Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter Forty at Sport's Peak

Many Stars Beyond the Normal Athletic Prime Have Served Youth with the Juice of the Raspberry

GRANTLAND RICE

HERE and there you hear of some doddering dodo at the ripe old age of 38 or 42 still hanging on, but in the main their plaintive cries for recognition are drowned by the clamour of the public as it thunders again that "Youth must be served."

The general impression seems to be that any man beyond forty who is still a part of the competitive menu in sport is to be congratulated, of course, for sticking around, but that he isn't to be, taken too seriously. But when you carve your way a few feet into the succulent statistics you suddenly begin to discover that the old boys are doing quite a bit more than merely making threatening gestures. There are not as many of them as there are of the younger men, but proportionately they have about as many representatives at the top as the younger generation. In the last year or so, they have been serving youth frequently, but serving it with the acid juice of the raspberry, flavored at times with the stinging aroma of crushed quince.

Some of the Shocks

THERE is a tendency among many men passing forty to believe their championship days are over when it comes to strenuous competition. But we are able to offer some slight proof to the contrary. When Stanislaus Zbyszko, the Human Consonant, was matched some time ago with young Joseph Stecher, the Nebraska Marvel, in a wrestling classic there was merry laughter from all sides.

Zbyszko, with a dome of thought almost as bald as an onion, was forty-six. And Stecher, lithe, active and youthful looking, was under thirty. Zbyszko had been thrown by Frank Gotch fourteen years ago and was supposed even then to be easing off a trifle. "Wrestling", they said, "is a tough game. The stamina and endurance of youth are big factors. The Pole's only chance is to win in a hurry. If Stecher can stick for thirty minutes it will be a mop-up".

In the meanwhile we ran into Nat Pendleton, Olympic wrestling champion, who had been training with Zbyszko. "Has the old fellow a chance?" we asked. "I don't see how he can lose," replied . Pendleton. "He's the strongest man I ever saw and quick as a flash." "But he's around forty-six," we said.

"I don't care if lie's sixty-six," Pendleton replied. "He can wrestle a week without taking an extra breath."

You may or may not recall the result. They battled for over two hours and when the final showdown came it was young Stecher who gave way to advanced years and was tossed for a field goal to the deep astonishment of the assembled populace. The big crowd present had rooted for the younger man all the way, but when the veteran finally achieved his triumph he was given what is technically known as an ovation.

For a man at forty-six to step out and defeat one of the greatest stars of all time at a game as rough and wearing as wrestling is proof enough that the old boys are not to be poohpoohed forever.

The last British Open Golf Championship was figured to be a battle between George Duncan and Abe Mitchell, both well under forty. "Vardon, Braid and Taylor, the Old Triumvirate, are through," every one said. "At fifty and fifty-one they are too old to win."

Vardon, Braid and Taylor were not close to the running. But the man who hung on grimly and gave Duncan his hardest battle was Sandy Herd, older than Vardon, Braid or Taylor. Herd was 52, but he was still young enough to come within an eyelash of winning.

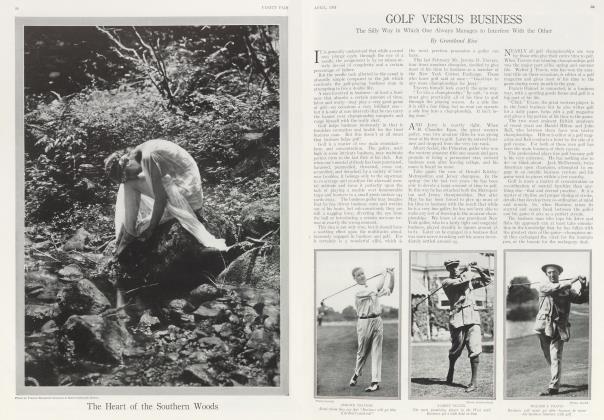

Later on Ted Ray, 43, and Harry Vardon, 51, came to the United States. As they were booked for an extended tour before the championship started, many golf experts seemed to figure they would be worn down at that age and in no condition to meet such young huskies as Walter Hagen and others. But when the final returns were in, Ray had finished first and Vardon was in a tie for second place. Here, in two of the greatest golf championships of the year—and make no mistake about the gruelling physical and mental strains of four days of medal play golf, we have,two men over fifty finishing as high as second place and one at forty-three winding up on top. And after this championship Ray and Vardon started in the next day to play thirty-six holes matches for a stretch of two months, traveling thousands of miles as they took their night's rest in Pullmans.

