Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

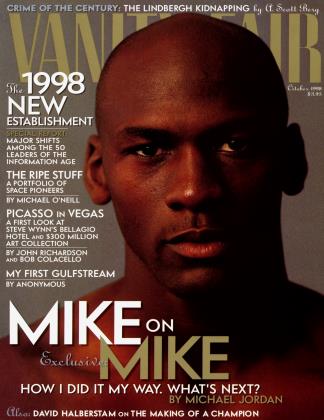

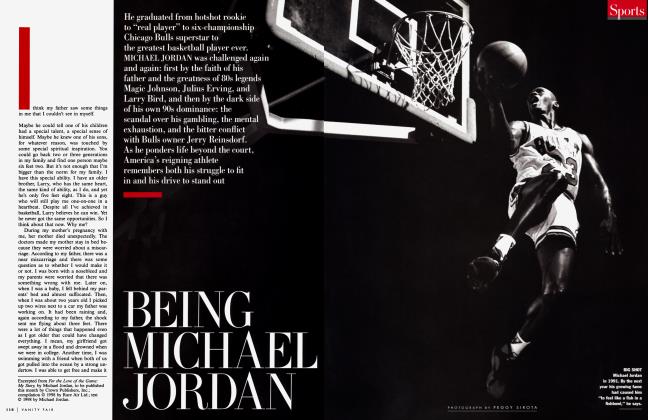

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe moment they set eyes on Michael Jordan, his coaches knew that this skinny 17-year-old high-school kid might just be the best player they'd ever seen. And one of the most powerful men in the game, legendary University of North Carolina coach Dean Smith, set out to give Jordan a future without limits

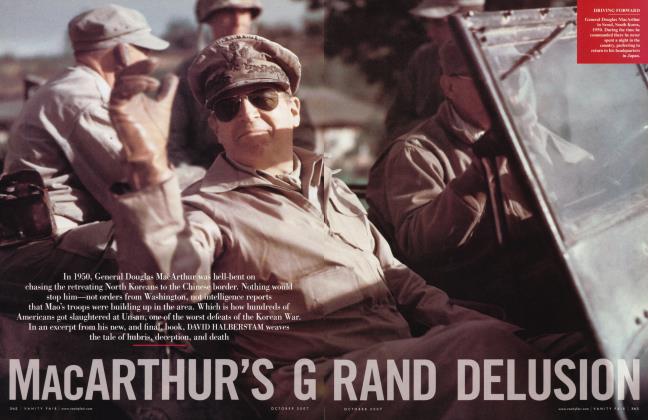

October 1998 David HalberstamThe moment they set eyes on Michael Jordan, his coaches knew that this skinny 17-year-old high-school kid might just be the best player they'd ever seen. And one of the most powerful men in the game, legendary University of North Carolina coach Dean Smith, set out to give Jordan a future without limits

October 1998 David HalberstamMichael Jordan got the chance to go to Dean Smith's basketball camp at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill in the summer of 1980, when he was a senior in high school. The camp was a big thing in the state, because only the best players were invited. Michael's pal Harvest Leroy Smith, who was six feet six inches and had made the team at Laney High School in Wilmington as a sophomore, when Michael was cut, went with him. They were paired as suitemates with two white players, Buzz Peterson and his teammate Randy Shepherd, from Asheville, in the western part of the state. Peterson was already a celebrated figure in regional high-school athletics, a candidate for Mister Basketball in North Carolina—the honor which goes to the state's outstanding high-school player of the year. Another blue-chip player at the camp was Lynwood Robinson, who had been the point guard on that year's state-championship high-school team.

Years later it would become part of the Michael Jordan myth that he had been something of an afterthought as a recruit to U.N.C. at Chapel Hill, someone whom they had stumbled on by chance at Dean Smith's camp. That was not exactly true. Michael Jordan was a late bloomer, but not that late a bloomer. The Carolina coaching staff knew from the first day of camp a great deal of what it had in Michael Jordan, and by the end of that week, though the coaches badly wanted both Peterson and Robinson, the No. 1 recruit in their minds was Michael Jeffrey Jordan. They had first become aware of him earlier that year when Michael Brown, the athletic director in the New Hanover County school system, called Roy Williams, a young assistant on Dean Smith's staff, and said he had a player named Mike Jordan, who was quite possibly the best young athlete Brown had ever seen. At first Williams was assigned to scout him, but the assignments were switched and the job fell to Bill Guthridge, Smith's top assistant. When Williams later asked Guthridge what he thought of the Jordan kid, he answered that it was hard to tell. All he had done that night was take a lot of jump shots, Guthridge said. "But he does have an extra gear," Guthridge added, meaning that at the very least Jordan had an additional bit of athletic ability which would allow him to run faster and jump higher than most kids could.

