Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

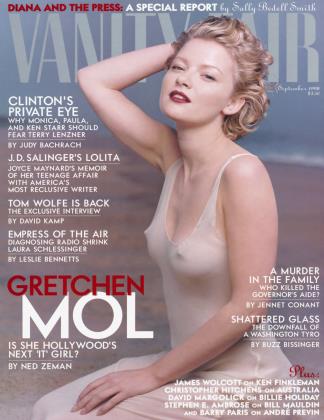

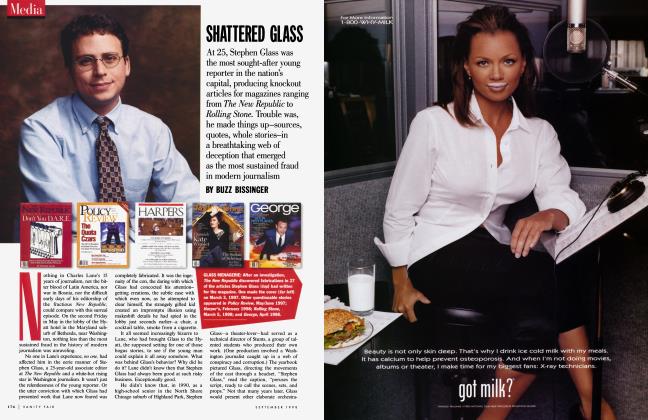

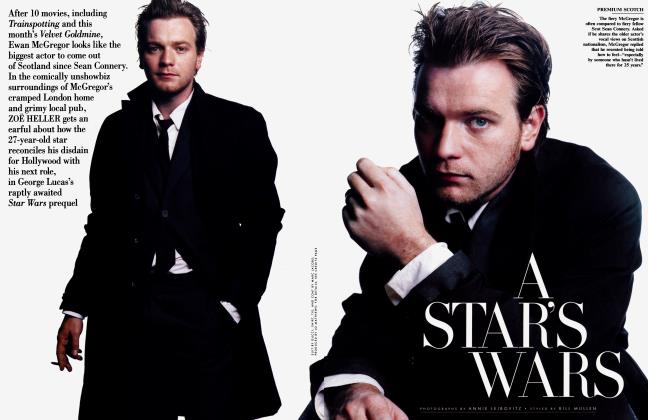

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFor months, Gretchen Mol has been in the celebrity waiting room, a complete unknown with two prominent roles under her belt—with Matt Damon in John Dahl's Rounders and opposite Leonardo DiCaprio in Woody Allen's Celebrity. At Mol's tiny apartment in New York City's Hell's Kitchen, NED ZEMAN meets the recently retired coat-check girl who has the talent to captivate Woody Allen, the humor to deal with a boisterous DiCaprio, and the sense to fear her approaching shot at stardom

September 1998 Ned Zeman Annie Leibovitz Nicoletta SantoroFor months, Gretchen Mol has been in the celebrity waiting room, a complete unknown with two prominent roles under her belt—with Matt Damon in John Dahl's Rounders and opposite Leonardo DiCaprio in Woody Allen's Celebrity. At Mol's tiny apartment in New York City's Hell's Kitchen, NED ZEMAN meets the recently retired coat-check girl who has the talent to captivate Woody Allen, the humor to deal with a boisterous DiCaprio, and the sense to fear her approaching shot at stardom

September 1998 Ned Zeman Annie Leibovitz Nicoletta SantoroAnyone who says Gretchen Mol hasn't suffered for her art wasn't around last March, when she was officially sucked into the bizarre cultural vortex of the Pre-Celebrity. There she was at the Oscar party thrown by this magazine, lovely in her green Armani gown, seated at a plum table alongside Kirk and Michael Douglas, socialite Lynn Wyatt, and director Barbet Schroeder. At some point the guests were discreetly informed that the sweet, deferential, completely unfamiliar woman sitting with them was a promising young actress—Gretchen Mall? Mole? whatever—whom they'd soon be seeing in two big-deal films. Mol smiled, said she was honored, and sat on the edge of her teeth.

Who could blame her? When guests came by to pay homage, they were greeted by Michael Douglas, who pivoted toward Mol and, flashing his toothy rich-guy smile, gushed, "She's sizzling! She's hot! She's on the brink!"

After that, the rest of the evening was a blur.