This slogging hike was one of the greatest physical tests of the year, a robust undertaking for a man of twenty-five, but the two old boys finished in great shape. Ted Ray is now, at the age of 44, one of the leading favorites for the next British Open which takes place late in June at St. Andrews, Scotland. And it is possible that one of the older veterans may yet step forward with another Sandy Herd surprise. This winter we had the rare spectacle of a man at 60 turning in a 68 over a standard course. This man was Walter J. Travis, still a rugged opponent to overthrow.

John Ball, Jr., and H. H. Hilton were winning championships thirty or more years ago, and yet they are still around the top. Ball won the amateur championship of Great Britain in 1888. When he went out for his eighth title in 1912 there were many hidden smiles. But, twenty-four years after he had won his first sprig of olive, he was still too strong for the younger generation, who were outclassed by his superb display.

Brookes at Tennis

TENNIS is certainly no bland and restful occupation, even for a kid. Sixteen years ago Norman Brookes was taking part in Davis Cup matches as one of Australia's leading stars. And he was no kid sixteen years ago, being then twenty-eight years old.

At the age of thirty-seven he returned to America with Tony Wilding, for the exclusive purpose of taking back the leading tennis trophy. Brookes and Wilding were opposed by two such dashing youngsters as Maurice McLoughlin and Richard Norris Williams, but the veterans carried out a successful invasion.

Then war came, bringing death to Wilding on the battlefield and active service for Brookes. He served four years with the British forces, having been twice torpedoed and left floundering at sea in the course of the war. But at the age of 44, when the strong U. S. A. combination sailed for Australia to recover the cup, Brookes again was looked upon as the main foundation of the far eastern defences. He was beaten by the brilliant tennis of Tilden and Johnston, but in each match his play was the leading Australian feature, and only the two best tennis players in the world could have stopped him.

Continued on page 92

Continued from page 61

Brookes at the age of 43, in conjunction with Patterson, was still good enough to win the world's championship at doubles. He may have lost a trifle of his early speed, but his remarkable skill is still present in copious quantities.

How is it that Brookes can play such tennis when he is several years past 40? Two main facts cover the case. He started or rather developed a strong foundation of orthodox form. And he did not bum out his vitality too soon. Bob Fitzsimmons won the heavyweight championship at 37. But Fitzsimmons received a late start and he was close upon thirty before he was known to the outside world. Young sensations as a rule come to an early finish. Most of the veterans who survive did not reach the top until they were well along.

The case of Frank Kramer should not be overlooked in collecting the triumphs of older men.

Kramer was a star bicycle rider twenty years ago. Ten years is a lengthy span for any one to hold rank in this field, where the physical wear and tear is extremely excessive. Yet twenty years after he had won his first laurels, and after he had held his championship for sixteen years, Kramer opened the new season by a dashing victory over a star field, apparently having all the speed and stamina of youth. He celebrated his fortieth birthday with a notable conquest over younger rivals who were supposed to be in full possession of his olive wreath. In Kramer's case it has been mainly a matter of careful training. He has kept himself in perfect condition, and the wonder was that he could go for any such stretch and not develop staleness. He has kept away from dissipation of any sort, has held careful watch over his diet and his time for sleep. He is now past 40 and still a star.

Pop Anson was still a major leaguer at 45, Cy Young at 44 and Hans Wagner at 43. Anson, Young and Wagner —and to this list might be added Napoleon Lajoie—were all able to prove that a man beyond 40 could still hold his place on the diamond with the picked athletes of a robust profession. Fitzsimmons, Zbyszko, Wagner, Anson, Young, Brookes, Vardon, Herd, Ray, Ball, Travis and others have lifted a beacon light of hope to those who passing 35 see the end of their competitive careers. Frequently the ensuing slump is mental, for if one begins to feel old at 40 he is likely to age rapidly. But at 45 and at 50 certain stalwarts have shown us that the human frame can still carry its share of the competitive burden.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now