One of Roy Williams's jobs was to make sure that the best players in the state came to Smith's camp, so he called the Laney coach, Clifton "Pop" Herring, and arranged for Jordan and Leroy Smith to come. About 400 high-school kids showed up that week, players of all sizes, ages, and abilities. A handful were those that North Carolina was interested in, but most were kids of more modest talents who hoped that with a boost from the camp they might make their high-school or junior-high-school teams.

The first day was brutally hot. Williams was in charge, and he made sure everyone got to play for a little while in the Carmichael Auditorium, where the U.N.C. Tar Heels played their home games. That way, when the kids went home they could all say they had played in the storied gym. Williams had to run them in and out of Carmichael rather quickly, and he organized it as best he could—in groups of 30, which meant that he could have three full-court games going at one time.

Williams kept his eye out for this young player from Wilmington, Mike Jordan, and he introduced himself to a rather skinny young man. When Jordan's group was finished, Williams suggested he stay on for a second session. After that, Jordan left the gym, but then somehow managed to sneak back for a third session in the unrelenting heat. That impressed Williams, who loved any sign of a true gym rat. But he was impressed even more by what he saw on the court: the raw athletic ability which separated Jordan from the others there. When the workouts were finished, Williams walked back to the office of his close friend Eddie Fogler, another Smith assistant. "I think I've just looked at the best six-foot-four-inch high-school player I've ever seen," he told Fogler.

"We had decided that if we had been allowed only one player in the country that player was going to be Michael Jordan. We worked hard to conceal it."

Williams, who would go on to become one of the nation's most successful college coaches, at the University of Kansas, was stunned by Jordan's quickness, jumping ability, and defensive intensity—Jordan would simply not allow the kids he guarded to breathe. In addition he had what coaches called a nose for the ball—which meant that no matter what happened to the ball, whether it was loose off the boards or in the backcourt, he seemed to get to it a little faster than anyone else.

Of the four suitemates, it turned out that Shepherd and Jordan were in the same group, while Peterson and Smith were in another. Each day Shepherd would report back to Peterson about Jordan and each day his enthusiasm escalated. "Hey, that guy Mike in the connecting room, he's a really good athlete, and he can really jump," Shepherd said the first day. The next day it was "He's a great athlete," and the third day it was "Buzz, you can't believe what it's like to play with him—you just throw him the alley-oop and it's gone." He doesn't like to play outside much, Shepherd told Peterson, but inside he's a killer because he's so quick and because he's such a great jumper. By the fourth day he told Peterson, "You and I have never seen anything like him. I think this guy can play in the N.B.A."

The four suitemates—two of them black, two of them white—were very much at ease with one another, hanging out after practice, going to eat together. Peterson was taken with Jordan's ebullience. He seemed naturally joyous. He loved basketball, and because basketball was his life he loved life. He talked a big game, but it was done with such childlike innocence that the effect was not one of arrogance, but of sweetness. Years later, when Peterson became a college coach himself, he understood better what Michael had been going through that summer, the explosion of talent and belief in his abilities. Throughout his adolescence he had been fighting his size; suddenly he had spurted to six feet four inches. He was pushing himself to his limits, and finding that so far there were no limits. "He knew that he was going to get better," Peterson recalled, "and for the first time he had a sense of what the future might bring for him—and he was in love with it."

Soon the other coaches—Dean Smith, Bill Guthridge, and Eddie Fogler— were all seeing the same thing Williams was. "We had decided that if we had been allowed only one player in the country," Roy Williams remembered, "that player was going to be Michael Jordan. We worked hard to conceal it because he was not yet well known and we wanted to keep it that way. But it was also clear he was the best player there. And we knew he was going to grow into that body and that he was just going to get better—how much better we did not know."

Nevertheless, word on Jordan was already beginning to leak out. Doug Moe, who was then the Denver Nuggets assistant coach, had come back to the camp for a visit that summer, as Carolina alumni were wont to do. One day he called his pal Donnie Walsh, also a member of the Carolina inner club and his boss at Denver.

"How's Worthy?" Walsh asked, because James Worthy had just completed his freshman year at Carolina and was already being talked about as a superstar-in-waiting.

"Forget it," Moe said. "There's someone here who's going to be a great player."

"Who's that?" Walsh asked.

"A kid named Jordan. Mike Jordan."

"He's that good?"

"Donnie, I'm not talking good. I'm talking great. I'm talking Jerry West and Oscar Robertson [the two legendary guards of the era]," Moe said, which impressed Walsh because Moe was a tough grader.