A few weeks later, at the Washington Hilton, Mol gamely attended the annual White House Correspondents' Dinner, a black-tie affair at which journalists somehow persuade real celebrities to join them for an evening honoring the president. Mol, who managed to appear charmed by the lowliest policy twerps and wire-service factotums, was seated across from a successful young journalist. Unfortunately for her, what followed was the sort of moment that every reporter dreams will happen but never does:

Starlet: Oh, I know who you are. Loved your book.

Journalist: Thanks—and what do you do?

So there it was: the brief but potent hazing of Gretchen Mol, an uncommonly sensible 25-year-old who is poised to go from virtual anonymity—make that complete anonymity—to something approaching full-blown stardom, thanks to her upcoming roles in John Dahl's Rounders, starring Matt Damon and Edward Norton, and Woody Allen's aptly titled Celebrity, starring Leonardo DiCaprio. The sheer velocity of Mol's ascent cannot be overstated. "I hadn't heard of her until she came in and read for the part," says Damon. Mol has appeared in a substantial screen role precisely once, in the mystifying Beatnik indie The Last Time I Committed Suicide.

"She came in at the last minute, and there was a moment of panic. Then she settled down and took the role."

Once is also the number of times she's been recognized in public, ever. "Once," Mol says for emphasis. "I was walking by the RIHGA Royal Hotel at six A.M. There's this guy—Radio Man? Radio Head?—who rides around on a bike to all premieres. He has a red face and long, gray hair, and carries this boom box covered in tape. I don't even think the box works. Anyway, he rides by and says"—leering troll face—"'Gretchen Mol.''"

How out-of-nowhere is Gretchen Mol? For starters, she has few world-weary young-celebrity friends—no Fairuzas, no Skeets—and finds her one scurrilous tabloid mention "funny." Meantime, her publicity pack consists of a mere half-dozen gooey, Tiger Beat-ish blurbs in which Mol is described, without a whiff of shame, as a "pearl-like Prussian dish" with "Jesus H. Christ cheekbones" and "a face like a tournament rose dipped in whipped cream." (Actually, those are all from one article. Appallingly, they happen to be accurate.) "Ooooh," Mol sighs, pawing through the clippings, Frisbee-eyed. She's never seen the whole press pack, and she's all over it. "Whoa! ... Does that look like me? ... That's not my mouth! ... Hmm ... They straightened my nose. "

And then there's the living situation, which is not evocative of pearl-like Prussian-dish-ness. Mol rents a tiny third-story walk-up in Hell's Kitchen, the scrappy Manhattan neighborhood which looks like the setting for every Robert De Niro movie. She pays $950 a month for two smallish rooms, one of which serves as her living room and her bedroom, depending on whether the futon is open or closed. She has no full-time couch, and the decor could be described as post-IKEA, with a certain Pottery Barn influence. "I really need to move," she says, sitting in what is currently the living room. A pair of fuzzy yellow slippers lies nearby; books and CDs are piled in a corner, freshman-dorm-style; and crackers sit On the counter, taunting Mol's indomitable pet rabbit, Louis, who patrols the apartment's perimeter with a roguish swagger—the consummate Hell's Kitchen rabbit.

"Spike Lee encouraged us to improvise," she says of her role as a phone-sex operator in Girl 6. "I maybe took it a bit too seriously."

"The rabbit—that's a good thing to write about," Mol says, smiling. She straightens her blue-and-white sundress and admits to being a little edgy these days. "There's a lot with me and my situation that's kind of premature," she says. "If something's going to come a little easier, you've got to go with that. And I'm not gonna push it away—you know what I mean? But I do have these ... moments of anxiety, which is hardly surprising."

Here she is, a recently retired coatcheck girl who on her way home has to walk through men drinking malt liquor out of paper bags, and suddenly she's sizzling, hot, on the brink. Suddenly she has agents making big promises and studio execs overnighting scripts unthumbed by Winnie and Gwynnie and big-shot directors such as Abel Ferrara saying that working with Mol is "heaven on earth. I was transported, like a rainbow—a rainbow appeared in the gutter, and she was at the end of it."

