Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOpening Interior Sequences At Auction

Avoiding the Danger of Misleading Partners in Opening Leads

R.F. FOSTER

THE tri-weekly games of duplicate at the Knickerbocker Whist Club, in New York, have long furnished abundant material for postmortems. An average of about five hundred deals a month, overplayed at least fifteen times, by players who are all notably above average, many of them nationally famous, have proved conclusively that the present standards of bidding, which have been consistently advocated in Vanity Fair, are absolutely sound. Those who have introduced new ideas, or reverted to old ones, have invariably found their scores reflect the defects of their system.

Having decided upon a perfectly satisfactory set of rules for the bidding, the cracks at the Knickerbocker turned their attention to the defects in the play. As the result of careful analysis of a large number of hands in which the final bid was the same, but the scores different, Mr. W. C. Whitehead, the author of Auction Bridge Standards, has pointed out that one of the objections to the old system of bidding, in which the same declaration might have different meanings, applies to our present system of leading, in some of its minor details.

The Danger of Ambiguity

WHETHER in bidding or play, it is obvious that ambiguity of any kind must be fatal to a partnership game. There are several modifications in the opening leads, especially against no-trumpers, which are quite modem. Notable among these are the leads from interior sequences, some of which are not yet given in any text-book on the game.

Experience has shown that certain of these interior sequence leads cannot lose, in any distribution of the higher cards; and in many cases they lead to a distinct gain. The important thing is to be certain the partner shall know that it is an interior sequence, and not the top of the suit.

Take the case of the ten lead. It is usual to lead it as the top of the sequence, 10 9 8 and others; but modem practice dictates the lead of the ten from A 10 9 8; K 10 9 8; Q 10 9 8, with or without smaller cards.

In order to avoid misleading the partner, and to distinguish a suit with four top honors against it from one which may possibly be established on the first round, Whitehead suggests abandoning the ten lead from 10 9 8, and substituting the fourth-best, so that the ten shall always be an interior sequence lead.

In looking over some of the recently played duplicate deals, here is one in which the difference between the exact information conveyed by the, new idea and the old ambiguity made the difference between winning and saving the game.

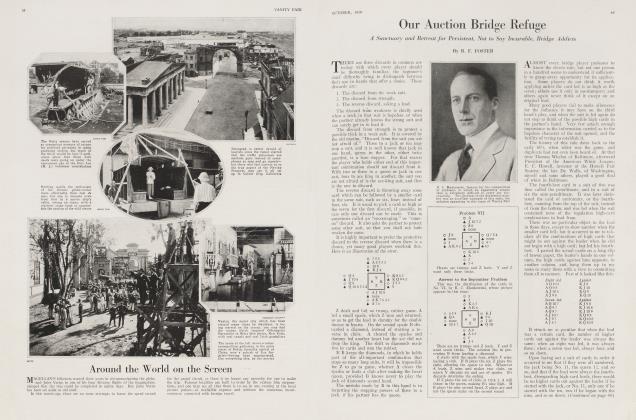

Problem XLVIII

By Professor WKRTENBAKER

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want four tricks against any defence. How do they get them? The solution will be given in the July number.

This is one of the best of Professor Wertenbaker's problems, and is an extremely elusive proposition, owing to the many possibilities of the defence.

Z dealt and bid no-trump. .Those who were not familiar with the new idea, led the fourthbest heart from A's hand. Others led the ten. B played the queen, and Z won the trick with the ace. This appears quite clear, except that the ace may be a false card. If the fourth-best were led, tie suit may have been jack high. If the ten. were led, it may have been the top of nothing.

Z led the queen of clubs and B held off. A small club brought a discard of the nine of diamonds from A, dummy putting on the ace of clubs to unblock, and coming back with the jack, which B won, A discarding the deuce of hearts.

To a player unfamiliar with the new idea of restricting all interior leads to suits containing an honor higher than the ten, it would now appear that A's heart suit were not worth much without a diamond lead from B. Accordingly, B led the diamond and lost the game, as Z made three clubs and four spades, B discarding a spade on the clubs. A return of the heart would have held Z down to two odd, instead of five odd.

The players who had adopted the new idea did not hesitate to take the very first club trick and return the heart, holding Z down to the odd trick. The original ten lead marks A as having held a higher honor, which cannot have been the jack, as J 10 9 8 was not an interior, but a complete sequence.

