Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDEAD COOL

Mixed Media

Thirteen years after his death, Jim Thompson's icy nihilist lit is hotter than ever

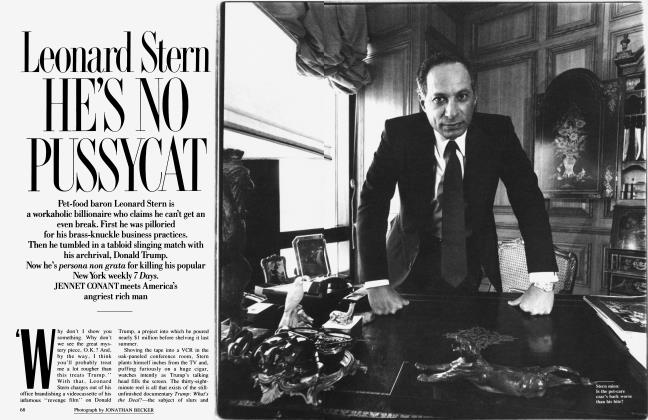

JAMES WOLCOTT

When I told a friend that a film I had just seen was based on a Jim Thompson novel, she cracked, "Everything's based on a Jim Thompson novel." So it seems. It's barely safe to pop your head out of your rabbit hole, for all the roadkill heading our way. Not that there haven't been upticks of interest before. This angular announcement that death is at hand has always had his celluloid cult. Thompson collaborated with Stanley Kubrick on The Killing. His novel The Getaway was turned into a Steve McQueen shoot-out by Sam Peckinpah. His corn-pone novel Pop. 1280 was transplanted and transformed into Coup de Torchon, featuring Philippe Noiret padding around like mashed potatoes. (Thompson's long been a favorite of the French, who like their nihilism neatly sliced.) A spate of Thompson paperback reprints in the mid-eighties inspired raves from critics who saw him as the smoking end. But all this was mere prelude to the great pileup of 1990. Three movie adaptations (with more being prepped), two forthcoming biographies, a series of paperback reissues—Jim Thompson is due to become the coolest dead writer in rotation, proof positive that America has a soft spot in the back of the weeds for its true tombstone chiselers.

He left behind a lot of handiwork. Bom in 1906, this former be 11 hop-gambler-actor-steeplejack knocked off paperback books as if they were piggy banks, racking up twentynine quickies between 1942 and 1974. Some of the titles have a humpy twitch to their hips. Wild Town. A Hell of a Woman. A Swell-looking Babe. The novels themselves read as if they were written in a tin shack at the blaze of noon to the buzz of a single fly. His lowbred, lowbrow characters haven't got a lot of book learning, but they consider themselves crafty. The men are mostly stringy meat moistened with a trickle of sweat. The women offer a somewhat fuller platter. Licking his lips, one loverboy marvels, "The good Lord had known just where to put that flesh where it would really do some good." Another man informs his mistress that if she put a raisin in her navel, she could pass for a cookie. That's about as playful as it gets in Thompson, where psychosis soon shows itself in sentences tearing themselves crazed-free from paragraphs.

True-blue Thompson fans believe that The Killer Inside Me is the best place to begin. An inspired perversity, The Killer Inside Me crouches like a sniper behind the slatted forehead of rigid, rugged propriety. The narrator of the novel is a lean, laconic West Texas law enforcer named Lou Ford who patterns himself on the likes of Gary Cooper. But his rigid posture hides his inner bent. Sly and mean, he pins poor chumps to the floor with pithy maxims ("Haste makes waste, in my opinion") until their shoes squeak from squirming. "If there's anything worse than a bore," he boasts, "it's a corny bore." A corny bore in public, in private Lou's a phony stud. After he fails to rock the bedsprings with his girlfriend Amy, he boosts himself a hormone injection. "Amy wouldn't be disappointed again," he vows. "Little Amy would be tamed down for a week." In fact, little Amy better get her butt over here right now. But there aren't any home remedies to tame the sickness (his italics) of his coiled hate. When the sickness is upon him, he strikes with fanged stealth. Sworn to uphold the law, Lou stage-manages a series of murders, which he reports matterof-factly. "By the time he hit the dirt he didn't have much left in the way of a head." The Killer Inside Me retains its original punch because it pushes its pathology past even today's readers' jaded expectations. The novel ends with a litany of the dead that binds the narrator to his victims. They're all in the same net, being lowered into the hold.