After the weeklong camp was over, Roy Williams helped arrange for Jordan to go on that same summer to Howard Garfinkel's Five-Star Camp near Pittsburgh. It was not an act which pleased Dean Smith greatly. Pop Herring, knowing now that he had something of a star on his hands, had asked Williams whether Michael should go to one of the teaching camps for outstanding high-school players, and Williams had decided to be straightforward about it. Yes, he should go, he had answered, and the best of the camps was the one run by Howard Garfinkel and Tom Konchalski. The coaching there, Williams thought, was simply superb, with many of the best high-school and college coaches in the country participating. Williams called Konchalski to tell him about Michael Jordan, and to ask if there was a place at the camp for him.

Dean Smith was more than a little irritated with Williams for going ahead and placing Jordan in the camp. "Why'd you do that?" he asked. Williams answered that it was inevitable that Jordan would go, so why not act as a broker and strengthen the connection with his high-school coach. But clearly Smith saw no particular advantage in letting other coaches view this young man in a showcase setting. Still, Williams believed he was doing the right thing: a player like this was not going to remain a secret much longer, and he hoped his good deed would one day be repaid. Two of the players whom North Carolina had recruited for its incoming class, Sam Perkins and Matt Doherty, had played at Five-Star, and there was a cordial relationship between the camp and the North Carolina coaching staff.

At Five-Star the names of the top players were put in a pool, and the coaches drafted them for their teams. Brendan Malone, then an assistant coach at Syracuse and later an assistant coach for both the Detroit Pistons and the New York Knicks, was set to coach there, but his wife had been in a minor motorbike accident, and he had to come late to the camp. He had asked Konchalski to draft a team for him, giving specific instructions: he wanted Greg Dreiling from Wichita as a big man and Aubrey Sherrod, a highly touted shooting guard also from Wichita, as his two guard. When Malone arrived a day later he asked Konchalski if he had taken Sherrod. No, said Konchalski, I drafted a kid from North Carolina named Mike Jordan. Malone was furious. "Who the hell is Mike Jordan?" he asked. "Brendan," Konchalski answered, "I don't think you're going to be disappointed. In fact, I think you're going to be very happy."

Jordan was thrilled to be at Five-Star. He had flown up to Pittsburgh with Leroy Smith, and they had both been exhilarated and terrified. It was one thing to go to Dean Smith's camp in Chapel Hill, where their high-school coach already had some connections; it was another to get on an airplane and go to a camp where all the best players in America were going to be, the kind of players who were already being written about in the basketball magazines.

Somehow the figure 17 had reached them, the fact that there were going to be 17 high-school all-Americans at the camp. Some of these players were said to have received 50, 60, or even 100 letters from interested colleges—so many that they had to stuff the letters into shoeboxes.

But fear on the plane ride was mixed with anticipation: this was the make-or-break moment, the moment when they might rise to the better schools and live out their dreams. Leroy Smith's father was a welder for the Navy and his mother a seamstress; if he did well it would take the pressure of paying for a college education off them.

Howard Garfinkel was like a tout in the world of horse racing except that instead of touting horseflesh he touted young basketball players; his great skill was to be able to pick up on a young undiscovered player and tout him to the world, so that people would later say that he had been discovered at Five-Star. Garfinkel talked like a character out of Damon Runyon, and his office in New York, fittingly enough, seemed to be a back-room table at the Carnegie Delicatessen. Later, Garfinkel would say of that week that a star had been born. He remembered the moment when the draft was about to start. Everyone had expected Konchalski to select Aubrey Sherrod, but he had picked Michael Jordan instead. Determined to see what this kid from North Carolina was like, Garfinkel arranged his schedule so he could watch Jordan's games. All he needed, he later said, was to watch three possessions. Actually, he amended, he needed only one possession. Jordan was playing defense, and he stripped the offensive player of the ball and drove down the court. He did not dunk, because dunks were not allowed at Five-Star (this was a teaching camp and there was a fear that a kid might get hurt going for a dunk, and, even more important, a belief that if the kids were allowed to dunk they would come to view it as their ticket to the next level), but had raced ahead, with as explosive a burst of speed as Garfinkel had ever seen, and then, as he approached the basket, slowed slightly and laid the ball in with a gentle finger roll.

Garfinkel watched a few more possessions and was amazed: Michael Jordan was quicker than anyone else, he had great jumping ability, and yet he played in control. That was the most surprising part. Most young kids with that kind of athleticism, Garfinkel thought, tended to play wildly, as if they believed that athletic talent was an end in itself. But this kid had a degree of polish to his game which belied his years.

