Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowwith Jones

James Wolcott

BOOKS

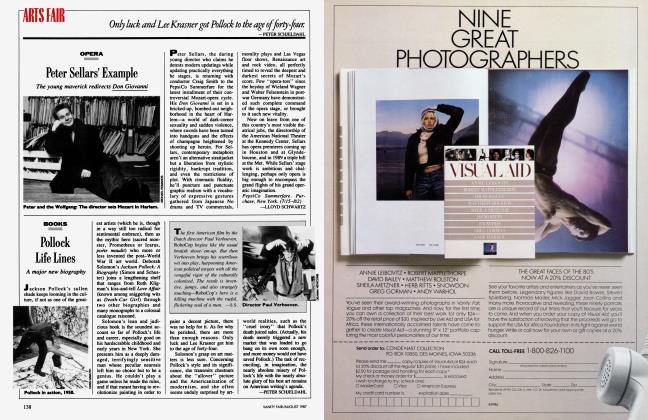

James Jones had a brow like a mallet, and he often wrote as if he were splitting rocks in a literary gulag with the business end of his skull. Prose for him was brute fact and hard labor and critics in the prison yard peeking over his shoulder, snickering. After From Here to Eternity (1951), a fortress of obsession about how men carry their loneliness into bed and battle, Jones hammered out Some Came Running, a neo-Elizabethan epic of hometown sin, The Pistol, a tightly buttoned formal exercise, and The Thin Red Line, a long infantry march that became an intricate study in fear. Even the worst of Jones's posi-Eternity novels had a monstrous grip. But if Jones never quite knew when to let go of the reader's windpipe, he was certainly more than coil and muscle. Perhaps the best portrait we have of Jones's pockets of tenderness is Willie Morris's memoir, James Jones: A Friendship, which emphasizes the violet dusk of Jones's final years in Sagaponack, Long Island. (Jones died in 1977.) But Morris's book, brotherly as it is, doesn't quite travel the full arc of Jones's career or bridge the gap between the man who created the rebel bugler Prewitt and the man who became big bwana on the Paris expatriate scene. Jones deserves a major interpretative biography, and Frank MacShane's Into Eternity: James Jones, The Life of an American Writer (Houghton Mifflin) tries mighty hard to be just that.

As a biographer, MacShane is drawn to the heavy drinkers among the heavy thinkers. He's written biographies of John O'Hara and Raymond Chandler, two men who knew how to put their elbows on the table and imbibe. Alcoholically, James Jones was no slouch. While working on Some Came Running, Jones would have dry martinis before lunch, using an atomizer for his vermouth. Drink could make Jones coarse and mean, and even when sober he liked to bang the outhouse door. He blew his nose into his fingers, and worse. "When he was introduced to a beautiful and delicate young Israeli actress, he responded by belching in her face. It was as though, in comparing her beauty and grace with his momentary

ADIS FAIR/BOOKS

idea of himself as a monster, he allowed his feelings of inferiority to manifest themselves." That's pretty much the pattern for Into Eternity: Jones belches, and MacShane fumbles in his pockets for an explanation (which usually turns out to be Freud covered with lint). Despite outbreaks of bad table manners and a tendency to blow smoke, Jones emerges as a decent, companionable roughneck, which is more a

tribute to Jones the man than MacShane the biographer. Indeed, MacShane seems to swerve out of his way to be picky and condescending. When Jones takes up sailing, for example, MacShane reports, "He had little natural grace, but he sailed correctly, as though he had learned to do it from a manual." Gee, thanks, Professor. Amusing anecdotes are scattered throughout Into Eternity, but not once does MacShane truly get under Jones's tough hide. He's like Mr. Magoo, constantly mistaking clocks for human faces.

MacShane certainly doesn't "get" Jones's writing. Although he teaches at Columbia University, when he talks about the novels of Jones and his contemporaries he's a small-town librarian passing out stale buns. He can't even make up his own mind about Jones's limitations. On one page MacShane claims that Jones wrote Go to the Widow-Maker "in an

awkward way on purpose," but only a page or so later he declares that Jones "had no facility with language." Similarly, MacShane chides critic after critic for misunderstanding and misinterpreting Jones's work ("Like many critics, [Wilfrid] Sheed completely misunderstood Jones's intentions"), yet his own summaries are self-contradicting and bland. At times he even manages to make James Jones sound as boring as James Michener in a safari jacket. Of the posthumous suc-

cess of Whistle, MacShane writes, "It more than earned back its advances and showed that Jones's public was always eager to hear from him on important subjects." Here, have a bun. My favorite unintentional laugh in Into Eternity comes when MacShane says how Elaine's was ' 'the sort of unpretentious place Jones liked, with its checkered tablecloths, familiar waiters, and good food." Good food! Even Elaine's regu-

lars have been known to rue the place as heartburn central. Celebrityhood made a king out of James Jones, but it also cut him off from his subjects (pun intended), a dilemma a less star-struck biographer might have given some digging thought. MacShane is too busy filling us in on the eats at the publication party for Whistle— striped bass and beef Florentine—to worry his head with bigger issues. Fortunately, there's currently a James Jones paperback boom—his war trilogy (From Here to Eternity, The Thin Red Line, and Whistle) has been reprinted by Laurel/Dell, and Viet Journal and The IceCream Headache and Other Stories are also hitting the racks—and readers will be able to read Jones plain without bumping into Mr. Magoo. Like Dreiser, James Jones is a great undisciplined American original whose novels, no matter how mocked or reviled, refuse to die. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now