Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

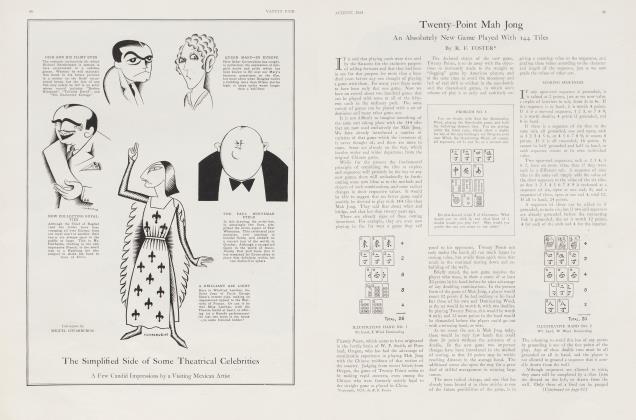

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSome Hard Luck Hands

With Some Advice on When Not to Put Too Much Faith in No-Trumps

R. F. FOSTER

Mrs. Casey-Jones

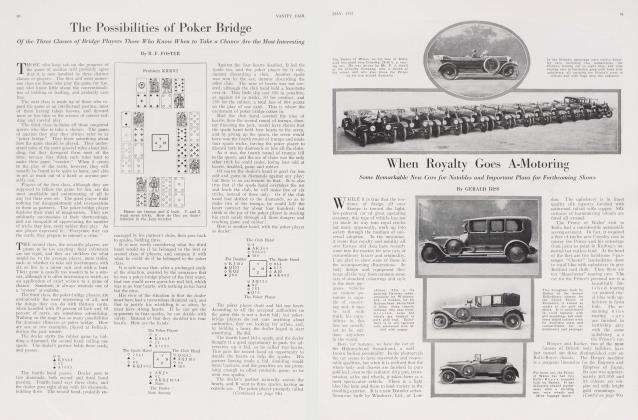

PROBLEM XXXII

Here is something for the holidays which will probably keep readers of this magazine busy for an hour or two. The beauty of the position, which is one of Harry Boardman's, is that you think you have solved it when you haven't.

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks against any defence. How do they get them? Answer in the February number.

MRS. CASEY-JONES was at the Hollywood Golf Club last October, following the championship matches in the morning and playing bridge all afternoon. On Thursday she confided to her host at luncheon that she thought there was entirely too much luck in both games.

"Sorry; but I cannot quite agree."

"Well, in golf, such trifles decide matches. Six inches higher on a brassy shot to carry a brook and Vardon would have been champion of the United Stales. Same thing this morning. If Mrs. Hall had been over that brook on her second, she would have put out Miss Stirling. If that Mrs. Brisket had not made a rotten opening against me yesterday, I should not have lost eighty dollars. It does not matter how well you bid or play, sometimes you just can't win anything. They outluck you."

"But skill will tell in the end. Been unlucky lately with those border-line no-trumpers of yours?"

"Now you know that every hand is a notrumper for one side or the other, and it's the safest bid in the game. The other side has to bid two if they want to call anything, and it encourages your partner. Bluet says eight out of ten hands played at no-trump make the contract, and six out of ten reach game. But the way luck will beat you is a crime. After luncheon I want to show you a couple of hands I played yesterday afternoon. I shall never forget them as long as I live. One of them cost me eighty dollars."

This was the first hand laid out for inspection, the dealer's cards being shown first, for an opinion on the bid.

Mrs. Casey-Jones

"I bid no-trump on those cards. All right, isn't it?"

"Perfectly."

"Well, I lost a little slam. The first diamond lead caught my lone king, and I had to make five discards. I kept two hearts, two spades and three clubs, and discarded two c.lubs from dummy. The lady to my right let go two spades and two clubs without an echo. I don't believe she knew enough to echo, anyway. The ten of hearts came next, and the queen and king drove my ace. Then I led the clubs and let in three heart tricks, king of clubs and ace of spades. Can you beat it?"

"Such things happen once in a while. It is certainly a rather unlucky hand; but they go game in diamonds if they don't finesse the jack."

"But those women won't bid their hands, and they don't know anything about the leads. Look at this hand and weep. I never saw a rotten opening do so much damage."

"I bid no-trumps on those cards. All right, is it not?"

"Perfectly."

"Well, here are the other hands. Mrs. Brisket, on my left, doubled. My partner passed. Two spades on my right. Now my partner calls three clubs. Three spades on my right. With the spades stopped and the top clubs, I went back to no-trumps. Then Mrs. Brisket doubled again and all passed. Would you believe it, I never took a trick until the finish, with the ten of hearts?"

"Unfortunate; but they could make about six odd in spades. All they should lose is one club."

"Yes, but if they open the hand" correctly I make six club tricks."

"You mean if they Open the spades. Then you don't do any more than get the odd."

"No, it was not as easy as that. I suppose Mrs. Brisket knew I had the spades stopped, so she started with a diamond; but she does not know enough to lead an honour when you have three of them, so she led a little one. If she had led the king, her partner would have to give up the jack or block the suit."

"But Mrs. Brisket can get in again easily enough."

"Yes, but her partner can't. As it was, she won the first trick with the jack and came through me with the queen of spades. Of course I didn't cover it. Then she led a small one and the ace went on."

"I think I see what is coming."