Even as Jordan was playing, Garfinkel went to the phone and called Dave Krider, a friend also in the touting business. Krider was in charge of the high-school all-American selections for Street & Smith's, the bible for colleges looking for the best young players. Here was Jordan, playing with nine other talented players, almost all of whom had had more coaching than he and several of whom were already being avidly courted by top colleges—and yet he was taking over the game. Garfinkel watched as Jordan blocked three shots and made two steals. "Dave, I'm watching something extraordinary. I've got a great young player here. His name is Mike Jordan. He's amazing. Do you have him listed?" Krider checked and said that he had never heard of him. "Well, he's one of the top 10 players in the country. You've got to get him on one of your two or three all-American teams. If you don't, everyone's going to make fun of you."

Krider called back later to say that his listings were all locked up and it was probably too late to change them, but he would talk to his editor. (Krider, in fact, eventually checked with the man who had done the regional spotting for him, a man with strong Carolina connections. The agent had deliberately left Jordan off the list of the top 20 players in the state, a furious Krider decided, because he wanted to keep other colleges off Jordan's trail.) Garfinkel called one more time to push Jordan: "Tell your boss, even if it costs $100 to make the change, it's worth it because the kid's going to be a great star." But it was too late for the listing. Later that day Garfinkel spoke to Jordan, telling him he had tried to get him on the high-school all-American listings but he had been too late.

It was a great week for Jordan. He was M.V.P. of the league and M.V.R of the all-star game. Brendan Malone fell in love with him, not just because of his abilities, but because he was so receptive to coaching. Nothing would be better than to bring him to his school, Syracuse, Malone thought, but as he watched Michael go to the various instructional stations each morning, he noticed one thing: wherever he went there was a shadow, and the shadow was a big one, because it was cast by Roy Williams, or some other Carolina coach. Someone from Carolina was always there.

When the week was over, there was a decision that Jordan had played so well that he should stay another week. Buzz Peterson arrived for Jordan's second week. By that time the only person anyone at the camp was talking about was Jordan. Peterson and Jordan got closer during their week at Five-Star; they played against each other in the one-on-one championship, and Jordan won in a close game. But they liked each other, and Jordan suggested that they go to Carolina and room together. "We could win a national championship together there," Jordan said, and with the innocence and enthusiasm of youth, Peterson immediately agreed.

The recruiting was heavy that year for both of them. But in the end, given the awesome hold Dean Smith and the U.N.C. program had on the state, it was extremely difficult to steal a great high-school player from North Carolina. At one point Brendan Malone called Jordan to ask if he would like to visit Syracuse. "Coach, I really liked playing for you," Jordan answered, "but I've already made a decision to go somewhere else." "I think I know where it is," Malone said. "Good luck anyway, Michael."

In addition, Jordan's parents, James and Deloris, were fond of Roy Williams, who had made the first connection with Michael and who kept in touch with them. In those days Williams was the lowliest of the low on the Carolina staff, a graduate assistant. He did all the scut work and was paid a meager salary: $2,700 for the first year, and $5,000 by the time Michael Jordan arrived. (In years to come, one of the reasons that Jordan remained intensely loyal to the Carolina program was that men like Williams made such sacrifices when he was there, working bone-crushing hours as assistant coaches earning tiny salaries.)

A former military man then working for General Electric, James Jordan enjoyed the company of Roy Williams immensely, and his wife later told the coach, "Ray [her private name for her husband] really likes you because he thinks you work so hard for your money, and that always appeals to him. It's the way he sees his own life." During Michael's last year in high school, Williams told James Jordan about how he liked to chop wood, both for the exercise and for the fuel; he wanted to get a woodstove for his house to cut back on his heating bills. A bit later James Jordan called Williams and asked for the measurements of his fireplace. A few weeks after that Jordan drove up to Williams's house with a woodstove which he had made himself. When Williams tried to pay him, Jordan got irritated. "Coach," he had said, "I'm really tired from finishing it and hauling it up here and bringing it in the house. If I have to carry it back out, and take it all the way back to Wilmington I'm going to be very angry." If the N.C.A.A. had somewhat Draconian rules about players' accepting gifts from coaches, it had none about assistant coaches accepting homemade woodstoves from parents, and the stove stayed. When Williams moved to a better house as he rose in the Carolina hierarchy, James Jordan made him a new woodstove. In 1988, Williams took the Kansas job, and he sold his house. The buyer asked what kind of woodstove it was. "Is it a Fisher?" he asked, mentioning a prominent maker of woodstoves. "No," Williams answered, "it's a Jordan."

Bob Ryan, the doyen of American basketball writers, once noted that Dean Smith did not so much recruit his players as select them—meaning that his program was so rich, the dynamic of it so powerful, that he, unlike other coaches, had the luxury of taking only the players he wanted. In 1981 when Michael Jordan arrived on campus as a freshman, Dean Smith was at the apex of his power and reputation, and his program was considered the best in the country, even if he had yet to win his first national championship.

