdad on February 16, before the cease-fire. There was a convoy of trucks with fifty tons of medical supplies for the children and mothers. They also went there to ascertain the future needs of Iraq and Kuwait. There is no electricity, no water, no sanitation, no heating. The water-purification plants are closed down. The sewage system is backed up. People are both bathing in and drinking from the Tigris River. . ."

It's only fair to say that I did not come to Audrey Hepburn for this interview as a total stranger. I have had a longtime acquaintance with her, as a friend of several of her best friends, and have some vivid memories of her from times past. One Sunday afternoon in Beverly Hills in the early sixties, I watched her alight from a limousine with Mel Ferrer, her husband at the time, and the then married Elizabeth Taylor and Eddie Fisher and run into the Canon Theater for the matinee, as if they were all ordinary people. Another time, at a party at Gary and Rocky Cooper's house in Holmby Hills, I watched her laugh with baritone abandon at a funny story of Billy Wilder's, who had directed her and Gary Cooper in Love in the Afternoon. In Rome, during the time of her second marriage, to Dr. Andrea Dotti, at a large and boisterous spaghetti dinner at the home of her then mother-in-law, I watched her sit in dutiful daughter-in-law docility, drawing no attention to herself, while her husband's mother reigned as the undisputed star of the evening. And more recently, at one of Irving and Mary Lazar's famous Academy Award parties, after she and Elizabeth Taylor had warmly embraced, I saw her point to one of Elizabeth's enormous jewels and ask, "Kenny Lane?," to which Elizabeth Taylor replied, "No. Richard Burton." And the two stars screamed with laughter.

When I reminded Audrey of the time she and Elizabeth Taylor and their husbands of the period had raced into the Sunday matinee in Beverly Hills, her reaction was typical. "That was their limousine," she said about the Eddie Fishers. "We didn't have one." As for laughing at Billy Wilder's story, she said, "I love people who make me laugh. I honestly think it's the thing I like most, to laugh. It cures a multitude of ills. It's probably the most important thing in a person. David was so funny—David Niven. And Billy, of course. I mean, I don't have the talent to make people laugh." When I asked Billy Wilder for his impression of her, he said, "Ah, that unique lady. She's what the Latin calls sui generis. She's the original, and there are no more examples, and there never will be."

Cecil Beaton once described the young Hepburn as "looking like a Modigliani on which the paint has hardly dried." With the passing years, her beauty has matured but not diminished, and, God knows, she didn't get fat, or lifted. There were moments during the time I spent with Audrey Hepburn when the public and press excitement was so great I felt as if I were with Madonna rather than with a sixty-two-year-old woman, semi-retired from the screen, who now works tirelessly for a cause that Gregory Peck, her first co-star, calls "her most wonderful and rewarding role, which she plays around the world."

"Does it surprise you, the incredible excitement that you still cause?" I asked her.

"Oh, totally," she said. "Everything surprises me. I'm surprised that people recognize me on the street. I say to myself, Well, I must still look like myself. I never considered myself as having much talent, or looks, or anything else. I fell into this career. I was unknown, insecure, inexperienced, and skinny. I worked very hard—that I'll take credit for—but I don't understand any of it. At the same time, it warms me. I'm terribly touched by it."

With the passing years, her beauty has matured but not diminished, and, God knows, she didn't get fat, or lifted.

In public situations, there are those who are content merely to stare at her, but there are more, especially women, who feel the need to confide in her. Often she gives her full attention to the stranger's confidence. Two days after one such encounter, she said to me, "That girl who was kneeling there is the mother of two daughters, I think she said, and she and her husband are leaving next week for Romania because they have adopted two Romanian children, one newborn and one three years old." In New York, an autograph hound accosted her on the street with a glossy photograph from Breakfast at Tiffany's. She signed the picture for him, and then he pulled out another one, and then another, and another. In the car, she said, laughing, "There used to be a time when you'd just sign the autograph. Now they bring along fifteen pictures for you to sign." The day she was signing copies of her book, Gardens of the World, in Ralph Lauren's flagship store at Seventy-second Street and Madison Avenue, the crowds were so great that the line extended from Madison all the way to Park Avenue, and many of the people waiting patiently in the cold were not able to get in. "I had to leave out the back because of the crowds," she said. "I feel bad because all those people were left standing there in line for so long."

Audrey Hepburn was born in Belgium, the only child of a Dutch baroness and an English-Irish banker named Hepburn-Ruston. She had two older Dutch half-brothers from her mother's first marriage. "I lived and was based in Belgium until I moved to Holland, so my first words were French, but I spent a lot of time in England. My mother couldn't afford an English nanny, and she wanted me to speak English, so she would send me every summer to stay with a family I absolutely adored."