Thompson doesn't spend a lot of space on fancy motivation. The spasms of body heat in his pages are often standard pulp. (When Lou whales a woman with his belt, it only makes her hot for more. And it's not an isolated instance—Thompson's work resounds with spankings.) What distinguishes Thompson from so many male writers of the live-fast/die-hard school is the absence of erotic mystique in his mental makeup. He never elevates sex beyond the realm of sensation. A woman may be a cookie, but she isn't a chalice or a silver river; orgasm doesn't uncage his characters' souls and make the stars shimmy. At its best, sex is a temporary relief, and at its worst a permanent blight. The blight begins at birth, maybe before, somewhere back in the primordial mud. Gene-pool misfits, Thompson's men come out of the womb wobbly and never taste the reassurance of milky breasts. Unnurtured, they become unsocialized. Three days' growth of beard confirms their standing as wolfish loners, stalking the world in their cheap suits.

The Grifters is as low-down a layout of these dirt tracks as dime-store literature has ever seen. It's about a con artist named Roy Dillon, whose mother "was from a family of backwoods white trash." Roy was bom when his mother, Lilly, was thirteen; she tried to pawn him off on her family. "Then, one day, her father appeared in town, bearing

The novels read as if they were written in a tin shack at the blaze of noon to the buzz of a single fly.

Roy under one arm and swinging a horsewhip with the other." Stuck with the snot, she begrudges him the smallest consolations. Only when Roy becomes a strapping teenager does she show him a touch of tender regard, accented by "a suppressed hunger in her eyes." Lighting out on his own, Roy eventually links up with an older woman named Moira. She too was once a simple barefoot peasant. Once upon a time she and her husband lived together in Missouri and shared a version of pastoral. "It was a two-hole privy, and sometimes they'd sit together in it for hours. Peering out at the occasional passers-by on the rutted red-clay road." Sitting on the toilet, watching the traffic go by!—but I guess the good times never really do last. Now Moira flatbacks to pay the rent, amusing herself in the process. As her apartment manager sprawls atop her, she recalls the special on that day's lunch menu: "Broiled hothouse tomato under generous slice of ripe cheese."

Roy himself is trapped in an incestuous sandwich. His mother is young enough to pass as his mistress; his mistress is old enough to pass as his mother. He also beds a nurse whose placid manner belies her branded past. On her arm she bears a purple tattoo from the concentration camp where she was sterilized. Hearing her story, he babbles and shrinks from her presence as if she were infectious. He's just a small-time con.

He wants no whiff of Dachau. The nurse isn't there for shock effect. She's there to demonstrate how tightly contained Thompson's characters are even in their trespasses. That tattoo carries a shudder from a collective horror larger than any individual doom he can contrive or they can imagine. And the individual doom that ends The Grifters is a doozy. Sticking to a small canvas, The Grifters vomits a "green torrent" of money from a blood-gashed throat. On shapely ankles, incest takes a hike.

