Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

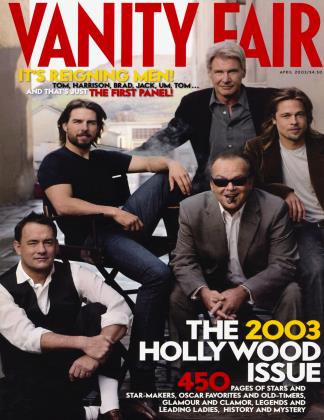

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOne of the great pleasures of editing a magazine, especially if it happens to be one like, say, Vanity Fair, is that interests that have been nibbling away at you for ages can be put to use at some juncture. Case in point: Sam Spiegel, the great circus barker of a producer responsible for such films as Lawrence of Arabia, The Bridge on the River Kwai, and The African Queen. His movies were big and so was he. Big waistline, big cigars, big parties, big suites at the Connaught—big everything. He was, in fact, all that you expect in a Hollywood producer and more. And don’t ask me why, but for the longest time I’ve been a closet Spiegel buff. A few years ago, I sailed into the harbor at Cap d’Antibes aboard a friend’s boat. He hadn’t been there in more than 20 years and said that the last time he’d visited he sailed in on Spiegel’s boat, the Malahne. Just the mention of the trip evoked all sorts of glamorous snapshots of a Hollywood I never knew but wish I had. Five years ago, I heard that Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni was working on a biography of Spiegel. And for five years I put my oar in to buy serial rights for V.F. Nonfiction books rarely get turned in on time, and this one was no exception. The book, Sam Spiegel, is finally being published this month, and an excerpt of it, “Spiegel’s Mighty Shadow,” begins on page 304.

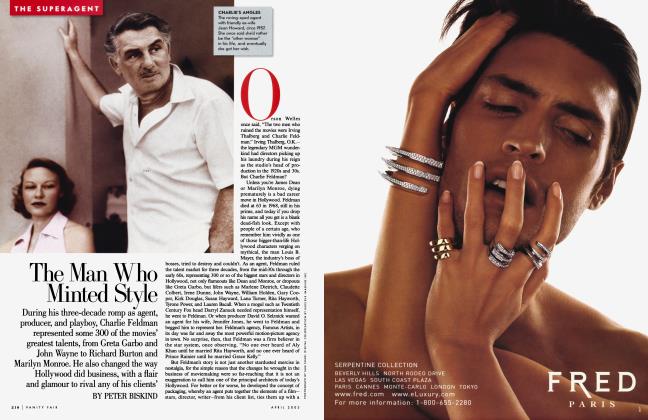

Like so many of our Hollywood Issues (we’re now on our ninth), this one is positively luxuriant in lore of that bygone time of the 30s, 40s, and 50s, when the studio system was at full throttle and movie stars drank, smoked, and wore leather shoes. Nobody took humor herself too seriously, and the movies, not incidentally, happened to be wonderful. In so many of the stories we ran in the past a name kept popping up that I had never heard before—Charlie Feldman. Peter Biskind was put on the case, and his story (“The Man Who Minted Style,” page 210) tells of Feldman’s remarkable life. He was the first superagent, a producer of such films as A Streetcar Named Desire and The Seven Year Itch, and a man with great taste and dash who dated Joan Fontaine, Rita Hayworth, and Ava Gardner. He was to the real world— that is, as real as behind-the-scenes Hollywood can be—what Cary Grant was to the actual, up-there-on-the-screen movie world.

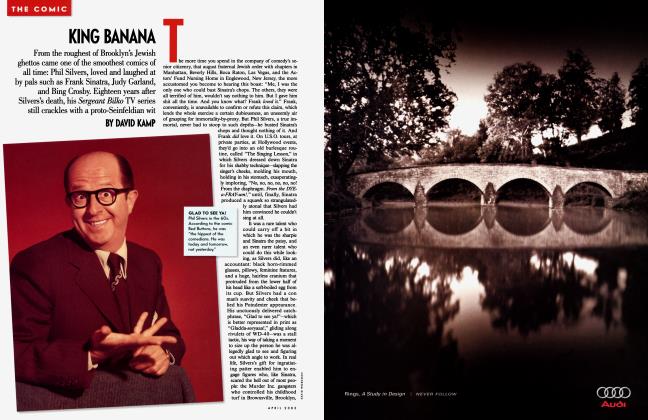

If Feldman was a recently acquired interest, Phil Silvers is an old, old one. I used to tell my children that just about everything you needed to learn in life you could pick up from watching The Phil Silvers Show—a program that holds up better than virtually anything else from the golden age of 50s TV. The show’s central figure, Sergeant Bilko, is one of entertainment’s great comic characters. Bilko was a schemer, a mountebank, and a grinning, glad-handing silver throat, but he rarely took advantage of anyone other than his fellow G.I.’s at the poker table. His heart was good, and his firefly mind was an electric, unpredictable marvel. He was Bugs Bunny to his boss Colonel Hall’s Elmer Fudd.

One of the great things I own came from a friend who happens to run MTV. It is the complete collection of the Bilko show, some 12 dozen episodes. It had been slated for a cozy second life on the then new network TV Land, but after it had been on the air for a while, the show’s demographics came up a bit short. Mostly 50-plus ex-service guys. A nice group of people, but presumably not the ideal market for advertisers trying to move sneakers and sports cars. Bilko may have gone off the air, but those tapes provided essential research for David Kamp, who produced the exquisite story on Silvers, “King Banana,” which begins on page 240. As it turned out, Kamp too was a secret Bilko fanatic. I must find out if he has any latent interest in Spiegel or Feldman.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now