Visiting coaches and players who were accorded the honor of being allowed in to the Carolina practices were always struck by a number of things. The first was how quiet it was. There were no sounds except the noise made by a bouncing basketball, or the occasional yell of "Freshman!" when a ball went out of bounds (as low men in the hierarchy, freshmen, not managers, had to retrieve errant balls), or the blast of a whistle, which signified the end of a drill. Another thing was how brilliantly organized the practice was, with a schedule posted each day which outlined how every minute would be used. Rick Carlisle, who played against Carolina in his years at Virginia, and who was later let in to see a Carolina practice as an assistant coach in the pro game, thought watching the Tar Heels was a revelation. Not only was practice mapped to the second, but there would be a manager standing alongside the court holding up his fingers: four meant four minutes to go in the drill, three meant three, and so on. No wonder the Tar Heels always seemed so calm and collected in games, despite the frenzy in the gym, Carlisle thought. The answer was right here in the way they practiced each potential game situation, how they would play, for example, six points behind with four minutes left. Nothing was ever to surprise them, and almost nothing, Carlisle thought, ever did.

Jordan was, thought his Carolina teammate James Worthy, like a friendly little gnat who was always buzzing around, boasting of what he was going to do.

No one was to be late for practice, for they were never to be behind schedule. All the players set their watches to what they called G.S.T., which was Guthridge Standard Time, in honor of Bill Guthridge. In Jordan's freshman year, the team bus was leaving for the Atlantic Coast Conference championship at the appointed minute as a car pulled up. The car contained James Worthy, the team's star, but it had been held up at a red light. The bus, the team members noted, left exactly on schedule, and Worthy had to follow in his car, knowing that he was in for some tough disciplinary words.

If a player drew a technical foul during a game, at the next practice he was forced to sit on the sidelines drinking a Coke, while his teammates ran extra sprints to atone for his sin. Over the years not many Carolina players drew technical fouls. Everything in the Carolina program had a purpose, and the purpose was: to teach respect for the team, respect for authority, respect for the game, respect for opponents. Smith's players were never to do anything that would diminish an opponent. Once, when Carolina played a weak Georgia Tech team and was ahead by 17 points, Jimmy Black and James Worthy combined on a showboat play in which Black flipped Worthy a behind-the-back pass and Worthy dunked. Smith was furious, and immediately yanked both players from the game. "You don't do that," he said, truly angry, "you don't show people up! How would you like it if you were down 17 points and someone did that to you!"

Dean Smith's boys were to go to class, and their attendance was closely monitored. They were also to attend church unless they had a note from their parents saying they did not go to church at home. There were all kinds of lessons which had nothing to do with basketball. Lessons on how to talk to the media, how to look reporters in the eye when you speak to them, and how to know before you start to talk what you want to say. The players were taught how to dress and how to order in a restaurant, and how to stand up when a woman approaches the table.

Some high-powered athletic programs at major schools have formidable holds on the alumni and undergraduates, but the players themselves come away feeling disillusioned and exploited. The Carolina program was different—the greatest loyalists were the players themselves. Former Carolina players in the N.B.A. returned every summer to get in shape by working out with the team. Men in their 40s and 50s still referred to Dean Smith as "Coach," and made no career moves without checking in with him.

"The Dean Smith thing at North Carolina is like a cult," said Chuck Daly, the former Penn, Detroit Pistons, and 1992 Dream Team coach. "Most cults are bad, but this is the rare good cult. But it's a cult nonetheless." Or as Kevin Loughery, a former N.B.A. coach in several cities and Michael's first professional coach, added, "I'm struck by the loyalty, the reverence of so many truly accomplished grown men for Dean Smith, the sense that their feeling about him is absolutely genuine. Maybe the great thing about him is that he treats the 12th man on the bench as well as he treats his stars. And the kids know that and they learn from that."

Above all at Chapel Hill, the concept of team absolutely overshadowed individual ability. There was a great belief in the professional ranks that the Carolina system suppressed individuality, but James Worthy explained it differently: the system was designed not so much to reduce athleticism and individuality as to reduce risk. The ball was always to be shared. The purpose was to create good shots for everyone. That meant a superlative athlete, an obvious all-American who at any other school might get 25 shots a game, would get only 12 or 15 at Carolina. (In his last year at Carolina, on his way to being a consensus all-American and the No. 1 pick in the entire draft, Worthy averaged 10 shots and 15.6 points a game; Michael Jordan, who would ring up seven seasons in a row as a pro in which he averaged 30 or more points a game, averaged 19.6 a game.) It was sometimes hard for pro scouts to tell how good Carolina players were, because the program at once made certain players look better than they really were and hid the talents of great individual stars.