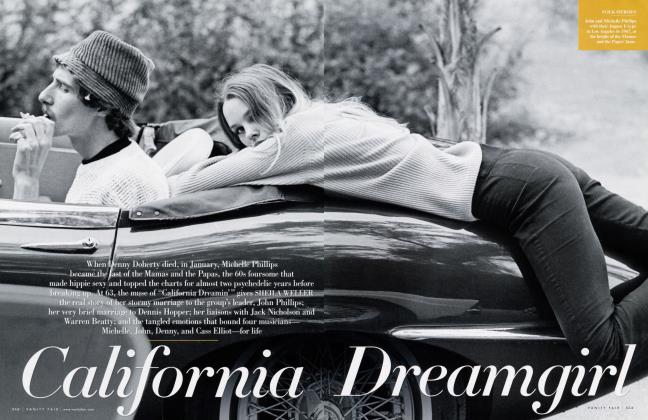

When she was six years old, a family event occurred that was as emotionally devastating for her as the war that would soon follow. Her father, for reasons she did not speak about, left her mother and vanished out of her life. "My mother went through sheer agony when my father left. Because he really left. I think he just went out and never came back. I was destroyed at the time. I cried for days and days. But my mother never, ever put him down."

In the years between childhood and her international stardom, she saw him only once, in 1939, when she was ten. She was in England for her annual summer stay, and the Second World War began. "My mother, who was in Holland with the boys, was anxious to get me out of England and back to Holland, because Holland was neutral. There were still a few Dutch planes that were allowed to fly. Somehow my mother had contacted my father and asked him to meet me at the train in London from where I was coming in. They put me on this bright-orange plane. You know, orange is the national color, and it flew very low. It really was one of the last planes out. That was the last time I saw my father."

"And you never saw him again?"

"I located him after the war. I had to know if he was still alive, and through the Red Cross I found him. He was living in Ireland. And that was that."

"But you didn't see him?"

"No. Because I had been cut off from him, and he had never tried to reach me, nor did he ever want to see me." The memory of her rejection by her father was painful for her, and personal revelations are rarely forthcoming. "I think it is hard sometimes for children who are dumped. I don't care who they are. It tortures a child beyond measure. They don't know what the problem was. Children need two parents for their equilibrium in life. I mean emotional equilibrium. That's why I was so terribly anxious for my own two boys to stay close to their fathers, in spite of my divorces."

Years later, she said, "I had a letter from my mother saying that she had heard my father had died. I was married to Mel Ferrer then. I was so distraught. I realized how much I cared. I'd always cared, obviously. When he disappeared, I always wished I'd had a father. Other kids had one, and I didn't. I just couldn't bear the idea that I wouldn't see him again. Mel said, 'Maybe it's not true. Did it ever occur to you that he's still alive?' He went about finding him, and discovered that he was still living in Dublin, and we went to see him."

"Was he aware of your fame and success?"

"Yes, but in a very. . ." She paused and let the sentence dangle. "I think he was proud. My mother was that way, too. My whole family was. It was a job well done, but you didn't make a lot of fuss about it."

On several occasions, she described her mother as a lady of very strict Victorian standards. "I could always hear my mother's voice saying, 'Be on time,' and 'Remember to think of others first,' and 'Don't talk a lot about yourself. You are not interesting. It's the others that matter.' "

"Is your mother still alive?"

"She died in '84. At my home. In Switzerland. She lived there for the last ten years of her life."

"You were very close to her, weren't you?"

She looked straight ahead. "I was very lucky to be able to take care of her, because I always think it's so sad when people have to die away from home. She was bedridden for three years."

On the night before the Germans invaded Holland, eleven-year-old Audrey was taken to the ballet by her mother to see the Sadler's Wells Ballet company perform. "I had this tremendous love of ballet. For the occasion, my mother had our little dressmaker make me a long taffeta dress. I remember it so well. I'd never had a long dress in my life, obviously. There was a little round collar, a little bow here, and a little button in the front. All the way to the ground, and it rustled, you know. The reason she got me this, at great expense—we couldn't afford this kind of thing—was that I was to present a bouquet of flowers at the end of the performance to Ninette de Valois, the director of the company. All during the performance there were rumblings going on, and the dancers were all ready to leave right after. I remember walking onto the bright stage, with the pretty ballerinas and their costumes. They had been ordered back to England. And the next morning, after my first late night, the Germans came to Holland. We were told not to open the curtains and not to look out of the windows, that we might be shot at. They came to our town with armored cars and tanks, with machine guns trained on the roofs."

