Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNight and the City

Not much gave Henry Miller pause. BrassaV managed. In Tropic of Cancer, the (usually highly autobiographical) novelist has the BrassaT-based character asking him to pose for some erotic photographs. Miller obliged, he writes. Of course. BrassaV, who was born Gyula Halasz in 1899 (his nom de camera was taken from his birthplace, Brasso, Transylvania), had come to Paris in 1924 and worked as a journalist. He had come to photography not out of interest in the form—which he would claim he had always disliked—but because he wanted to capture Parisian nightlife. The accomplishments of this familiar avant-garde figure are on display from March 5 through May 1 at the Houk Friedman gallery in Manhattan.

BrassaV's drive to report comes through most strongly in his own words. (Some photographers may have written more— Cecil Beaton comes to mind—but none better.) "The owner looks you over with an unfriendly glance," he wrote of a typical pimp hangout in The Secret Paris of the 30's. "You may not be served, you may even be asked to leave, especially if you try to take pictures. . .And yet, drawn by the beauty of evil, the magic of the lower depths, having taken pictures for my 'voyage to the end of night' from the outside, I wanted to know what went on inside, behind the walls, behind the facades, in the wings: bars, dives, night clubs, one-night hotels, bordellos, opium dens."

BrassaV revered outcasts and bohemians, but he looked at them, as he looked at all his subjects, squarely. He would make very few exposures in shooting a portrait, sometimes only one, rejecting the idea that truth could come from catching his subjects off guard. His photographs of graffiti antedate Dubuffet and Art Brut, and he was perhaps the last photographer who could locate something truly sublime in fog, fireworks, shadows, electric light.

But it is in his pictures of the nightlife of Paris, and its dangerous subcultures, that BrassaV is at his most romantic without debilitating sentimentality. His dignified, unlovely whores and cocky hoodlums are neither glamorized nor condescended to. BrassaV had heart. As for the photographs of Henry Miller in flagrante, no doubt researchers are panting for them, but they seem to have vanished without a trace.

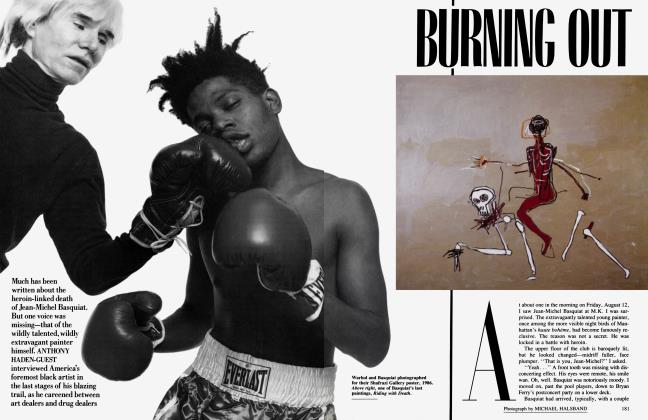

ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now