If this is acknowledged as being important with regard to the ten lead, it becomes even more so with regard to the jack lead. This card is at present led from all sorts of combinations, and is one of the most ambiguous leads in the game among untaught players.

The old school whist players still lead the jack or queen to show number, trusting to the second lead to show the exact holding. In the early days of bridge, Elwell suggested that the queen lead should always show two honors of some kind; and five in suit. I suggested, some time ago, the importance of exposing false cards and hold-ups by making a distinction between the lead of king and then queen to show the ace; king and then jack to show the queen and deny the ace.

When the jack is led from K Q J and others to show number, and from the top of a J 10 9 sequence, and also from the interior sequences, A J 10, K J 10, with smaller cards, the partner gets involved in a game of guess.

The advantage found by players in leading the top of the interior sequence, the jack from A J 10, or K J 10, is that if from the first, the king wins the jack, the ace and ten become a tenace over the queen; or over the king, if the queen wins the jack. If from the second, the ace wins the jack, the king ten become tenace over the queen, which is the best one can hope for.

This lead of the jack has completely supplanted the old whist lead of the ten from K J 10 and others. Many even prefer the lead of the fourth-best from K J 10 against notrumpers, the ten against a trump contract.

If the jack lead is to have only one meaning, it is obvious that it will have to be abandoned as an interior sequence lead, and that, as Mr. Whitehead suggests, the ten is the proper lead from A J 10, or K J 10; because it does not matter in the slightest, so far as the partner's understanding of the lead is concerned, whether the ten has been led from A J 10, K J 10, K 10 9 8, or Q 10 9 8.

In each of these four cases the ten lead shows the card next it in value, jack or nine, and that there is at least one honor higher than the jack, in the leader's hand. If the jack can be placed elsewhere, the leader holds both ten and nine. The placing of the nine, in third hand or dummy, will clearly indicate that the jack is in the leader's hand.

This lead is important in exposing false cards played by the declarer, or in proving that he is not false-carding, which may be equally important. The partner will know, in many cases, that it is useless to pursue the suit, unless he has some higher honor himself, as the declarer must have all the honors denied by the original lead. Here is an example:

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 79)

ZDEALT and bid no-trump, A and Y passing. B said two spades, and Z went on to two no-trumps. If he doubles, he cannot stand a weak heart take out, and he does not care to play the hand at clubs.

At the tables at which A led the jack of diamonds, B was at once put to a guess. Is this the top of an interior sequence, or the top of nothing? B unblocks, so as to relieve his partner of any doubts about the position of the queen. Z confirms B's doubt by false-carding the ace.

Z led a small club, and B won the queen with the ace, having the suit still stopped with the ten, as dummy cannot get in again to lead through him. Hoping or presuming that the original lead was from an interior sequence, K J xo, B went back with the diamond and Z was in again, A discarding another heart. Z went right ahead and cleared his clubs, getting in on the spade to win the game with three odd.

Lead Technique

THE players who had quit the lead of the jack from anything but the top of nothing, had no trouble with this deal. As the only interior sequence lead is the ten, A's jack of diamonds must be the top of nothing, and Z's ace must be a false card. Therefore when B wins the first club trick, he leads his own suit, which A did not lead in answer to his ask, as he hoped to be leading right up to two sure stoppers in spades.

Z held off, but his ace had to go up on the second round, when the nine won and the queen was returned. Now the stopper in clubs brings in three spade tricks and sets the contract, instead of losing the game.

Answer to the May Problem

THIS was the distribution in Problem XLVII, which was an illustration of the value of unblocking tactics.

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks. They get them.

Z leads the heart king, and Y plays the eight. Z leads the heart six, and Y puts on the nine, allowing B to make both jack and seven. Now B must lead a spade and Z makes two spade tricks.

By this time A is down to two cards, which must be either one diamQnd and one club (in which case Y makes two clubs) or two clubs and no diamonds, (in which case Z makes a trick with the six of diamonds).

If B gives up the heart seven on the first trick, when Y plays the eight, Z's next lead will be the deuce of hearts, on which Y puts the nine. B must take this trick or the next. If he takes it and leads another heart, Z is in with the six and gives B a spade trick by leading the ten. When B returns the spade, A is in a hole, as in the main variation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now