"Ah, that unique lady," said Billy Wilder. "She's the original, and there are no more examples, and there never will be."

Her brother Ian, who was a member of the Dutch Resistance, was captured by the Germans, and for years the family did not know whether he was dead or alive. He was taken to Germany as a forced laborer. Her other brother was in the Dutch army, which was easily defeated by the Germans, and he went into hiding for the remainder of the war. At the time, the half-English Audrey couldn't speak a word of Dutch, and her mother was terrified that she might be put into a camp. In order to make her appear as Dutch as possible, she was enrolled in a Dutch school under her mother's maiden name, van Heemstra, rather than Hepburn. ''During the last winter of the war, we had no food whatsoever," she said. In 1945, after five years of war and occupation, she was malnourished and suffering from a variety of diseases. "I finished the war highly anemic, and asthmatic, and all the things that come with malnutrition. I had a bad case of edema, which also comes with malnutrition. It's a swelling of the limbs. It's all lack of vitamins."

With the arrival of the Allies, she became one of the first recipients of benefits from UNRRA, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, the forerunner of UNICEF, which was created the following year. ''You know, five years of malnutrition is no joke," she said. Her emotional commitment to the organization began then, although her active participation did not begin until four years ago. ''I auditioned for this job for forty-five years, and I finally got it," she said in a recent speech to UNICEF volunteer workers in New York.

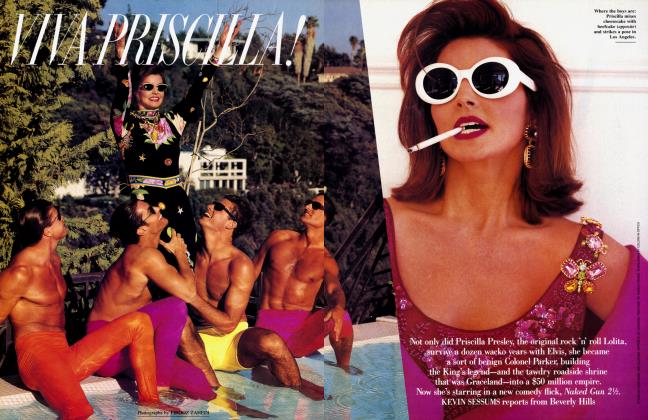

The almost instant and spectacular success of Audrey Hepburn the film star seemed predestined. After the war, she went to England as a dancer. "I worked like an idiot," she says. "It was work, work, work, work. I did two shows at the same time, a musical revue at the Cambridge Theatre, twelve performances a week, and then we were all shipped to Ciro's nightclub right after the show, and there we did a floor show. And I was doing television. I did anything to earn a buck so that my mother could come over and join me." She also did bit parts in six films, including The Lavender Hill Mob. But it was while she was doing an unmemorable scene in an unmemorable film called Monte Carlo Baby that the circumstances of her life were changed forever. "It was the Hotel de Paris in Monte Carlo. I had one scene—going up to the hall porter and asking for my key. Colette used to go there with her husband to convalesce every winter. I knew about Colette—that she was a writer, a French writer—but I don't think I was aware then what a great writer she was. She was very ill with arthritis or rheumatism and was in a wheelchair. I was standing in the lobby, and Colette said to her husband, 'Maybe that is the girl that's right.' I was asked to meet her, and I was thrilled. She asked me if I would like to do a play—to do Gigi— on Broadway. When I went back to London, I was contacted by Gilbert Miller, who was producing the play. Then, that same month, Willy Wyler came to London from Hollywood. He was looking for an unknown girl who had the makings of a star to play the part of a princess in Roman Holiday."

It is impossible to recollect a more auspicious beginning. She got both parts. To accommodate the unknown, the shooting of Roman Holiday was sandwiched between the Broadway run and the road tour of Gigi. In the same year, she won both an Oscar for Roman Holiday and a Tony for her next play, Ondine, in which she starred with Mel Ferrer. In the fifties and sixties, she appeared in such memorable films as Sabrina, War and Peace, Funny Face, Love in the Afternoon, The Nun's Story, The Unforgiven, Breakfast at Tiffany's, Charade, My Fair Lady, Two for the Road, and Wait Until Dark, playing opposite most of the legends of the screen, all older than she—Humphrey Bogart, Gregory Peck, Gary Cooper, Cary Grant, Burt Lancaster, William Holden, Rex Harrison, Henry Fonda, and Fred Astaire. In interviews, she hates being asked, as she frequently is, who her favorite leading man was. "Could you decide between . . .?" she asks, and then she reels off the list of great names, adding, "I loved them all."