For most Pre-Celebrities, these are telltale signs that the Rubicon has been crossed, and that it's safe to uncork the grappa and buy the Richard Neutra house in Los Feliz; for Mol, who has never even been to Los Feliz, yellow flags are all over the place. Don't get her wrong; she's pleased to be here—"thrilled," in fact. But still. "I was anxious because I'm going for something here, even with this," she says, meaning the interview. "You're putting yourself up for things—I'm an actress—instead of letting things take their own course. You're putting your hand in it."

She ponders the alternative—no publicity, no magazine covers, and therefore eternity in "What-If World"—and rejects it. Her mood takes a turn toward the Socratic. "Why!? Why!? Why do I have to make the decision!?" she asks herself, banging the arms of her chair. She's half kidding, half wigging. "Because it's so tempting. But then you're stuck with the consequences, whatever they'll be. Whether it's amazing and it opens doors for me or the movies don't really take off, and then"—a ghoulish expression—"everybody's going 'pffifffiftt!'" She sees it and fears it: the great Hollywood slag heap, strewn with a thousand Tanya Robertses and Richard Griecos.

So far, in a sort of pre-emptive strike, Mol is doing all the right things. She's genuinely humble ("I don't feel worthy"), deferential to colleagues she likes (Damon-mania: "totally justified"), and unwilling to tattle on those she doesn't ("That would be hurtful"). She doesn't demand to be called an "actor" ("I don't care—whatever") and is far too dignified to share her thoughts on hemp, indigenous peoples, or dolphins. Plus, she likes red meat and beer. Damon calls her "levelheaded—a good person with a good heart."

'Ohmygod," Mol says. She is responding to the one and only Gretchen Mol Rumor circulating in Hollywood—that a William Morris agent "discovered" her, Schwab's-style, while she was checking coats at Michael's, the Manhattan restaurant on West 55th Street, where the agent-publishing network converges over Cobb salad and grilled-chicken frites.

Like all Hollywood rumors, this one is half true. Yes, Mol met her agent, Larry Taube, at Michael's in 1994, when she was pulling double shifts, auditioning for Tide commercials, and hoarding bagels for dinner. What the rumor omits is that a Michael's regular, literary agent George Lane, had nagged Taube to give the kid a look, and that months passed before Taube did. "The story makes it sound like I was sitting there, waiting, as if I didn't have a life," Mol says. "He didn't walk in and go, 'I gotta give you the opportunity of a lifetime!'"

Also lost is the fact that Mol was already an actress, albeit one whose only consistent money line was "May I take your scarf, Mr. Bookman?" While studying at New York's William Esper Studio in the mid-1990s, Mol did her share of hearty New England summer stock—Godspell, Bus Stop—for which she pulled in $79.75 a week. To stay afloat, she performed the traditional struggling-actress Kabuki: waitressing, hostessing, and working for beans in a pretentious art-house theater—the celebrated Angelika, on the cusp of SoHo. There Mol was an usher, and so would gamely face down the nightly gauntlet of cineasts and N.Y.U. film-school auteurs, with their sunken eyes and dog-eared Godard on Godard paperbacks. Those were heady days. "I'd clutch the rope, take the microphone, and yell, 'Everybody—behind the red rope!' Loved that."

Mol found the job through her older brother Jim, who had himself been an usher while attending ... N.Y.U. film school. Gretchen and Jim are close. They've been this way since they were kids in bucolic Deep River, Connecticut, where they were raised by their mother, Janet. (She and Mol's father were divorced in 1983.)

On a recent Monday, Mol sat in Jim's rococo East Village apartment, perched behind a clattering 8-mm. projector. Jim, an up-and-coming film editor, took the chair; Gretchen commandeered the futon, which evidently is a Mol-family staple. They were reviewing what film scholars might one day describe as the Mols' experimental, Bauhausian phase of the early 1980s, when Jim was 12 and Gretchen 10. The first clip, from a transcendently low-tech slasher with a title card that read, "Tradically, The Girl Is Killed," showed Gretchen in her formative role: all spindly legs and Fawcettian hair, she was iced by a leering, velour-wearing madboy. The next clip was from Jim's film-school days, and was therefore disturbing and Germanic—the camera sped between Gretchen and an addled cat, filmed closeup. A third clip involved Gretchen and a can of Reddi-wip, but don't get any ideas.

Jim offered thoughtful directorial explication. To which Gretchen, red-faced, said, "All right, Jim. Let it go."

He was undaunted. She was dying a thousand deaths.