By the 1980s, the salaries of basketball players were escalating ever higher, and since many young players intended to stay only a year or two in college before signing lucrative pro contracts, they would choose colleges which would best showcase their individual abilities; they listened to the siren songs of coaches who promised them that from day one they would be the main man and the offense would be built around them. That meant that the value system Dean Smith had so carefully constructed over some two decades at Carolina was in danger of becoming an anachronism by the time Michael Jordan arrived there. But Jordan, raised in a highly disciplined family, was comfortable in Smith's hierarchical system. He played within the Smith program, and in fact played happily within it, but nevertheless there were constant sightings of just how incredible he was—a burst of speed on offense and an exceptional move to the basket, or a dazzling defensive play. By the middle of his freshman year, there was growing word among aficionados of college basketball about an incredible young kid at Carolina, playing on a team already loaded with stars.

He simply hated to lose—even in Monopoly games. If Jordan fell far behind, he was capable of sending his opponents' hotels and houses crashing to the floor.

Dean Smith brought him along slowly—though far more quickly than he probably wanted or might have done in another age—but he never bent his program to suit him. Rather, Smith made Michael work his way to stardom. He would have to earn everything. He would have to excel at the hard, gritty work of practice drills and thereby become an infinitely more finished and more complete player, and, perhaps even more important, a player who, for all his wondrous natural talent, respected authority. The last would make it easy for later coaches to reach him.

It was an ideal situation for Jordan at Carolina. He did not have to carry the team, and he could learn without being at the center of the program. Nevertheless, in his freshman year he earned the right to start, albeit with certain restrictions. Sports Illustrated, knowing that Carolina was loaded, that it was a unanimous pre-season pick for No. 1 in the country, asked Dean Smith to put the starting team on its cover. Smith reluctantly agreed, but with one condition: the magazine could have four of his starters but not the fifth, the young freshman from Wilmington. "Michael," he later explained, "you haven't done anything to deserve the cover of a magazine. Not yet. But the others have. So that's why I don't think you should be in the photo." Dean Smith had handled the crisis masterfully, his assistant Roy Williams decided; he had not so much denied a talented young player an honor, as issued him a challenge— and this to a young man who, more than anything else, loved challenges. Later, after the team won the championship, an artist's sketch was made of the magazine for a poster, with the likeness of Michael Jordan added.

Dean Smith was, the other coaches and some of the players thought, if anything, a little harder on Michael in practice than he was on the other players. The other coaches also pushed to drive him to a higher level. Roy Williams was always pushing Michael to work harder in practice. "I'm working as hard as everyone else," Jordan would answer. "But, Michael, you just told me you wanted to be the best," Williams reminded him. "And if you want to be the best, then you have to work harder than everyone else." There was a long pause while Michael pondered what Williams had just said. Finally he replied, "Coach, I understand. You'll see. Watch."

Jordan's teammates were beginning to get a sense of how good he was. Yes, he talked big, and there was a certain youthful cockiness, but they had learned that he could back it up. He would talk big and then play big. Worthy, who was already all-American, thought he was like a friendly little gnat who was always buzzing around, boasting of what he was going to do. You'd swat him away and then he'd come buzzing right back at you, boasting a little more. Tenacious as hell. Every day in practice there would be a moment when they saw a burst of his amazing talent. There was one early practice in his freshman year when he astounded everyone with one of his moves: he drove down the lane, and Sam Perkins came out to stop him and make the block. Michael switched the ball to his left hand to keep it away from Perkins, but that gave Worthy, who was just behind Perkins, an excellent chance to stop him. But even as Worthy moved toward Jordan, Jordan went by Perkins and twisted his body in a way to cut off Worthy's angle on the ball; then he shot from an impossible position, turning his body away from the basket to protect the ball. The ball went in anyway. No one had ever seen anything like it. It was impressive, not the least because it was done against two great players who would both be all-Americans. Practice did not stop, because practice never stopped at Chapel Hill, but it was a breathtaking moment and later everyone was talking about it in the shower and at dinner. Worthy was astounded at the body control, the ability to adjust. But what he remembered most was that it had all been pure instinct, that Michael had been able to make up his mind and have his body obey in the microseconds after he had left the ground.