"Of course you do. Another small diamond and the queen brings in four stiff spfades, while Mrs. Brisket echoes in hearts. This made me keep three hearts, and cover the queen with the king, and then I had to throw away all my clubs on the diamonds. That put me down for eight hundred and thirty points. If they lead the diamonds correctly it would be only three thirty. There is too much luck in the game for me. I'm going to quit, it."

"Let us try them this afternoon. We might cut as partners."

"All right, let's do. I'm just crazy to get even with that Mrs. Brisket."

Concerning Take-Outs IT is certainly a curious fact, in connection with bridge, that no matter how logically certain conventions are presented, or how strongly any theory is backed up with facts and figures, there are certain people who will stick to certain plays, even in the face of demonstration that they must lose by them.

One of the most familiar of these is the habit of bidding against no-trumpers on the right, when one has the lead. Another is supporting the partner's bid on nothing but trumps, without any regard to what can be done with them. Another is calling long suits without the tops, for fear, apparently, that there will never be another chance to make a bid.

One of the most common faults is probably too great faith in no-trumpers, and the consequent objection to taking them out with a suit. "It is so much easier to go game at no-trumps". That is the usual excuse.

There has always been more or less discussion as to the holding that justifies the takeout in a major suit, hearts or spades. The writers on the game base their advice chiefly on theory, statistics being difficult to obtain. Whitehead gives four rules for the take-out, which were referred to in the December number of this magazine. The latest contribution to the literature of the game, by Walter Bluet, Bridge Fallacies, gives the result of the analysis of 100 hands, which were bid and played on three systems.

The first was the universal take-out with any five cards of a major suit. The second was not to take out the no-trumper on any consideration. The third was to take it out only when the number of honours in the suit was two more than the number of aces in side suits. He thinks the most important thing in the take-out is the honour score.

Continued on page 86

Continued, from page 67

As there are five honours, a suit of five hearts or spades headed by jack and ten would come within this rule, as there are two more honours than aces, there being no aces at all. This is about as weak a take-out as can be imagined, the odds against five cards only jack high being ten to one to start with.

The results arrived at and tabulated by Mr. Bluet are given in such a way as to confuse, rather than assist, the student; but his statement is that the restricted take-out, demanding honours or aces, went game 38 times in 100, while the take-out with any five cards went game 28 times. This gives us 66 times in 100 in favour of the take-out, as against his figures of only 42 times in 100 that the no-trumper would have reached game if left alone. In 21 cases the no-trump contract would have been set. The number of times the take-out would have been set is not stated.

In the matter of points, the notrumper seemed to show a net gain of 8,071 points if always left alone. Under the other systems, one gained 6,135 points; the other 8,722. As against this total of 14,857, the no-trumper's 8,071 in 100 deals seems to indicate a gain of about 67 points a deal in favour of the take-out, which is a much higher average than has been found in this country.

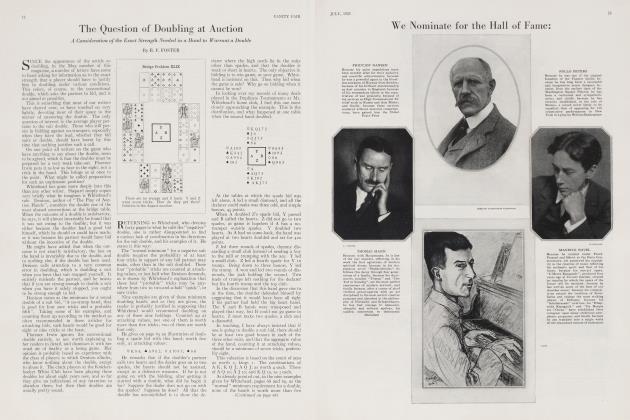

Answer to the December Problem

THIS was the distribution in Problem XXXI, which was one of S. C. Kinsey's compositions.

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want only two tricks. This is how they get them against any defence.

Z leads the diamond and the queen wins the jack. B leads the spade, Y discarding a club, when A lets the spade ten hold. When Z leads the heart, A must play the nine. A leads the winning spade, on which Y discards another club. Now, if A leads the small club, he loses a heart trick. If he leads the club king, B will lose a diamond trick.

There are several false solutions, which can be defeated by correct play. Suppose Z leads a club, after winning with the spade ten. A puts on the king and leads the winning spade. If Y sheds another club, he is down to three red cards, while B sheds a club. A club lead now forces Y to give up the best diamond or give A two heart tricks.

The heart opening will not solve, as A lets Z hold the first trick. If Z then leads a spade, A wins and leads the diamond, the queen winning the jack, and B returns the club nine, putting A in to lead the winning heart. This forces Z to give up the best spade or unguard the clubs.

If Z starts with the spade ten, A lets it hold. If the diamond follows, B wins and leads a club, allowing A to force a discard from Y with the spade jack, while B discards a club. Now B makes a diamond, or A makes two heart tricks.

If Z starts with a club, B wins the trick with the ace, and leads the spade, A letting the ten hold. If Z leads the heart, A wins with the nine and leads the winning spade, forcing the same discard from Y. If he sheds a diamond, both B's are good; if a heart, the five is good; if a club, A leads the king of clubs and Y must discard again.

IN a future article I shall deal with a new variation of auction bridge. It is called "Par" auction and is now having its initial try-outs in the city of New York. It requires special cards and special instructions but the novelty of the game is very great and I look forward with interest to its future.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now