"Jim, chill."

The talk turned to a spec bottled-water commercial in which Jim cast Gretchen as the water babe. She wasn't his first choice. "You wanted someone with big breasts," she said. He changed the subject.

Nothing came of the ad, and for a while nothing came, period. Then she began landing Coke and McDonald's commercials. By 1996 she had completed an episode of Spin City, two TV movies, and a bit in Girl 6, Spike Lee's smutty phone-sex fable. "Spike looked at me with this half-smirk," she recalls. "He said, 'I know this is your first film.'" She holds up a finger, fact-checking herself. "He said, 'I know this is your first real film.'" Mol played Girl 12. Girl 7 had 13 seconds of screen time, so you can imagine. Just as well: "Spike encouraged us to improvise, and I maybe took it a bit too seriously."

Next came the role of designated crier in The Funeral, Abel Ferrara's paean to New York wise guys who wave handguns, wear pinkie rings, and rat each other out. Boy, does she cry—four minutes of heroic yowling while her man (Vincent Gallo, expertly cast) is spirited to the great unknown. You'd cry too if you were a sweet-tempered young actress thrown into a drinking, brawling frat house that included Gallo, who routinely berates fellow actors; Chris Penn, an amateur boxer and worldclass carouser; Ferrara, who curses like a sailor and makes films about sexually twisted cops; and Christopher Walken, who ... well, he's Christopher Walken.

As always, Mol is cheerfully judicious. She adores Ferrara, calls Gallo "interesting" and Walken "neat"—and, as a bonus, gives us the surreal image of Walken gently urging her to "think of Christopher Reeve" while summoning tears.

"We were looking for that look, and she had it, man—Betty-Boop-to-the-max," says Ferrara, who knew a group of guys who'd spend entire evenings jockeying over whose turn it was to hit on her. Scuffles were not uncommon. Mol handled the boys deftly, just as she did the cast. "She held her own," he says, adding that he later hired Jim Mol as his editor. "She knows how to take care of herself. She and her brother—those cats are tough."

Still, Gretchen says later, "The tears were real—let's just put it that way."

From there, she played Michael Madsen's moll in Donnie Brasco, Mike Newell's paean to New York wise guys who wave handguns, wear pinkie rings, and rat each other out. Her one juicy scene was cut, and she does not consider this a good thing: "I wish that movie was just gone." That same year Mol was cast in The Last Time I Committed Suicide, an unnecessary tribute to Neal Cassady, the lamppost-scratching Beatnik poet. Mol played a bombshell named Cherry Mary (and not for nothing). She managed to be quite adorable and perfectly convincing—more so, considering that Jack Kerouac was portrayed by Keanu Reeves.

So far, so good—and then came fatter roles in two films of the sort that film-festival publicists would term "idiosyncratic": Welcome to Graceland, in which redemption is found through an Elvis impersonator, and Music from Another Room, a love story co-starring Jude Law. Cool jobs, crummy results: both films are in limbo and probably won't be released (unless Mol becomes a star, and is thus exploitable). Mol is not thrilled about these developments either; when asked about the latter film, she grits her teeth, groans, and focuses on her rabbit, who scrams. "I shouldn't say anything," she says, learning fast.

In November, shortly before the star-making release of Good Will Hunting, she wangled an audition for Rounders, a coveted Miramax project about a reformed poker shark—played by Matt Damon—who, in order to bail out his skeezy gambler pal (Edward Norton), is drawn back into The Element. Mol was up for the role of Jo, the shark's sensible law-student girlfriend.

Mol killed. Dahl and Damon signed off on her, and her tape was sent to Miramax for rubber-stamping. Then things got freaky. Days passed. Thanksgiving came and went (and, oh, what a festive holiday weekend that was). Teeth were gnashed, cuticles chewed. "The word was, somebody at Miramax wasn't sure about me," Mol recalls. "Word was, I didn't look enough like a law student." Word was, the holdout had to be Harvey Weinstein, the company's famously imposing co-chairman. And without Weinstein, Mol knew, the message was clear: No Jo for you.

Days later, the call came. "A major actress was interested in the part," recalls Weinstein.