It was in the 1982 N.C.A.A. championship game against a powerful Georgetown team that Jordan first captured the imagination of America's sports fans, hitting the winning basket, a 16-foot jump shot with 15 seconds left and his team behind. It was a big-time basket in a big-time game—and he was just 19 years old. But there was a move he made earlier in the game which would become, if anything, even more of a Jordan signature play. It was a drive he made against Patrick Ewing, then the most intimidating player in college basketball. With about three minutes left, Carolina, leading 59-58, went to a slowdown version of its offense, to run down the clock. Suddenly Jordan saw the faintest glimmer of a lane to the basket, and he went for it, angling his body as best he could away from where the defense would come. As Jordan neared the basket, Ewing jumped out to make the block. Jordan, in the air, moved the ball from his right hand to his left, and flipped it up, just over Ewing's outstretched hand. The ball floated up ever so softly, so high that for a moment it seemed it might go over the glass. "He put that ball up 12 feet," said Billy Packer, one of the announcers. On the bench, Roy Williams was sure that he had laid it up too high. Instead, it hit the top of the glass, fell gently off it, and dropped down through the net.

He was different after that game, his friends and coaches thought. As his sophomore season was about to begin, there was a new confidence to him. It was, thought Buzz Peterson, as if for the first time Michael Jordan understood that he could be not just good, but great. That he had gone to a different level was obvious to his teammates; in September, during the four-week period when everyone—the previous year's players, incoming freshmen, and alumni now in the N.B.A.—came back to Chapel Hill to work out and get in shape, he was the dominant player on the court, scoring regularly on seasoned N.B.A. stars. He had returned bigger, stronger, and faster. To the pleasant surprise of the coaches, he was still growing. Roy Williams had measured him at six feet four inches as a freshman, and now, a year later, he was six feet six inches. Among other tests the players had to undergo each year on the first day of practice was a 40-yard sprint. The previous year he had run the 40 in 4.55, which was good, but now, a year later, he ran it in 4.39. That was the kind of speed only the fastest athletes in the world could match—Olympic-class sprinters and N.F.L. cornerbacks, athletes for whom pure speed was an end in itself.

That fall, Billy Cunningham, one of Dean Smith's first great players, and at the time coach of the Philadelphia 76ers, dropped by his alma mater and watched a practice. Afterward, he turned to his old coach and said of Jordan, "He's going to be the greatest player ever to play at Carolina." Smith, eager to protect Jordan from just that kind of speculation, and wary of damaging the egalitarian ethos of his program, snapped back, "No! We've had a lot of great players here! Michael is just one of them!" But, nevertheless, Cunningham thought, Michael was better than the others; there he was, starting his sophomore year, doing things which could not be taught, things which he was inventing.

Jordan's teammates came to realize that he was driven by an almost unparalleled desire—or need—to win. All top athletes are driven, some more than others, but Michael was the most driven of all. He simply hated to lose, on the court in big games, on the court in little games, in practice, even in Monopoly games with friends. (If he fell far behind in Monopoly, he was capable, with one great sweep of his arm, of sending his opponents' hotels and houses crashing to the floor. Farewell to the Boardwalk.) In card games and billiards his passion for winning was just as strong—so strong that he sometimes tried to change the rules to fit his circumstances. A pool shot which he had missed did not count because someone had spoken just as he was about to shoot, for instance.

Every competition had the quality of a life-or-death struggle for Jordan. In his sophomore year the Tar Heels went to Atlanta for a game against Georgia Tech, and Roy Williams, as the youngest assistant coach, was assigned to do bed checks. It was late at night, and he knew the players were in the hotel's game room, so he went there. Michael was drilling everyone in pool, having a wonderful time, lording it over those he had vanquished. Williams joined the laughter, at which point Michael challenged him as well: "You're laughing, Coach. Well, I can handle you too. Come on, take a stick." They played three games, and Williams, a very good pool player, won every one. When it was over, Michael would not speak to Williams. Nor did he speak to him a little later, when Williams conducted the bed check; nor did he speak to him the next morning at breakfast. Later, on the team bus, Williams was on one side of the aisle and Eddie Fogler was on the other. Williams had not mentioned the previous night's pool game to Fogler. Michael got on the bus and went right past both coaches, obviously shorn of his normal ebullience, and Fogler, sensing some kind of anger there, said, "Hey, Michael, what's the matter—Coach Williams beat you in pool last night?" Jordan, obviously irritated, turned to Williams and said, "You told everyone!" "Michael," Fogler said, "Roy didn't tell anything to anyone. I could tell from looking at you what happened. The defeat is on your face."

Then there was golf, which Michael was just learning that year. One day he played with three friends: Jordan and David Hart, the manager and a roommate for the season, against Peterson and Matt Doherty, another teammate. It was a close game with a lot of woofing, and when it came to the final hole it was winners take all. Three of them drove to the elevated green, but Michael's shot went over the edge and back down behind. As a novice, he needed nothing less than a miraculous chip shot. Which he hit, winning the match for his twosome.

When they got back to their room Hart congratulated him and asked how in the world he had managed to hit it. Michael looked around as if to make sure that no one else was in the room. "I didn't hit it," he said. "I just threw it up on the green."