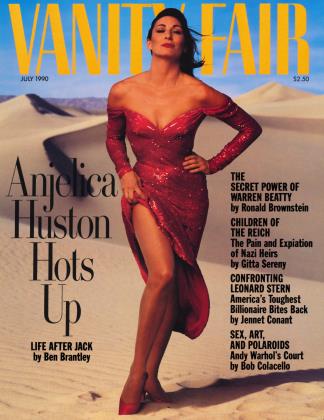

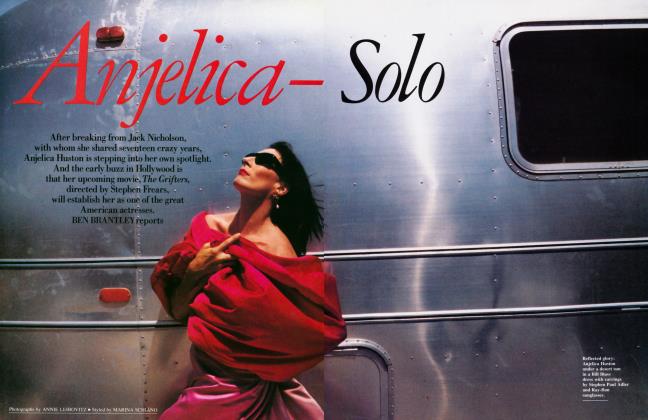

The Grifters was filmed on location in Los Angeles by Stephen Frears, with Anjelica Huston as the mother and John Cusack as the son. It will be interesting to see if the director of Dangerous Liaisons can keep a tight collar on these deviants. Because the temptation in filming Thompson's work is to expand the walled-in, warped viewpoint of his pistol packers and provide wraparound perspective and breathable airspace— in short, to "open up" the material. Although Thompson's action narratives seem a natural fit for the movies, his fatalism loses its closed-fist force when it makes its concessions to wider options. Even Sam Peckinpah shirked the craphouse hell of The Getaway, letting the outlaw lovers emerge from their premature burial with barely a scratch. Fatalism in Thompson is more than bodies slumping to the floor. Damnation is where Thompson's characters are destiny-bound. They can smell the burning crust. Another catch in adapting him is that this sense of damnation has dated. Back in the fifties and sixties, when Thompson was pounding out his page flippers, damnation was more of a dare. Today, damnation is a set designer's delight, a disco inferno. Everyone's so hung up—hell, it's as if there's no alternative.

The movie adaptation of After Dark, My Sweet pays its tribute to damnation when Rachel Ward reports that her husband is "dead. Gone to hell." But otherwise the director, James Foley, lays it on lush. Windblown drapes to signal passion, Raging Bull flashbacks with amplified blows, white migraine blinks between scenes, blackouts during the movie's one sex bout—he can't resist art-house effects. But the movie isn't a pretentious loss. What Foley captures better than any Thompson devotee thus far is the inane squabbling of Thompson's dinkhead desperadoes.

After Dark, My Sweet begins with a punch-drunk boxer (Jason Patric) shuffling into town with careful little steps, like a baby with a loaded diaper. He's fast with his fists and slow on the uptake. But he's no knockdown Neanderthal. An escapee from a mental institution, Collie is a migrant spirit of the starving class. Sizing him up as exploitable beefcake is the widow Fay (Ward), scissoring the room with her tan, toned legs. She both ropes him in and warns him against a kidnapping scheme. The "brains" behind the operation is Uncle Bud, played with dumbfounded consternation by Bruce Dem. Out of serious circulation from the movie scene, this seventies psycho makes quite a pleasing comeback as a plucked chicken in a Hawaiian shirt. When he's standing around stupid, letting the sand drain from his head to his feet, his Uncle Bud is a mall poster for shoddy merchandise. Jamming his hands into his jacket pockets as he goes off to collect the ransom money (knowing that he's going to get popped), Dern gives Uncle Bud's loser status a certain sweet poignancy. There's also a creepily soothing doctor played by George Dickerson as a cryptic closet case. (His sedated concern for Collie draws big laughs.) Unfortunately, Foley has bigger game to bag. He strives for tragic significance, staging the doomed love of Collie and Fay as something for the record books. He extracts so much pathos that the movie runs out of punk energy.

After Dark, My Sweet proves that it's best not to make too much out of Jim Thompson. After all, my sweet, he didn't make too much of himself, as witness his self-deprecating appearance in the novel Nothing More than Murder: "The Literary Club brought an author here once, and I was sold a ticket so I went to hear him. He was a big gawky guy named Thomas or Thompson or something like that, and I guess he'd put a few under his belt because he sure pulled all the stops." But now that he's a rediscovered classic, it's difficult to resist giving his stuff the full oiled treatment. Too bad. Because what Thompson's sporadic career demonstrates is how much honest turf you can cover when you're not trying to muscle up a masterpiece. Both the strength and weakness of Thompson's output is that it's so singular in temperament. It twangs its nose hairs to too few tunes'. Slumming takes you only so far. After a while you long for even a little phony sophistication. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now