The film critic Molly Haskell recently wrote of her, "By the mere raising of an eyebrow, or the injection of irony or pathos into a line of dialogue, she can disinfect an unsavory situation, can turn the forbidden into the desirable." Throughout her career, even on the single occasion she played a lady of easy virtue, she retained her untarnished image, never descending to the tawdry. Truman Capote made no secret of his distress when she was cast as Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany's. He had wanted Marilyn Monroe to play the part. "Marilyn would have been absolutely marvelous," he said. "Audrey is an old friend and one of my favorite people, but she was just wrong for that part." Yet, thirty years later, it is that role, along with the princess in Roman Holiday, that she is most identified with in the public mind.

After Wait Until Dark, with the expert timing of a great star, she withdrew from her career, of her own accord, to be a mother to her sons, Sean Ferrer and Luca Dotti. She was never a Hollywood resident or even a bona fide member of the film community. Like an elusive sprite, she alighted there for each film, lived in rented houses, saw only a small group of friends, and left at the end of each picture for her home in Switzerland, where she has lived since the mid-fifties. During her second marriage, to the Italian psychiatrist Andrea Dotti, she also maintained an apartment in Rome. There have been occasional film appearances, but the days of stardom are over, and when she talks about them, there is no sense of loss. She finds total contentment in her new role with UNICEF, her beautiful Swiss home, and her well-established relationship with Robert Wolders, a former actor eight years her junior, who is the widower of the glamorous film star Merle Oberon, who died in 1979. Audrey and Robbie, as she calls him, have not married. They seem to have no intention of marrying. But they are very much in love, and very, very together.

"It was clear that Robbie and I had found each other at a time in our lives when we were both very unhappy. And we're terribly happy together.'' When they met, at the Beverly Hills home of Audrey's great friend Connie Wald, the widow of the film producer Jerry Wald, Audrey's marriage to Andrea Dotti had ended, and Merle Oberon had died several months earlier. "It was very curious. I never met him with Merle. I knew Merle, adored her. I met her several times during my life. But when I was living in Rome, I didn't go to Hollywood much, and Robbie and I never met."

"What is your life like in Switzerland?"

"Divine," she said, pouncing on the word, elongating it, pronouncing it in capital letters, and shutting her eyes to experience it. "It is everything I long for. All my life, what I wanted to earn money for was to have a house of my own. I dreamed of having a house in the country with a garden and fruit trees. I found it, and I've had this particular house for— what is it?—twenty-six years. I've lived in Switzerland for thirty-six years. I love it. I love the country. I love our little town. The shops. I love going to the market. They have an open market twice a week with all the fruit and vegetables and flowers. And Robbie and I are potty about our dogs."

Until recently, they had four Jack Russell terriers, but their favorite, Tuppy, a gift from Audrey to Rob for his fiftieth birthday, four years ago, died just before their latest trip to America, and their grief for the lost pet is immense. "Robbie had never had a dog of his own, and I thought he should have one," she said. "I think an animal, especially a dog, is possibly the purest experience you can have. No person and few children, unless they're still infants, are as unpremeditated, as undemanding, really. They only ask to survive. They want to eat. They are totally dependent on you, and therefore completely vulnerable. And this complete vulnerability is what enables you to open up your heart completely, which you rarely do to a human being. Except, perhaps, children. Who thinks you're as fantastic as your dog?"

With the expert timing of a great star, she withdrew from her career, of her own accord, to be a mother.

When the handsome, bearded Wolders walks into the room, the affection and rapport between the two of them is immediately apparent. "I could never have done all of this work with UNICEF without Robbie. There's no way. Apart from my personal feelings, there's just no way the job could have been done. He's on the phone the whole bloody time. He's the one who gets all the flights, for free, UNICEF can't pay for hotels and other things. He's marvelous at it. Sometimes he cajoles airlines for UNICEF needs. He does a million things. When we get to a town where I have to speak the next day, he'll go and check the room and the mike, and he'll listen to what I'm going to say, and he'll tell me, 'No, that isn't right,' or 'It's O.K.,' or whatever. And we have each other to talk to."

"How much of your time is devoted to UNICEF?"