The key to Michael Jordan's fierce competitiveness, friends thought, lay in his rivalry with his older brother Larry. A formidable athlete in his own right, Larry Jordan was too small to achieve in sports what his heart, will, strength, and natural talent would normally have earned him. "He was a stud athlete," Doug Collins, Michael Jordan's third professional coach, once said. "I remember the first time I saw him—this rather short, incredibly muscled young man with a terrific body, about five feet eight inches, more a football body than a basketball body. The moment I saw him I understood where Michael's drive came from." Or as Pop Herring once said, "Larry was so driven and so competitive an athlete that if he had been six feet two inches instead of five feet eight inches, I'm sure Michael would have been known as Larry's brother instead of Larry always being known as Michael's brother."

"Michael's older brother Larry was a stud athlete... this rather short, incredibly muscled young man. The moment I saw him I understood where Michael's drive came from."

For years, Larry, with this tremendous strength, could dominate Michael, and as a result it was nothing less than fierce athletic combat out there every day in the Jordan backyard—the two brothers banging up against each other on the small basketball court their father had built. Then, before his junior year, Michael shot up, became much taller, and the balance changed. Their father, Michael believed, tried to balance things out by complimenting Larry more for his athletic accomplishments. "If I scored 25 points in a game and Larry had two steals, somehow my father would make it even." If anything, Michael added, that drove him to work even harder on the court.

Dean Smith was the one who thought it was time for Jordan to turn pro after his junior year. One of the great strengths of Dean Smith, his players believed, was that he always did what was best for the players, and the best thing for Michael Jordan was to turn pro. There were no more worlds to conquer in the college game. His team had won a national championship. He had been college player of the year twice, he had won the Naismith Award, and he was an all-American. The defenses were keying on him now, throwing zones and double teams at him, and Smith sensed that the senior year would be more difficult. To the degree that he could be coached at the college level, the job had been done. Now it was time for him to adjust to a different game, one with perhaps less discipline but with more speed and greater individual challenges. The danger if he stayed in college was that he might sustain an injury that would seriously affect his professional price, which was likely to be high. Smith had started checking to find out where Michael might go in the draft. Billy Cunningham, a Tar Heel true and blue, wanted him for Philadelphia. Soon it became apparent that the worst scenario had Michael going to Chicago as the No. 3 pick. The beginning salary would probably be at least $700,000 a year, perhaps more, and the contract would be for at least three or four years.

It was emblematic of the values in the Jordan family that even though Michael was about to become a millionaire his mother was uneasy about his leaving school early. She had always cherished the dream that Michael and his sister Roslyn would graduate from Chapel Hill on the same day.

Dean Smith finally had to persuade her: "Mrs. Jordan, I am not suggesting that Michael give up his college degree. I am only suggesting that he give up his college eligibility!"

The decision was Michael's, but in any real sense it had been made for him by his coach. The night before Michael Jordan was set to announce it, he went out for dinner with Buzz Peterson. He was still uncertain what the right course was. A press conference was scheduled for the next morning. He left for it early, while Peterson stayed in bed. When he returned, Buzz asked him what he was going to do. "You don't want to know," he answered. "I thought you'd stay," Peterson said, slightly wounded, feeling he was losing a friend and seeing something of his own dream torn apart. "I thought we'd come together and room together and graduate together." But Jordan just shook his head, and Peterson understood that the decision was not really his.

On the day that the Chicago Bulls drafted Michael Jordan of North Carolina as the No. 3 pick in the country, Ron Coley, who had worked for a time as a volunteer at Laney High, called James Jordan. "Move over, Oscar Robertson and Jerry West," he said, "because the greatest guard in basketball history has just been drafted."

The greatest testimonials to Dean Smith were that Jordan left Chapel Hill for the Bulls reluctantly, and that he remained passionately committed to his old school and his old coach. As a pro, he not only wore Carolina shorts under his regular uniform, but also checked in with Smith regularly and considered him, many of their friends thought, a kind of second father. If Jordan took away from Carolina great discipline to go with his natural ability, he also took away something more, a sense of right and wrong and of how you were supposed to behave in life. Several years after he had graduated from Carolina he returned for a pre-season game. He and his friend Fred Whitfield had driven up to Chapel Hill a little late, and the parking lot was full. Whitfield spotted a space near the door for handicapped people and suggested that Jordan use it. "Oh, no, I couldn't do that," he had answered. "If Coach Smith ever knew I had parked in a handicapped zone, he'd make me feel terrible—I wouldn't be able to face him."

Excerpted from Michael Jordan: The Making of a Legend, by David Halberstam, to be published next year by Random House, Inc.; © 1999 by Amateurs Limited.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now