It might have ended that way had Mol not attended the New York premiere party for Quentin Tarantino's Jackie Brown, a film produced by ... Miramax. Mol spied Weinstein huddling with other industry heavies in a corner booth, and Sensible Girl instantly mutated. Mol cleared her throat, planted her feet in front of perhaps the most intimidating man in Hollywood, and said—firmly—"No hard feelings."

"Excuse me?" Weinstein said, mid-chew.

"No hard feelings."

"Uh, no hard feelings for what?"

"Harvey ..."

Weinstein found her bravado charming. All the more so since Woody Allen had called to recommend her.

Two days later, Mol was cast as Jo. She was eager to work with Norton, who'd made a splashy debut as the stuttering butcher boy in Primal Fear, and director John Dahl, who'd made two fine caper-noirs: Red Rock West and The Last Seduction. She was less familiar with Damon, though she'd heard he'd written a movie.

"Casting studio movies is a mystery, but at the 11th hour, we won," says Dahl, who had "no idea" who Mol was before he cast her. "She came in at the last minute, and there was a brief moment of panic. And then she settled down and took the role and seemed very relaxed and poised."

"When I did the [1993] movie Geronimo, I was hired literally the day before I left. That's a horrible feeling for an actor. It's a tremendous feeling of insecurity," says Damon. "Gretchen was put in a terrible position in that regard—but she was great. I didn't notice her as nervous at all."

Celebrity, the upcoming Woody Allen film, stars Leonardo DiCaprio, hopelessly miscast as a deified young actor who trashes hotel rooms, scuffles with paparazzi, and is catnip to the ladies. Mol plays his girlfriend. Given the film's secrecy requirements—war tribunals are more accessible—that's all anyone will say. Mol, no ingrate, sticks with the program. Then again, there's not much to reveal, since she has only the vaguest idea of what the movie is about. Cast members were never given the full script, and Allen, being Allen, betrayed little while filming. His one word of direction to Mol, however, was deliciously fraught: "Repent."

As for DiCaprio, he didn't put the moves on her, and, rumors be damned, he's no cheapskate. While filming casino scenes in Atlantic City, he endlessly slipped Mol $25-spots from a "bucket" of chips. "I regressed," she says of her DiCaprio days. "Not in the way of oggling over him. In the way of just—you feel as if you're back in high school. He'd be, like, gross. He can just be gross. At first you're like 'I can't believe this guy is acting like this.' And then you just kind of get into it."

DiCaprio and Damon: could there have been two better anthro-lab experiments for Mol? Celebrity was filmed shortly before Titanic opened, but she knew the score. "It's funny how people make reference to how he was 'nothing' before Titanic," she says. "There were tons of girls."

Damon, on the other hand, was nothing before Good Will Hunting. When Mol first met him, at the Rounders audition, "I wasn't really aware of him." Two weeks pass. He gets the frothing reviews, the big box office, the magazine covers. Then she overhears Damon getting the Golden Globes call as they are sitting in the makeup-and-dressing trailer. "You're kidding me!" he keeps saying. From then on, Mol recalls, "he seemed kind of overwhelmed sometimes. There were a lot of eye rolls—that's how we communicated. We never sat down and talked about it, but it was interesting to see. When we did the movie, he became Matt Damon as we know him." She laughs. "Whatever that means."

Damon, who calls his sudden rise to stardom an experience "in seeing how powerful the media really is," offers this bit of advice: "Don't believe the good stuff, because the inevitable backlash is right around the corner."

Not that Mol has delusions that she's about to become a tabloid-caliber superstar. (Although she did recently appear in one supermarket tabloid, which printed a paparazzi shot of her with her arms around DiCaprio. Caption: "Gretchen Moll [sic] couldn't keep her hands off handsome Leonardo.") If anything, she's thinking less Matt Damon, more Ed Norton—when she has time to think, which she doesn't. Mol recently shot a cameo in Tim Robbins's The Cradle Will Rock, in which she has one line—"Abstract Expressionism!"—and has begun filming the tentatively titled Cherry Pink, a Brooklyn-in-the-50s comedy directed by the actor Jason Alexander. Mol took the role for scale because she liked it. The only thing she regrets is the dyed-orange hairdo it requires.

"Major hair issues goin' on," she says as her rabbit gnaws at a visitor's ankle. "Louis! You're killing me here!"

Tabloid lies, problem hair, killer rabbits: welcome to Hollywood, Gretchen Mol.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now