"Well, since we started, it's really been full-time. When I say full-time, I don't mean full-time on the road fundraising, or in the field. You're home for three weeks, or even two months, but it's always there. When they asked me to help, I was only too happy to accept, but I didn't know what I was getting into. The whole thing terrified me, and still does. I wasn't cut out for this job. It doesn't mean that because I was an actress I got over being an introvert. Acting is something quite different from getting up in front of people over and over again in so many countries. Speaking is something that is terribly important. And having to be responsible. You can't just get up and say, 'Oh, I'm happy to be here, and I love children.' No, it's not enough. It's not enough to know that there's been a flood in Bangladesh and seven thousand people lost their lives. Why the flood? What is their history? Why are they one of the poorest countries today? How are they going to survive? Are they getting enough help? What are the statistics? What are their problems?"

"Would you be very shocked if I poured myself a small whiskey?" asked Audrey Hepburn one afternoon. ''It's awfully early, I know, but it must be six o'clock some where in the world." She sprang up from the sofa and did just that. Lest we think of her as a Givenchy-clad Mother Teresa or, as someone has suggested, Saint Audrey, it should be pointed out that there is the occasional unexpected element to mar the perfection. In a long-ago interview, Shirley MacLaine, who starred with her in The Children's Hour, said about her, ''She taught me how to dress, and I taught her how to swear." It's minor swearing, to be sure—a "damn" here, a "hell" there—but coming from Audrey Hepburn it does have a surprise quality. "I worked my ass off," she said at one point, describing the years before fame. "I was just a skinny broad," she said another time.

For a lady of fashion, she travels light. Two suitcases and a carry-on. On a recent six-city tour in the United States to raise money for UNICEF, she dressed mostly in black, and, unstarlike, she repeated evening dresses. The jewelry was light too, a good string of pearls and some diamond earrings, but she was still the best-dressed lady in every ballroom. In hotels, she presses her own clothes, does her own hair and makeup, and answers her telephone without disguising her voice or pretending she's her maid. She makes no late star entrances. In fact, often she's where she's supposed to be before the key people arrive. One day, speeding down Second Avenue in a gray Bentley on the way to UNICEF House, where she was to address three hundred volunteer workers, she realized she had forgotten her lipstick and knew there would be photographers there. Rob Wolders suggested that the car return to the hotel. "No, no. That will make us late," she said. "Just pull in at a pharmacy," she called out to the driver. When the car stopped, she dashed out, followed by Rob, ran into the store, got the lipstick, waited in line to pay for it, dashed out, and got to UNICEF House in time to give her speech.

Understand this: she is no figurehead ambassador. "The work that Audrey Hepburn does for UNICEF is imperative for us. It's an absolute necessity," said Lawrence E. Bruce Jr., the president and C.E.O. of the United States Committee for UNICEF. "Many people think that UNICEF gets a slice of the U.N. pie, which is not the case. The organization has to raise its funds each year, so fund-raising is an ongoing effort." Although fund-raising is a major part of Hepburn's involvement with UNICEF, merely appearing at fashionable benefits in no way approximates the extent of her work for the organization, or her passion for her field assignments. During the past four years, she has made field trips to many of the 128 countries UNICEF serves, including Bangladesh, the Sudan, Ethiopia, El Salvador, and Vietnam. The work is hard. The hours are long. The conditions are difficult. On several occasions, namely in Ethiopia and the Sudan, she has been in personal danger when meeting with both the rebel leaders and government leaders. In each country, she learns, understands, and can discuss the problems. "Do you know how many street children there are in South America?" she asked. "All over the world? Even in our country? But especially in South America and India. It's something like a hundred million who live and die in the streets. . . . Contaminated water is the biggest killer of children. They die of dehydration caused by diarrhea, which is caused by them drinking the contaminated water. . . . Last year we provided 52 million schoolbooks for Bangladesh, and in the last eight years we have sunk 250,000 tube wells. They are too poor to have a sanitation system. For a hundred dollars you can pierce a tube well and pump water. It's all done by local labor, but we provide the tubes, the pipes, and everything so that the water can be distributed with the proper sanitation."

The telephone rang, and again she sprang from her seat and answered it herself. "Michael!" she said in a delighted voice when the caller identified himself. It was the composer and symphony conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, calling from Florida. At the end of May she is scheduled to appear in concert with him in London, reading selections from The Diary of Anne Frank to music written and conducted by Thomas at a charity event to raise money for UNICEF. When she returned to her seat, she looked at me. "I'm glad I've got a name, because I'm using it for what it's worth. It's like a bonus that my career has given me, with which I can still do this."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now